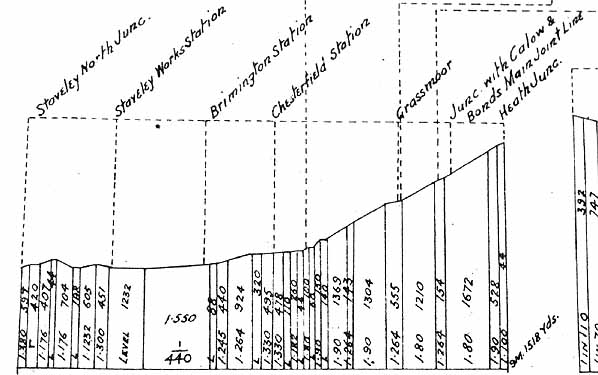

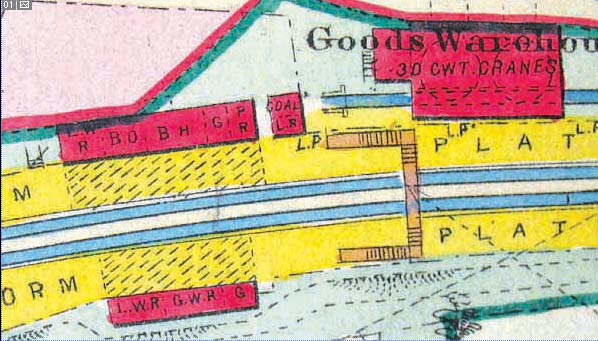

SHEEPBRIDGE AND BRIMINGTON STATION AND CONSTRUCTION OF THE MANCHESTER, SHEFFIELD AND LINCOLNSHIRE RAILWAY THROUGH BRIMINGTON Reproduced from St. Michael & All Saints, Brimington parish magazine Part 1 INTRODUCTION Today still stands the stationmaster’s house along with the somewhat dilapidated ‘up’ platform buildings (in railway parlance the ‘up’ line was always that to London). Once these were linked by a footbridge to another wooden structure on the down platform. There was also a signal box, goods shed, yard and even cattle docks. Opened on what was originally a branch into Chesterfield from Staveley Town station at Lowgates, the line eventually formed a loop off what were termed the ‘Derbyshire lines’ of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway. In this series of articles we will look at the history not just of the station, but also of the line, its construction, traffic along it, and its ultimate demise in 1963. We will also explore the route through Brimington, some of which can still be traced and indeed walked as the ‘Blue Bank Loop’. BACKGROUND The Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway was a regional company. As the Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne and Manchester it had constructed a northern cross-country line from Manchester to Sheffield, opening fully in December 1845. This included the notorious Woodhead tunnel. By the summer of 1846 the Company had absorbed three other companies to become the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS & LR). At this time construction was taking place on what would eventually form a route from Sheffield to Grimsby, together with a dock at that place. The network was opened in 1849, with the docks opening in 1852. The MS & LR’s later expansionist tendencies were undoubtedly mainly due to the influence of Sir Edward Watkin, who had many railway interests. Under his leadership the Company, though sometimes in financial straits, continued to expand. Watkin, who became Chairman of the MS & LR in January1864 , had a dream of a line to London. He was no doubt hoping to replicate the Midland Railway’s and others successful passenger and the particularly lucrative coal traffic to the capital. THE 'DERBYSHIRE LINES' An answer was found at least partially found in what became known as the ‘Derbyshire lines’. This was the culmination of a number of schemes which had probably started in the mid 1840s but gained renewed impetus in the 1870s. Some of these schemes would have seen the Chesterfield Canal filled in and replaced by a railway. The Derbyshire lines proved to be the start of what has been branded as ‘the last main line’ to London. The gaining of parliamentary approval proved to be somewhat complicated, but a Bill seeking construction was eventually passed in July 1889. A peel of bells at Chesterfield Parish Church had been rung when the Bill was carried through the Commons. Even after gaining parliamentary approval, there were some in the district that thought the line would never be built. There had also been some dissent amongst shareholders before the Bill was proposed and it was publicly acknowledged that at one time, despite pressure from interested local parties, the directors did not want a line either. On more than one occasion the drive of the Staveley Coal and Iron Company’s Charles Markham, in getting the line, is acknowledged. As part of a number of gatherings in the district, Brimington added its support for the Bill at a meeting held in the National School on Tuesday 5 February 1889. The National School is now demolished, but was situated on Church Street, opposite the Parish Church. Here a large attendance had heard how the railway would benefit the parish. Construction would aid employment with increased spending power benefiting local businesses. The coalfield would be opened up, with the Midland Railway’s virtual monopoly broken. With an eye on village coffers, the benefits of railways being large ratepayers were aired. As sanitary and other improvements were needed the parish ‘…could do with two or three large ratepayers…’ Brimington would gain a railway station at Wheeldon Mill, though some of those present thought it would be better at ‘Cow Hill’, among other places. Perhaps tactfully, discussion of this subject was postponed ‘…to a future meeting.’ The ceremonial turning the first sod of the Derbyshire lines was performed by the Earl Manvers at Beighton, on the 7 February 1890. Amongst the many dignitaries present was ‘John Lingard (Brimington)’. Lingard was Chairman of both the School and Burial Boards. He had described himself as ‘churchman’ when offering himself for re-election to the former body in 1888. It was Lingard who had appeared at the House of Commons Committee hearing into the MS & LR bill in May 1889. Here he had described himself as a ‘farmer at Brimington, and member of the Chesterfield Board of Guardians.’ He also attended the Rural Sanitary Authority. Lingard had proposed the motion passed at the February 1889 Brimington meeting called to express support for the railway. Part 2 CONSTRUCTION & THE ROUTE THROUGH BRIMINGTON CONSTRUCTION Logan and Hemmingway’s contract was let in January 1890. They agreed to complete the work in 18 months. The firm were experienced contractors, who had undertaken other work for the MS & LR. Partner C R Hemingway recalled that the ‘…Chesterfield Line was a big problem….we began with it from Beighton to Staveley Town, and from there due south to Heath, some six miles. There were many difficulties on the way, three railways to cross, over and under, a timber viaduct, and three canals to cross with temporary bridges. This all took time but by the end of the first twelve months we had all coupled up and were able to have the job fully going with some 30 locomotives, 10 steam navvies, and the necessary complement of plant and men.’ The references to ‘coupling up’ refers to the temporary railway line laid to facilitate construction. There were no great encampments for the navvies who worked on the construction. Workers on the contract boarded or lodged along the route. This happened in Brimington, where in May 1890, the Derbyshire Times reported that, ‘A number of houses at Wheeldon Mill, which have been empty for a long time, have been taken, and are occupied by the navvies, but when the “overland route” is through there is no doubt that a great many will live in Chesterfield.’ J.H. Baker, licensee of the New Inn at the time (later the Great Central Hotel and now The Mill) apparently had ‘…many interesting recollections of the exciting times of that period…’ The Railway Company, incidentally, did not own this public house. ‘Mails’ were run from Sheffield and Chesterfield to bring in workers from along the route. These mails called at local points along the way, first using the temporary line (the ‘overland route’) and later using the permanent way. Local people, including boys, were also employed. A navvy mission room was erected on ‘Brewery Meadows’ at Chesterfield in the autumn of 1890 to cater for the ‘large number’ of men then employed on the construction. Brewery Meadows is situated near the site of the former Trebor Works (itself once a brewery - hence the name). Reviewing work in early May 1890 , the Derbyshire Times found that a mere two months after the turning of the first sod at Beighton, Logan and Hemmingway were ‘pushing ahead’ with the work. Amongst work in progress it was noted that land at Chesterfield was in the contractor’s hands; the temporary line was under construction; six locomotives were at work and an American built steam navvy had recently been started, for the first time, about a mile from Beighton. A telephone network was in operation for about two-thirds of the line, with offices erected near the Sitwell Arms at Eckington, at Staveley and soon to be opened in Chesterfield. At Staveley a large part of a ‘cinder tip’ at the works was already being excavated for an embankment, with men at work in ‘all the cuttings on the route.’ Not surprisingly the construction activities provided quite a spectacle. As previously mentioned, the Chesterfield line was merely a branch. Naturally, this caused some disappointment in the town, which was rectified by the MS & LR pursuing another Bill for extension of the line through Chesterfield to Heath, which became an Act in July 1890. Work commenced on this new section, of some 4¾ miles, before construction on the original line was finished. This included the Chesterfield Tunnel upon which work started on the 1 October 1891. Logan and Hemmingway also constructed this line and ultimately went on to build the London extension of the MS & LR. THE LINE THROUGH BRIMINGTON The line branched off the main line at Staveley Town, heading towards Staveley Works, where a station was established at the bottom of Private Drive, on an embankment, the remnants of which can still be seen. The Chesterfield Canal, which was owned by the MS & LR , was extensively diverted in this area, with a new lock created. Parts of a large cinder tip, to the west of the station site, were removed to make way for the works, the material being used for embankments. Eight pairs of semi-detached ‘Railway Cottages’ were built in the area - these still survive at the north-western end of Station Road, Hollingwood. Parts of the cinder tip (we would now call this furnace slag) remained until comparatively recently at the bottom of the New Brimington area. In 1898 the tip was served by a small branch from sidings, which started immediately west of Staveley Works station. These sidings were created to tap into the business at Staveley Works. The line then entered Brimington - the parish boundary crossing the west end of the extensive sidings, near to the old Hounsfield canal bridge. There was a signal box at the end of the sidings, which extended towards where Bilby Lane crosses the line. The ‘box this must have been abolished fairly early on. It is shown on the second edition Ordnance Survey map of 1898, but not twenty years later. During this time points and crossovers, allowing access to the sidings at their westerly end from the up and down lines, had been removed, along with a cross-over from up to down lines. Presumably this was as an economy, with the sidings able to be controlled from the ‘box at Staveley Works station. Bilby Lane was next approached. This bridge still stands, though is somewhat marooned. The slight cutting in which the double track railway once ran is now filled in . The line ran to Blue Bank Lock where it started to turn in a southerly direction. From this point it is possible to walk the route of the line to Newbridge Lane. Just beyond Blue Bank lock the canal was straitened out for a short stretch to allow the railway to pass. The line skirted the North Midland Railway’s original 1840 line to Rotherham, which is still open, before emerging from the Blue Bank area. Here another stretch of the canal was straightened to allow passage of the line. Heading almost due south, the line went under a raised Newbridge Lane, towards Station Road, the river Rother between these two points being straightened. Thence under Station Road (which was raised on an embankment to facilitate the line’s construction) to the railway station. We are fortunate in that construction of the line was extensively covered in contemporary newspapers. The Derbyshire Chronicle and the Derbyshire Times (there were two Chesterfield based newspapers at the time) along with other district newspapers reported fairly regularly on events on and progress of the line. At Brimington the Derbyshire Times reported in May 1890 that ‘…pile engines are at work preparing for the “overland route” over two streams’. It also noted that the canal was to be diverted. During construction, newspapers made a number of ‘journeys’ over the line. These make fascinating reading, pointing out work in progress, methods of working and, in some cases, now disappeared landmarks encountered on the way. The author hopes to prepare an article in due course reproducing these. The newspaper ‘journeys’ describe the line as it runs through Brimington. The first appears to have been made in the autumn of 1890, when the Derbyshire Times reproduces an article in its edition of Saturday 18th October. This had originally appeared in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph a few days earlier: ‘…Near the quaint village of Brimington, where there will probably be a station, the contractors found themselves between “the devil and the deep blue sea.” They have the rival road on one side, and the canal on the other. They have got to get between. They cannot move the Midland. There is nothing else for it - the canal must shift again. Those stakes in the water indicate what the waterway has to surrender: on the other side the stream is dammed back until the bed can be widened. And thus the masterful railway moves on relentlessly as Fate…’ The ‘rival road’ is the North Midland Railway’s 1840 ‘old road’ to Barrow Hill and Rotherham, still in use today. The canal diversion was that at Blue Bank. Certainty less glamorous than the picturesque language of the journey, was a report in the same Saturday edition of the Derbyshire Times. At Blue Bank, only the previous Wednesday, 13 year-old Lawrence Henry Taylor , employed ‘…to grease the axles of the tip wagons…’ used in construction works, was crushed between the buffers of two of them in a train being driven by William Wood, of Industry Yard, Queen’s Street, Chesterfield. The lad, who had only started work at the railway on the Monday, was found alive, but unconscious. Immediately put on the engine, which was then run to Chesterfield, he was still alive on arrival there, but died on the way to Chesterfield Hospital. The week previously another boy of the same age, Arthur Roberts of Calow, had died in a similar accident at Sutton Wood. At the inquest into Taylor’s death coroner, C.G. Busby, criticised contractors Logan and Hemmingway for sending no representative, commenting ‘…it seemed a great pity that such young boys should be employed to do such dangerous work.’ Amongst the jurors one remarked that there seemed to be insufficient supervision over the lads employed. Wood reported that he had five boys under him, ‘…the youngest appeared to be about 14, and the eldest 17.’ Sergeant Oliver is reported as commenting that, ‘…there appeared to be a great many boys employed on the railway. It appeared to be done for cheapness.’ The Coroner was reported as intimating that some form of recommendation should be sent to Logan and Hemmingway about employing young lads. A verdict of accidental death was recorded. Today, as we pass along this part of the abandoned railway, now forming part of the ‘Blue Bank Loop’ walk and cycleway, it is easy to forget the sweat, toil and real danger experienced by workers on the line. Part 3 - THE ROUTE - THROUGH BRIMINGTON TO THE STATION The Sheffield Telegraph’s October 1890 journey over the route, discussed in part two, was undertaken by three men guided by Mr Logan (of Logan and Hemmingway, the contractors) and his manager a Mr F Collins. The next month a greater audience was present as ‘a party of gentlemen’ including the Mayor of Chesterfield, councilors and other local worthies were treated to a run along the line. Like the earlier visit, the route was traversed using a mixture of the completed line and the contractor’s temporary line. The Derbyshire Courier was represented, reporting the full journey. Its Brimington observations were; ‘…the line [from Chesterfield] goes on to Wheeldon Mill, where the river has been diverted, and about a quarter of a mile further on has to pass between the Midland line and the canal. To enable this to be done a further diversion of the latter has to be made - near the Blue bank wood opposite which Crookes, a Chesterfield butcher, was supposed a few years ago, to have been murdered. Thence the line takes a direct course to Staveley works, where another diversion of the canal has to be made, and where the large cinder tip is being slowly but surely reduced.’ The Crookes reference is to that of the murder of Cuthorpe butcher, Herbert Crookes in March 1884. His assailants were never found. The Derbyshire Times was also present, reproducing its recollections a week later than its Courier rival. This account adds little to our knowledge of work at Brimington, though it does report that J Lingard, as we saw in part one, perhaps Brimington’s leading proponent of the line, was one of the party. By September 1891 construction had rapidly advanced, as the Derbyshire Courier reports in its second journey along the line, this time from the Staveley direction: ‘…[we] come upon Staveley furnaces, and see the lock that is being constructed in connection with the diversion of the canal to this side of the works, and notice its newly–marked course. The sub-way at the Staveley station already bears the line upon it, and will be ready long before the station is opened. Here the sidings branch out - there are four sets of lines, and will probably be more, for the use of mineral traffic. We next notice another piece of diverted canal, to accommodate which a part of the hill was removed. Brimington Station is next reached, and we see that the old road to Newbold has had to take a newer straighter course. The platforms and the “skeleton” of the station offices which are to be of wood are already up together with the signal box. The signal rods, wires, and posts are fixed in position between the Brimington station and the Midland Masbro’ branch, and gives the line a finished appearance...’ The old road to Newbold is the present-day Station Road, under which the railway ran. Here, as previously described, the road was raised and a bridge inserted. This bridge still survives, though filled in. All the bridges constructed by the MS & LR in the area still survive, including those built to accommodate diversion of the river Rother. There are distinctive differences in these structures. For example, Newbridge Lane shares with Bilby Lane in having an iron girder bridge, whilst that taking Station Road over the railway appears to be brick at road level, with stone copings, built on top of iron girders. A brick-yard for the works was established at Staveley and was certainly operating in November 1890. Bridges in the area generally use distinctive blue engineering bricks, usually a product of Staffordshire. Examination, however, of some of the remaining structures does reveal distinct differences. Redder bricks (with blue brick embellishments) are evident on the Railway Cottages at Hollingwood and on the stationmaster’s house at Wheeldon Mill. Some of the blue engineering bricks used on the bridges have a redder hue than others. In some structures it is clear that red bricks have been faced using blue engineering bricks. The colour of the bricks is generally dependent on the type of clay and the firing techniques used. It is possible, therefore, that Staveley made the red bricks with the blue bricks imported. The railway removed most of the remnants of a water mill, slightly to the north of the present car park, situated adjacent to the canal, opposite the ‘Mill’ public house. In this area it is still possible to trace parts of what was probably the tail-race. Advertised in 1789 as having ‘two water wheels and five pairs of stones - apply Joshua Wheeldon’, the mill is later shown for sale in 1884 with four pairs of stones and a bakehouse . Interestingly, the property may also have been involved in a probably short-lived attempt to produce bone china in Chesterfield. It was advertised in 1803 for sale as ‘…dwelling house, stable, water corn mill and flint mill called Wheeldon’s Mill…with close of land called the Holme of ½ acre.’ Flint grinding produces chert, an important constituent of bone china. Plans produced showing land to be acquired for the new railway, prepared for the 1887- 88 Parliamentary session, show the mill as unoccupied by this time. Presumably the attempted sale in 1884 had failed as George Dawes is noted as the owner - he is shown as the miller in 1881 . A few of the buildings are shown as surviving on the 1898 large scale Ordnance Survey map, though the water source had disappeared as the MS & LR’s diversion of the Rother had removed it. The name ‘Station Road’ almost certainly dates from the parish council’s decision to name the streets in 1902. In 1901 the stationmaster’s house is described as in the Wheeldon Mill area. The double tracked line now passed under the road. The station following from the road bridge, infilled by the British Rail Property Board after they gained permission in February 1980. Approached from Station Road, just after the canal bridge, it comprised platform buildings and a goods yard, with shed, 10-ton crane, cattle docks and signal box, complete with stationmaster’s house. The railway already possessed some land in this area due to its ownership of the Chesterfield Canal. By 1827 the MS & LR had a ‘coal wharf’, wharf, wharf house and stables established on the canal side. The wharf, wharf house and stable buildings comprised a joined block. This block appears not to have disappeared during construction of the line. Indeed the properties were probably not demolished until sometime between 1921 and 1938. Part of this group is illustrated on the well-known Nadin postcard of about 1908, latterly published in 1995. Examination of various large-scale Ordnance Survey maps again allows some reconstruction of what was a fairly simple station layout. On the approach road, almost immediately at the entrance off Station Road, backing on to the former canal wharf, were situated a weigh machine and small office, now demolished. Passing these, the yard opened out, with the stationmaster’s house (complete with garden) to the west. Two cattle pens followed shortly, to the east. Sidings ran in from the main line into the yard. A large wooden goods warehouse, towards the end of the yard, survived until November 2001, when it was accidentally burnt down. The station access veered from the approach road, just before the stationmaster’s house. There were wooden buildings on both the down and up platforms, though the latter was the main accommodation, complete with booking office. To the south of the main up building stood (indeed still stands) a smaller building. The platform buildings had gable-ended, glazed, ridge and furrow canopies. These were cantilevered on a central row of columns, the platform ends having decorative valances. These, like some other Derbyshire line canopies, were beveled off and partially re-roofed with asbestos corrugated sheets sometime after the grouping of railways in 1923. Apparently the outer ends (i.e. track side) of the canopies, which were unsupported, showed a propensity to pivot on the columns and so pull away from the building. There were the usual toilets and waiting rooms. The up and down platform were linked by a lattice iron footbridge. This design of wooden buildings is typical of the Derbyshire line stations. Gordon Biddle in his Victorian Railway Stations book has described these buildings as ‘…some of the best wooden stations in England…’ To the south end of the station, just off the up platform was the small wooden signal box, which would have controlled points and signalling into the goods yard and on the main line. There were crossovers just in front of the ‘box joining the up to down lines, connecting into the goods yard from the down line. There were a couple of head-shunts to the south of the up line to enable access into the goods yard, particularly from the down line. Though the stationmaster’s house remains, perhaps more unlikely survivors, given that the station closed over fifty years ago, are the majority of the up platform buildings. These are still just recognisable as a typical Derbyshire line station building - complete with a few surviving ornamental terracota ridge tiles. The platform awnings and the down side buildings were removed before July 1959. Shortly after passing through the station, the parish boundary runs a short distance alongside the former track (with the railway being inside the boundary). A little further the railway burrowed under the old North Midland Railway (NMR), alongside the canal, passing from the parish just beyond this bridge. In July 1890 contractors were actively involved in taking the MS & LR line under the old NMR (by this time the Midland Railway). The Derbyshire Courier found ‘…the line above being supported by huge pieces of timber. The men are busily engaged in widening and deepening the passage, adding more timber as they proceed. Meanwhile trains pass over the place at very much reduced speed.’ Beyond, outside the parish boundary, the line again ran under the railway, this time the direct line to Sheffield from Chesterfield. This area was traditionally known as ‘Three Bridges’. There were three bridges under the railway; the Chesterfield Canal, followed by the MS & LR loop then by another bridge which took the Midland Railway’s ‘Canal branch’ to Sheepbridge works and beyond. The Canal branch connected to the south-easterly end of the MS & LR’s Sheepbridge sidings. These acted as exchange sidings between the Midland and the MS & LR and were laid out in the area between ‘Three Bridges’ and Lockoford Lane. The ‘Canal Branch’ connected with the MR’s Sheepbridge railways at ‘Dunston and Barlow Sidings’ - a little to the north of the removed rail bridge on Brimington Road, near Pottery Lane. This removed bridge carried the MR’s line out to Sheepbridge and then to Monkwood and Nesfield, near Barlow, via a road crossing at the bottom of Whittington Hill. Today, when walking this area, very little evidence of the MS & LR’s passage remains, though it is still possible to trace some remnants of bridge abutments. The hectic activity of the 1890s construction is forgotten, along with the passage of numerous freight and passenger trains thereafter. PART 4 OPENING There was little in the way of celebrations. At Chesterfield the opening seems to have been over shadowed by the cutting of the first sod of the Lancashire, Derbyshire and East Coast Railway, scheduled for the 7 June. This line had its Chesterfield station next to the Portland Hotel, in the town centre. So enthused were the town council by this event that they had were requesting inhabitants of the town to decorate their shops and houses to celebrate. Despite the low-key opening Vernon Brelsford, in his History of Brimington… (1937), was able to recollect his journey on the opening day, when he ‘…travelled with scores of other Brimington residents by the first passenger train, which ran from Brimington to Chesterfield.’ According to Charles Clinker in his Register of Closed Passenger Stations… the station was originally opened as plain Brimington, being renamed Sheepbridge and Brimington in June 1951. This however seems strange as, for example, a 1903 and 1949 official timetable and a 1911 handbill clearly state ‘Sheepbridge and Brimington’. Conversely, a ticket issued in 1955, reproduced in this article, bears the name ‘Brimington’! Official correspondence over closure in the mid 1950s refers to the Station as simply Brimington. Vernon Brelsford clearly states, in the late 1930s, that the station is named ‘Sheepbridge and Brimington’. A photograph of the signal box, probably in LNER days, shows part of a station name-board that appears to be lettered ‘Sheepbridge and Brimington.’ The signal box looks as though it has fairly new ‘Brimington’ name-board in the Gill Sans lettering style used by the LNER, perhaps replacing a longer title. A 1948 picture of the station shows a nameboard clearly labeled ‘Sheepbridge and Brimington’. Whatever the arguments over its name, the station’s situation, a heavy walk of over half a mile uphill to the village centre, or a fair distance from Whittington Moor, was probably the reason for its relative lack of business. Despite this, the author has met at least one resident who, in his earlier years, would much sooner walk to the station and catch a train to Chesterfield than brave what was at one time a lonely walk into Chesterfield via Chesterfield and Brimington Roads. By 1937 Vernon Brelsford is quite clear that both Sheepbridge and Brimington and Staveley Works stations ‘…are not used much locally, except as a means of linking up with more important stations for long railway journeys.’ PASSENGER SERVICES On opening in 1892 the passenger service from Chesterfield to Sheffield consisted of ‘thirteen trains up and down a day…’ with special ‘market trains’ on Saturdays and four trains each way on Sundays. Presumably all these trains called at Sheepbridge and Brimington. The line from Chesterfield to Sheffield had stations described as ‘Sheffield, Darnall, Woodhouse Junction, Beighton, Killamarsh, Eckington and Renishaw, Staveley Town, Staveley Works, Sheepbridge and Brimington and Chesterfield.’ Of these only Darnall and Woodhouse remain open, the Sheffield station being the now closed and demolished Victoria. These two stations were on the original line to Grimsby. The Derbyshire Times bemoaned that ‘all the trains are slow, the time occupied being forty-five minutes,’ presumably by the journey from Chesterfield to Sheffield. The newspaper ‘…regretted that the Company have not seen their way to put on one or two expresses, but probably this will have to wait until their through connection to Nottingham is completed…’ These expresses, had they run, would probably not have called at Sheepbridge and Brimington. The extension of the branch, through the Chesterfield Tunnel to a junction at Heath with the line that ran to Nottingham, opened in July 1893. This brought a change to services. Fifteen trains, plus one Saturdays only, were running from Sheffield to Chesterfield, with seven running forward to Nottingham. Seven of the fourteen Chesterfield to Sheffield trains started from Nottingham. All these stopped at Sheepbridge and Brimington. On Sundays the station received five trains from Sheffield, of which three went forward to Nottingham. Towards Sheffield five trains called, three of which had originated from Nottingham. The expected Chesterfield to Sheffield ‘fast trains’ had not materialised. In March 1899 the Company opened its London extension, with a brand new terminus at Marylebone. In anticipation of this opening the M.S. & L.R renamed itself the Great Central Railway on 1 August 1897. This now meant that Sheepbridge and Brimington, like Chesterfield, was in a loop off the main line from Sheffield Victoria to London, via Nottingham and Leicester. Perhaps because of this position Chesterfield had very little in the way of the hoped for expresses. By late summer 1903, thirteen trains in the down (or Sheffield direction) served Sheepbridge and Brimington station. Three appeared to start at Leicester, seven from Nottingham and three from Chesterfield. They ran as local stopping trains to Sheffield Victoria. There was one additional Saturday only train. Six trains served the station on Sundays. In the up direction the station received thirteen trains, with two additional on Saturdays and a total of seven on Sundays. A weekday through train from Leicester to Cleethorpes appeared to be the only train on the loop that did not stop at Sheepbridge and Brimington. The service, though, was rather irregular, presumably catering for work and shopping travel. For example, weekdays the first down train (Sheffield direction) departed at 6.25 am, followed by a second at 7.32 am, then there was a gap until the next departure at 10.21am. This, though, was better than in August 1893 when the first departure was 7.51. The final up train was the 10.43 pm to Sheffield, where it would arrive at 11.23 pm, having started its journey from Leicester at 8.15 pm. Chesterfield bound the final departure was the 11.51 pm, terminating in the town at 11.55 pm, thus giving the usual time between these two points of four minutes. A return to London in 1903 cost 38 shillings and 10d (just under £2) first class. For third class it was 24 shillings 5d (just over £1.20) - there was no second class. Horses were 37s each, 51s for a carriage. Not that there were any direct trains to London, of course. There was, however, a weekdays express passenger Manchester to London by 1915, which alone served Chesterfield on the loop. This departed 5.20pm, arriving Marlyebone at 8.50pm. The railways were regrouped in 1923. Four big companies were created out of a multiplicity of major and minor players. The Great Central Railway became a constituent of the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER). By 1925, the Sunday service was much reduced; to just two trains each way on the loop, both of which stopped at Sheepbridge and Brimington. In the up and down direction there were twelve weekday departures each way. There were two additional services on Saturdays. Perhaps the beginning of a reduction in services is indicated by two Saturday only services in the down direction, which did not call at the station, along with a weekday service. The first weekday down train departed (ex 5.45 am from Chesterfield) at 5.49am, arriving 6.27am at Sheffield Victoria, having deposited its customers on Staveley Works station at 5.54 am, allowing a mere six minutes for Staveley Company employees to get to their work-place for a 6 am start. How many actually used this service is not known. This train was followed by departures at 7.36 am and 8.28 am, then a gap to 10.16 am. The final train was the 11.12 pm Saturdays only departure, otherwise it was 10.19pm. Again the service was somewhat irregular. Late mornings and afternoons there were gaps of some two hours. Up side weekday departures showed a generally similar pattern, with the first departure at 5.52 am, arriving Chesterfield at 5.56 am. This train had started from Sheffield Victoria at 5.05 am, terminating at Nottingham Victoria at 7.03. Further departures followed at 6.57 am, 8.37 and then 10.34. Apart from Saturdays, when there was one additional train, the service was about every two hours until the late afternoon, when it went roughly hourly. The last departure was 11.12 pm, proceeded by one at 9.52 pm. A big problem for passenger traffic on the loop, was that the nearby Midland line (London Midland and Scottish Railway after 1923), also tapped similar markets. Due to its position, next to the railway bridge at the bottom of Whittington hill, the LMSR’s station at Sheepbridge potentially served more people than Sheepbridge and Brimington. Next along the LMSR was Whittington, not so well placed in relation to the village it served, but the station at Barrow Hill was nearer the settlement than the LNER’s Staveley Works. The LNER’s Staveley Central station, at Lowgates, was better placed than the LMSR’s Staveley Town. For comparison, in these generally depressed times, ‘Barrowhill and Staveley Works’ LMSR station received fifteen weekday trains (four additional on Saturdays), with two Sunday trains, from Chesterfield. This compared with Sheepbridge and Brimington’s twelve. Burgeoning bus services, particularly from the 1920s onwards created further, perhaps more, intense competition. It should be remembered that East Midland Motor Services, who ran extensive services in the area, were jointly owned by both the LNER and LMSR from 1929. The company’s most frequent service from Chesterfield in 1930 was to Brimington and Barrow Hill. There were other operators, notably Chesterfield Corporation and more locally Brimington based Doughty’s. Second largest of the ‘Big Four’, though well managed, the LNER had the weakest financial position. This, coupled with the Chesterfield Loop being at best a secondary line on the LNER’s second route to London (their principle ‘East Coast’ line being into Kings Cross), would have meant finances were tight. It was during LNER ownership that the platform canopies were cut back. Some work was, however, undertaken on the main line, with substantial stretches re-laid in 1933 . But published photographs of Chesterfield Central station in 1936, show a generally poor condition. Maintenance of Sheepbridge and Brimington’s buildings were therefore less then ideal. September 1949 finds Sheepbridge and Brimington with a further reduced service. There were no services on Sunday, though there were four serving Chesterfield Central. Weekdays saw nine trains in both up and down directions. On weekdays, Sheepbridge and Brimington received its first train from the Chesterfield direction (departed the town 5.40 am) at 5.44 am, arriving Staveley Works at 5.49, giving a little more time for those employed at the complex to arrive on site. The next train followed an hour later, with a third at 7.13am, then a gap to 9.34 am, 12.17 pm, 1.24 pm, 4.32 pm, 5.26 pm, with the last train at 8.29 pm. Two trains were retimed on Saturdays. In the up direction the first arrival was from Staveley Town (departed 6.10 am) at 6.20 am, which ran to Chesterfield arriving at 6.24 am. This was followed at 6.57, 8.37, 10.03, 11.55, 3.40 pm, 4.53, 6.29, with the last train at 8.07 pm. The general pattern of services on the loop at this time appears to have been Sheffield Victoria to Nottingham Victoria ‘all stations’ trains. The stations being Darnall, Woodhouse, Beighton, Killamarsh, Eckington and Renishaw, Staveley Town, Staveley Works, Sheepbridge and Brimington, Chesterfield Central, Heath, Pilsley, Tibshelf Town, Kirkby Bentinck, Hucknall Central, Bullwell Common, perhaps New Basford and into Nottingham Victoria. Grassmoor, the only station from Chesterfield to the loop’s junction with the main line at Heath, had closed in 1940. Of the original Derbyshire lines stations, dating back to the opening of 1892, Beighton, Killamarsh, Eckington and Renishaw, Staveley Works, along with Sheepbridge and Brimington, had all lost their Sunday services by 1949. By this time, however, Chesterfield was served by an express - the 5.33 pm weekday departure to Marylebone from Manchester (London Road, now Piccadilly), complete with restaurant car. A year later Sheepbridge and Brimington received a mere five up and down weekday services. The first service from Sheffield arriving at 6.57 am, then 10.39, 3.40pm, 4.53pm, with the last train at 6.31pm. The down service was equally sparse - 7.13 am, 1.24 pm, 4.32pm, 8.29pm - of these the 4.32pm did not run on Saturdays! Services on the loop were much reduced. The first and last Sheepbridge and Brimington trains were the first and last on the loop. But the restaurant car express serving Chesterfield survived. Fares to Sheffield from both Sheepbridge and Brimington and Staveley Works were 4 shillings and 5d (just over 20p) first class or 2 shillings and 7d third. This might be compared with the 3 shillings and 9d first and 2 shillings and 4d fare from the old Midland station at the bottom of Whittington Moor, which lay on the direct line to Sheffield. The journey from Barrow Hill, via the old Midland Railway’s route cost the same as from Sheepbridge and Brimington and Staveley Works, with six weekday departures to the city. Local services to Sheffield on the old Midland route were withdrawn in January 1952. The station at the bottom of Whittington Moor did not, however, close until 1967. This station was served by local trains on the direct line to Sheffield. Meanwhile Beighton station on the old MS and LR had succumbed on and from the 1 November 1954. In our next part, we will look at excursion and goods traffic from the station, along with its eventual closure. As we will see, a survey taken in 1954 makes pitiful reading. On average only 38 fare-paying passengers had joined trains each day, making closure somewhat inevitable. PART 5 EXCURSION TRAFFIC Therefore, we find Dean and Dawson offering a selection of trips over the MS and LR’s and later the GCR’s lines, even beyond the grouping of 1923. The successor to the GCR, the London and North Eastern, were certainly still advertising Dean and Dawson excursions in 1925. Unfortunately, local newspaper advertising for our already sampled 1903 and 1923 passenger service periods does not appear to be extensive. Presumably, Dean and Dawson relied heavily on what became familiar printed advertising leaflets, which were hung up in booking offices on string, via a punched hole, usually to the top corner. An example of this, from 1911, though reduced in size, accompanies this article. It shows that not only did excursion traffic depart from Sheepbridge and Brimington, but that it also arrived there – on this occasion for the Chesterfield Races. In 1925 the LNER were taking out quite large advertisements to promote their ‘Dean and Dawson’s Summer Holiday Excursions from Chesterfield Central.’ Destinations on eight or 15-day return tickets included western England, south Wales, and even Ireland. London also featured, as did a variety of other destinations. Sheepbridge and Brimington is not mentioned as a departure point. For August bank holiday 1925 day excursions were advertised from Chesterfield Central, though again other stations are not mentioned. By this time Dean and Dawson had an office at 25 Cavendish Street. There were other inducements to travel, including reduced tickets and period returns. According to the Derbyshire Times the LNER later reported a slight decrease in numbers heading to destinations – the most popular being Cleethorpes and the eastern counties. Cleethorpes had featured right at the beginning of the ‘Derbyshire Lines’ incursion into Chesterfield. A cheap excursion to the east coast resort had taken place on the Monday after the line had opened on Saturday 4 June 1892, when over 1,200 people had booked on the train, ‘off the branch.’ Perhaps the onslaught of motorbus and coach excursions had prompted increased newspaper advertising by our 1949 sample period. Despite this competition, there was a regular excursion programme. For example, in January British Railways Eastern Region, was advertising regular Saturday excursions to Sheffield starting from Chesterfield Central and calling at 12.21pm at ‘Sheepbridge (ER)’. For 1 shilling and 9 old pence passengers would arrive at Sheffield Victoria at 1.3pm and could return at 5.45 or 7.20pm. The annual summer shutdown of Chesterfield and district factories and the mass exodus surrounding it is something we perhaps find hard to imagine today. In 1949 it was estimated that 15,000 employees and their families in the district were on holiday. All the large works, except one, and many smaller concerns were closed. These so-called ‘Wakes and Town Holidays’ from Sunday 24 to Friday 29 July, featured cheap tickets from stations including ‘Sheepbridge, Staveley Works and Staveley Town’ to places within a radius of 60 miles. However, there appeared to be no advertised excursions from our station, though the London Midland Region ran a full programme, including departures from ‘Sheepbridge (LMR)’ (the now closed station at the bottom of Whittington Hill) and Whittington itself. The Derbyshire Times on Friday 24 July 1949 reported on the ‘great exodus from Chesterfield’ over the weekend. With soaring temperatures, queues were reported at Chesterfield Midland Station from 10.30pm as people headed towards the coast. A late August newspaper advertisement saw Wheeldon Mill a calling point to Wadsley Bridge for Chesterfield’s match with Sheffield Wednesday on Saturday 3 September. With a fare of 2 shillings the train departed at 1.5pm. Chesterfield lost four goals to two! Belle Vue, a large amusement park and zoo near Ashburys Station on the original MS and LR’s line into Manchester, was a popular destination. Evening trips were scheduled for Saturday 27 August and 3 September. Departing at 4.33pm, there was an option to return from Manchester at 9.50pm (for 4 shillings and 9d (old pence)) and Ashburys (4s 9d) at 9.56pm. On Saturday 10 September, 5s 11d would have ensured travel to Doncaster for the St Ledger race meeting. The following Saturday Blackpool featured, for 10s 6d, departing at 1.3pm, arriving at 4.53pm, with an advertised return (presumably a departure) at 1.5am on the Sunday morning. Perhaps a rather unusual departure was that at 10.25am on Sunday 18 September for Grimsby or Cleethorpes, particularly as by 1949 there were no scheduled Sunday services at the station. The previous Sunday’s excursion on the loop, to the same place, had not served Wheeldon Mill. Saturday 1 October saw another evening excursion to Belle Vue. The same week saw excursions to Nottingham Races for 5s 7d. The Goose Fair excursion the following Saturday did not call, though one to Blackpool did. During this period Eastern Region advertising refers to the station as ‘Sheepbridge (ER)’ whilst a London Midland Region advertisement refers to ‘Sheepbridge and B’. Looking at this brief sample of excursion traffic, it is clear that the station enjoyed a fairly good service, at varying periods, with some staple destinations. How many Brimington people used these facilities is not clear. It is also not entirely clear whether any private excursions or ‘guaranteed excursions’ used the station, though there is some verbal evidence that at least one trip was run from there by Brimington Club. Did the station’s remoteness from the village perhaps stop local organisations using the station as a start for their annual trip? Readers with any knowledge of this type of activity are invited to contact the author. PART 6 Access to working timetables (WTTs) gives some insight into traffic patterns other than those available in passenger timetables. They were regularly published by each railway company, but were for the ‘guidance of the company’s servants only’. WTTs showed every booked train – passenger, goods, coal, cattle, etc. along with their times along a given route. They also contained other information, such as signal box opening and closing times. Normally WTTs were destroyed when the next version appeared. This could be a matter of months as the company adjusted to new traffic opportunities or contractions. The author has obtained access to a number of WTTs, enabling a better picture of services at Sheepbridge and Brimington to emerge, albeit limited to the WTT sets available. RUNNING POWERS The London and North Western Railway Company (more famous for its ‘West Coast’ route from London Euston to Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester and beyond) and the Great Northern Railway both enjoyed such powers. These powers were welcomed locally, as they were seen as offering yet more competition to the Midland Railway. A GCR WTT from July 1915 shows a number LNWR goods and coal train examples, including at least one weekday service, which traversed the loop on its journey from Colwich to Woodburn Junction near Sheffield. This was booked to stop at ‘Sheepbridge’ as required. Unfortunately, we do not know if the LNWR directly served the station, as no indication is given as to whether the ‘booked’ calling point is the exchange sidings or station, or indeed both. GNR trains were more limited, none were booked to travel the loop. Presumably the expected traffic did not justify it. The GCR had running powers over some LNWR and GNR lines. In 1907 it was reported that the GCR had 169 miles of such powers over the GNR. The GCR’s Nottingham Victoria station was a joint one with the GNR. The Derbyshire Lines also joined with the GNR’s at Annesley. Relationships between the two companies were generally friendly. An amalgamation, which later failed, was being pursued in 1907. 'WORKMEN'S' SERVICES A weekday 5.20am service started at Sheepbridge and ran, calling all stations, to Heath, followed closely by a second which had started at Staveley Town 5.30am; 5.34am at Sheepbridge, all stations to Grassmoor, thence to a platform at Bonds Main Colliery. This train than ran back to Chesterfield, as empty stock (i.e not carrying passengers) ‘for cleaning purposes’. There was a Saturday only mid-day departure from Sheepbridge all stations to Heath . A Saturdays excepted Sheepbridge all stations to Heath, departed at 1.40pm again running to Bonds Main Colliery (there was a further service to Bonds Main from Chesterfield only, at 2.35pm). Later a further Saturdays excepted workmen’s Staveley Town (dep. 4.40pm) all stations to Chesterfield served Sheepbridge, with another Saturdays excepted Sheepbridge to Heath, again via the Bonds Main platform, departing at 8.45pm. In the other direction workmen’s services on the loop commenced with the 5.25am from Chesterfield, with an all stations to Staveley. This would have enabled Staveley Works employees to have alighted 5.35am at their station. Bonds Main was served at 6.25am with the 6.20am departure from Heath, all stations to Sheepbridge, where it arrived at 6.41, giving a respectable journey time of under 20 minutes. Saturdays saw another Bonds Main service depart for Staveley Town at 1.10pm, followed by a Heath (depart 1.30pm) to Sheepbridge. There were other late afternoon services from Bonds Main and Heath and a late night Saturdays excepted service from Heath and Bonds Main. Other workmen’s trains operated on the loop which did not serve either Chesterfield or Sheepbridge, such as Heath to Tibshelf Town. 1915 was, of course, a war year. It might be expected that traffic should be higher than normal during this period. Without, however, the benefit of being able to examine other WTTs of the immediate pre and post-war years it is not known if the workmen’s trains were typical. These trains, on the loop at least, were probably mainly for the benefit of miners. The Bonds Main traffic is of particular interest. The GCR had opened a short branch to this colliery from its loop on the 13 May 1901 but had established a ‘colliers’ station’ earlier – opening on 13 March 1900. The Midland also had a mineral branch to Bonds Main. Bonds Main colliery was developed from 1895 by the Staveley Company . Situated a little to the north east of Temple Normanton, the mine closed in 1949. Undoubtedly, Brimington people worked there. In 1899, for example, a Brimington boy, Bert Brown, died from injuries when he was crushed by a runaway tub in the mine. The site of Bonds Main disappeared following opencasting in the 1960s and early 1970s, with the A617 Chesterfield to M1 dual carriageway cutting across its site. Without further research it is not known when workmen’s trains disappeared on the GCR. By 1949 they are certainly not separately designated on the successor company’s WTT. Bonds Main Colliers’ platforms were disused at least by February 1929. Just like the numerous special bus services run by Chesterfield Corporation’s Transport Department, local work services have disappeared into history. We might, however, picture colliers making their early morning departure or late evening return from and to a dimly lit Sheepbridge and Brimington station. Blackened by their day’s work, in times before pithead baths, when a trek home would be followed by a strip-down wash or tin bath. FRFEIGHT SERVICES The 25-inch Ordnance Survey map of 1898 shows the station complete with goods shed, cattle pens, goods yard and weighbridge. The level of use that these facilities saw is hard to determine without further research to see if traffic receipts survive. The available WTT for 1915 does not differentiate between the station and the nearby exchange sidings, simply annotating the stop as ‘Sheepbridge’. Therefore it is difficult to say exactly what freight services stopped and shunted at the station. What the WTT does show, however, is that freight traffic was not particularly busy on the loop. Weekdays (excepting Mondays) saw only four booked workings at Sheepbridge in the up (from Staveley) direction, far less than passenger trains. Towards Staveley traffic was busier, with about 14 trains. Not all these services called at Sheepbridge. There would be additional light engine, empty stock working, pilots and diversions off the main line, particularly if traffic was heavy. Of some interest is the 1.15am Mondays excepted ‘Special Express Fruit and Vegetables’ which ran from Banbury to Manchester. This called at Chesterfield (not Sheepbridge) from 5.5am for 15 minutes, reminding us of the days when the only the railways could effect such rapid transfer of perishable goods across the country. In 1925 it is clear that evening newspapers sold by village newsagent Mr Nash, were collected from Sheepbridge and Brimington Station, usually by one of the newspaper delivery boys on a cycle. These were possibly delivered from a stopping passenger train. Livestock was also dealt with. One local butcher, J T Holmes who is first listed in local directories in 1895, would apparently fairly regularly fetch livestock from the station up to a field opposite his slaughterhouse and shop on the corner of Burnell and High Street. There was also at least one delivery dray operating from the station. This was used in the early 20th century Sunday School Union ‘demonstrations’ as a decorated float (it is pictured in this article). What other traffic was consigned locally is not known. Brimington, for example, had numerous brickworks, what if any production left the village and then by rail is, again, not known. Typically coal would be received by rail and dispatched at such stations as Brimington – one of the primary uses for the weighbridge. Although a coal merchant - James Henry Baker - was based on Station Road from some four years from 1904, it is not known if he traded from the station yard. In 1922 Kelly’s Directory of Derbyshire lists a Samuel Haslam as coal merchant on Station Road. Again, the author does not know if he was based in the station yard. Confirmation of any coal merchants operating from the station site pre 1956 would be welcome. Coal and ironstone traffic were clearly one of the main reasons for the ‘Derbyshire Lines’ construction. In 1893 the Derbyshire Times spoke of the MS and LR’s line being ‘one more step towards connecting the great Metropolis with the Midland Coal field…’. Other contemporary descriptions make great play of not just gaining access to Chesterfield but also to the many collieries in the district. The MS and LR itself made great play of the amount of support it had in the area from coal owners. At the turning of the first sod of the ‘Derbyshire Lines’ in February 1890, the company estimated that the coalfield served by the railway produced 17 million tons of coal per year. Connections with ports at Grimsby, Goole and Hull for export were emphasised. Output from Staveley and Sheepbridge ironworks and collieries was highlighted, along with ironstone traffic from the Lincolnshire ironstone fields. This was typically reflected in 1915 services such as, for example, a ‘through mineral’ Frodingham to Sheepbridge and the Staveley Town to Barnetby coal train. In reality traffic on the loop never appears not to have been overly busy, even in 1915, when there were about 18 week-day freight trains passing or booked at Sheepbridge in the up and down directions. The October 1947 WTT shows some 13 week-day freights booked up and down, along the loop, through Brimington. Like 1915 not all stopped at every station or the exchange sidings, or ran every day. They comprised a mixture of mineral, various classes of freight and empty wagons. As in 1915, some light engine movements, pilots and diverted trains would occupy the line. The first week-day freight at the exchange sidings was booked at 7.40pm (from Annesley to Sheffield Bernard Road). Unfortunately the WTT lists freights only at the exchange sidings, so it is not possible to say what stopped at Brimington. However, we do know how long the journey took - nearly 5 hours. Starting Annesley at 5.50am, the train was ‘booked’ Chesterfield 6.41; Sheepbridge exchange sidings 7.40; Staveley Works 8.20; arrived Staveley Town 8.32, departing 9.5; finally arriving Bernard Road at 10.43am. The year before effective closure of the station, in 1954, only about 434 tons of freight was forwarded from the station goods yard. This had consisted of occasional lots of old sleepers and scrap steel, with some 1317 tons received, mainly coal and old sleepers. One freight train called each day. The laborious, slow and labour intensive nature of British Railway’s freight operations were the source of concern for a number of years. There was little scope for the pick-up goods train to compete with the modern road carrier, both in cost and delivery times. These issues were perhaps more radically addressed in the famous Beeching Report of 1963. MOTIVE POWER REQUIREMENTS The MS & LR established a large locomotive depot at Staveley as part of the Derbyshire Lines project. It could hold 60 engines, with two turntables and the usual adjacent facilities for running repairs. This shed, along with that at Neepsend in Sheffield, supplied locomotives for the first section of the new lines. Travelling through Staveley today, passing east over Lowgates Bridge, the MS and LR’s station was located to the left. The main line ran immediately under the bridge, roughly north to south. Looking south the Chesterfield loop diverged from the main line to the west, with the depot a little further south on the east side of the main line. All traces of the depot, closed in 1965, have disappeared. Houses in this area (on Belmont Drive etc.) are amongst the 99 constructed by the MS & LR. Former shed-master ES Beavor gives a good account of Staveley shed in the early 1950s, in his book ‘Steam was my Calling’, This includes an account of the motive power frequently used at the time – mainly ex Great Central types. Indeed, dieselisation appears to have been limited even near to the end of operations in the 1960s. Beavor recalls the Staveley passenger turns as being limited to two stopping services, both to Sheffield Victoria, over the loop; ‘One of them operated a shuttle service thence to Chesterfield, the other from Sheffield to Nottingham and back to Staveley. We had three class C13 4-4-2 tanks [steam engines] to cover these duties.’ It is believed that, certainly latterly, this passenger duty comprised just two coaches. Again, comments on passenger and freight workings along the loop will be gratefully received PART 7 In August 1955 BR wrote to Chesterfield Rural District Council (CRDC) stating that the ‘…small amount of traffic dealt with, including freight, passenger and parcels does not justify the expense involved…’. BR intended to ‘…close the station except for the private sidings and the retention of the facilities for dealing with guaranteed excursions on and from a date to be decided.’ These ‘guaranteed excursions’ were special trains run usually for interest groups such as working men’s clubs, Sunday Schools, etc. These could be run from closed stations, subject to the need and until the station in question became unsuitable. As previously discussed, there is some oral evidence that such trains may have run from Sheepbridge and Brimington, but further confirmation would be welcome. A memorandum, mainly consisting of a traffic survey, accompanied the letter from BR to the CRDC. This found that the service then consisted of five weekday trains in each direction, with seven on Saturdays. During the period of the winter 1954/55 timetable, there had been eight trains to Sheffield (nine on Saturdays), with nine from the city. One freight train called each day. There were no Sunday trains. A census taken during the week ending 18 September 1954 makes pitiful reading. On average 38 fare-paying passengers had joined trains each day, with 26 alighting. On the Saturday 18 had joined with 28 alighting. Railway employees accounted for a further 15 joining, and 14 alighting, per day, with 13 joining and 12 alighting on the Saturday. The memorandum records that only about 434 tons of freight was forwarded from the station goods yard in 1954. This had consisted ‘mainly of occasional lots of old sleepers and scrap steel, whilst about 1317 tons were received there, comprising chiefly coal and old sleepers.’ Closure and withdrawal of goods facilities would ‘enable a net economy of £2950 a year to be obtained after allowing for losses in traffic.’ Alternative bus facilities were good and freight could be dealt with at Sheepbridge station on the Midland line about a mile away. There was ‘no known prospect of any local developments which would materially affect the traffic dealt with at Brimington.’ A few days after receipt of the BR letter , the Transport Users Consultative Committee (TUCC) asked if the CRDC had any objections. In turn, the Rural District Council informed local members of the authority along with Brimington Parish Council. There was no campaign to keep the station open. Newspaper coverage of the closure, such as it was, seemed to spark little or no reaction in Brimington . The parish council raised no objections to the proposal, as facilities would be retained for dealing with guaranteed excursions. They did, however, feel that there should be an ‘assurance that the platforms will be retained.’ Prominent member of both Brimington Parish and Chesterfield Rural District Councils of the time was Walter Everett. An engine driver employed at the former Midland Railway Barrow Hill sheds, it is not recorded what his thoughts were on the closure! The Rural District Council agreed in September to make no objections, supporting the parish council in its view that the platforms should be retained. These views were conveyed to both the railway and the TUCC. Assurances were obtained over retention of the platforms for guaranteed excursions, until ‘costly repairs or renewals’ became due, when the position was to be reviewed. The East Midlands TUCC duly considered the matter. It was decided that the station would close on and from Monday 2nd January 1956. As there were no Sunday services, this meant that the last service to leave Sheepbridge and Brimington Station would have been on the evening of Saturday 31st December 1955. That traffic had been light for some years, has been demonstrated in the steady reduction of timetabled passengers trains. Even in 1947 the station signal box was staffed on a ‘weekdays open as required’ basis. It is not known whom the ‘private sidings’ were intended for, but in any case annotations to the official mileage diagram for the Chesterfield loop in the National Archive indicate that all the station sidings and the signal box were abolished in March 1956. This included the connection to up and down lines between the platform. Whilst services on the loop remained until 1963, so ended some 63 years of passenger traffic at Brimington’s own railway station. SUBSEQUENT USE OF THE SITE The station house was let by the BR to Mr and Mrs Lord, who moved there in February 1956. Apparently, they had been waiting for the former stationmaster to move. They subsequently purchased the house from BR, but later moved. When the rest of the station site was sold off is not known. Particularly from the late 1970s the site deteriorated. There were a number of planning applications for various processes, involving the then site owners – Hopecrete Ltd. By 1971 a concrete works, mainly for the production of paving slabs, was in operation. Outline planning permission was granted to Hopecrete by Chesterfield Rural District Council for a factory and offices on the old station yard site in 1972. In 1980 a temporary five-year planning permission was obtained for infilling land to be used for car parking and storage of building supplies. In 1988 permission was granted for storage of building supplies, subdivision of the site for uses including general industry, sale of coal, logs and building materials and forming a new access from Station Road, beyond the old station yard site. Relationships between the site and the planning authorities has been somewhat fraught in relatively recent times. There was enforcement action for unauthorised coal screening. More controversial was the unauthorised stockpiling of old tyres, which resulted in further planning enforcement and eventual prosecution of the then owners in 1988. A year later a massive fire took place within this tyre dump, when more than 5,000 lorry and tractor tyres were reported as being destroyed. In 1990 further enforcement action followed when residential caravans on the site were removed. By 1991 an application for renewal of the five-year temporary planning permission was refused, it subsequently went to appeal, being allowed, with various conditions. Today the station site remains in a variety of uses. Mainly brieze-block built small industrial units have been built to the side of the old station approach road. The brick-built buffer stops to the former long siding, near where the cattle pens once stood, have been unfilled, with a car-sales standing on their site. The remaining station buildings have been let to a number of tenants, including a transport business. When the author visited this part of the premises recently it was clear that the interior had been gutted some years ago. As previously recounted, the large wooden goods warehouse, survived until November 2001, when it was accidentally burnt down. The distinctive rounded edge platform copings must have been removed in recent times. Two survive as a seat on the canal side paved ‘wharf’ area to the east of the station site. It is believed that others may have been used in stone fronting a house, near to the Post Office on Manor Road. The site has been somewhat blighted by plans for Brimington Staveley bypass, which passes directly over the station site and much of the track of the former MS & LR in the area. Whether this by-pass will ever be built remains to be seen. Part 8 – MAINLINE ( & LOOP) IN THE SHADOWS… There have been a number of theories expounded as to why the MS and LR’s/GCR routes, in particular their main line to London, faired so badly from the 1950s. In this part we examine these theories. THE SEEDS ARE SOWN We have already explored the less than pristine condition of stations on the line in LNER days, along with the fact that the East Coast route was always a more glamorous prospect for what investment that company was able to make. The LNER had failed to generate enough profits for a dividend to shareholders from 1935 to 1945, whilst the period 1929-34 saw an average of only 0.54%. Clearly money was tight in LNER days. GCR interests were, however, represented on the new LNER Board, notably by Lord Farringdon (the former GCR Chairman), who was vice-chairman. The LNER’s immediate postwar development plan, whilst covering the ex Great Central main line did not feature any major new works on the loop . The nearest proposed improvements were at Annesley for siding alterations and at Sheffield. There were some other non main-line improvements scheduled at Langwith and Mansfield, along with national initiatives including track renewal on the ‘6,000 miles of the LNER system’ . There was one big project on the GCR of perhaps national significance – electrification of the Manchester to Sheffield and Wath line. This had been started before the war. As previously discussed, the ‘Big Four’ railway companies on nationalisation in 1948 came under control of the Railway Executive of the British Transport Commission (BTC). LNER lines in the south of the country were grouped into one of six regions, known as the Eastern Region. The Railway Executive was abolished in 1953, with an enlarged BTC assuming control of the railways. There were then six area boards with accompanying divisions – still based on the regional structure. Regional management and the problems of regional boundaries seems to have been under review during the lifetime of the Railway Executive and the BTC, particularly regarding number, shape and size. There was also some debate about the issue of ‘penetrating lines’. These were through lines, wholly administered by one region, even where they passed through one or more other regions. It is important to dwell on this issue, as the former Great Central was in this category. The potential of transferring the line north of Aylesbury from the Eastern to the London Midland had been raised by the Railway Executive early in its life, but had not found favour at that time with the ‘…Chief Regional Officers concerned’. In 1956, the ER had introduced a successful ‘line’ management concept , which ultimately saw the GC grouped with what was termed the Great Northern lines (London-York-Newcastle – the ‘East Coast’ route from London Kings Cross). The issue of penetrating lines remained, however. There were various solutions proposed but this was finally resolved from a GC perspective, if this is the correct word, on the 1 February 1958. On this date the old GC main line passed from Eastern Region control to London Midland Region (LMR) southwards from Pilsley, with conversely the former Midland line passing from London Midland to Eastern Region control at Horn’s Bridge. It is as this stage that the majority of the former GC main line to London came under LMR control. This meant that through trains from London and those on the loop from Sheffield to Nottingham or Leicester required inter-regional co-operation. On the GC north from Pilsley the Eastern Region held sway. Michael Bonavia in his book The Organisation of British Railways, gives some revealing details on how the former GC line was seen at the time of its near wholesale transfer to the London Midland Region; IN THE SHASOWS The run down of the Great Central passenger traffic had, however, commenced earlier than these late 1950s changes. At the end of this decade railway author Cecil J Allen concluded that the GC’s express passenger trains never recovered from reductions caused by the Second World War. Never-the-less the GC line did still have some prestige express services. The Sheffield Victoria to London Marylebone and return ‘Master Cutler’ was the name given to what pre-war had been known as the breakfast car express service. Reintroduced after the war, it was named from the 1947 winter timetable. A second named prestige express, ‘The South Yorkshireman’, was a British Railways’ innovation. Introduced in May 1948, it ran from Bradford to Marylebone and return. Early in life, this train had stopped at Chesterfield, but this was cut due to poor patronage. The service disappeared altogether in 1960. The ‘Master Cutler’ has a more varied history. It was diverted via the Great Northern line into Kings Cross station, becoming a diesel hauled all Pullman express, from September 1955. In 1971 the train moved to Sheffield Midland with Pullman status withdrawn. ‘The Master Cutler’ is still with us today, calling at Chesterfield, which it never did in its GC route days. The 1950s were a turning point in railway finances. From 1954 the national operating account plunged into the red and freight declined, followed later by passengers carried. In 1954 The Central Transport Users Consultative Committee reported that it had dealt with 102 proposals for the withdrawal of branch line facilities, with recommendations made for closing 68 lightly-used stations. TUCCs, as they were called, were a statutory body designed to consider and make recommendations on service and facility proposals to the Minister of Transport. 1955 saw publication of the British Transport Commission’s report Modernisation and Re-equipment of British Railways. This set-out a strategy for modernisation across all spheres of railway activity. The GC was classed as a secondary main line and was to be fully dieselised, though in reality this did not happen. Clearly, though, the pace of change and the urgency for it was quickening. Ken Grainger in his Sheffield Victoria to Chesterfield Central Derbyshire Lines book reproduces what he describes as a rather ‘plaintive’ mid 1950s handbill, advertising express services. Three of these ran along the loop, calling at Chesterfield. The handbill ‘Marylebone for the Midlands and Manchester’ points out that ‘there is more room [on these services]…and they all have restaurant cars’. A further example of the run-down prior the Eastern Region split is found in a letter carried in the December 1957 edition of Trains Illustrated. Headed ‘Decline of the Great Central’, the writer, from Sheffield, claimed that there had been no improvement in GC section services since 1948, with track standards poor. He evidenced the run-down further by stating that ‘every single daytime train from Marylebone to Sheffield is duplicated by a much better train from St. Pancras.’ Even at this time it appears that there was some speculation on the line’s future with ‘…disturbing rumours that reach Sheffield from time to time about the complete closure of the Marylebone line to express passenger services…’ These rumours were well founded. A little over a year later, in early 1959, Eastern Region, Great Northern line traffic manager GF Fiennes commented that ‘duplicate’ lines should be closed, naming the Great Central as one. By this time, as we have seen, the majority of the GC route was in London Midland Region hands. By the summer of 1959 services on the line were proposed for serious curtailment by the LMR. In an appraisal of the Modernisation Plan of that year, published as a White Paper, the British Transport Commission openly stated that most of the GC’s services were duplicated and had lost their former importance. There had been a planned reduction in freight traffic, though Marylebone had been developed as a parcels terminal. The BTC proposed a service between Marylebone and Nottingham. What, in effect, was a staged closure was designed to deliver a saving estimated at £370,000 a year. Stage 1 saw the withdrawal of express trains between Marylebone, Sheffield Victoria, Manchester and Bradford (the ‘South Yorkshireman’ served the later), with last services on Saturday, 2 January 1960. There still remained a night train from Sheffield to Marylebone, with a second in the opposite direction. This left only semi-fast passenger trains from Marylebone to Nottingham Victoria on the GC line southwards, with a York-Bournemouth service (cut back to Banbury in the winter). These curtailments were estimated to save £140,000 a year, The LMR were still, however, painting an optimistic picture, with the Region’s Director of Traffic Services denying, in February 1960’s Railway Magazine, that there were plans to integrate the GC and Midland lines. He is reported as saying that the GC still had a future as a through route for sleeper car services, the ‘Starlight Special’ trains (cheap late night services from London to Scotland) and large coal movements. Never-the-less the same edition reported that the next stage in the GC line economies would be closing some ‘wayside stations between Aylesbury and Nottingham’. Despite the January 1960 service reductions, for the faithful, it was still possible to reach London from Sheffield Victoria, by using local trains. Most of which traversed the Chesterfield loop, mainly running to Nottingham Victoria. These trains, however, did not appear to connect particularly well with the semi-fasts to London. It was also possible to travel from Sheffield Victoria to Manchester London Road, on the electrically hauled service, which had been fully introduced from 1954. CP Walker writing in The Railway Magazine of March 1960 was not optimistic of the line’s passenger carrying future. He noted that a dieselisation policy on the Midland lines had already adversely affected customer numbers between Nottingham and Leicester and there had been poor publicity for the route. In December 1960’s Trains Illustrated, Brian Perren reviewed the situation on the GC following the stage I withdrawal. He thought that there was a future for the line, in particular its ‘…most valuable part…the middle section from Woodford to Nottingham.’ Whilst the days of the GC as a northern route to London where clearly numbered, Perren thought that it still performed an important role as a north to west route via connections at Banbury, ‘with freight traffic predominating.’ Much of this freight was from the coalfields, particularly from Annesley yards, where trains were run to Woodford at speed and to strict timings. Perren also lists other long distance freight routed via the GC. Passenger workings included a daily Newcastle – Bournemouth passenger, York – Swansea, with various through holiday services from Sheffield to the south. The ‘Starlight specials’ were listed along with three ‘car-sleeper’ trains. Perren thought there was a future for the GC but not the remaining London-Nottingham semi-fasts. Most, if not all, of this traffic would not have travelled the loop, unless diversions were necessary. The LMR had developed a freight traffic plan the year before Perren’s article, with some promise of developing the route, but little had happened, save introduction of two night trains. The former GC route was still creditable performer some three years later, with 100,000 tons per week of consigned freight recorded in our area, but this tailed off dramatically towards London. One of the photographs accompanying Perren’s article shows a train leaving Chesterfield Central, captioned ‘There are reports that British Railways seek to withdraw passenger services from the Chesterfield Loop’. With the spotlight on a main-line run-down, it is perhaps not surprising that the loop was but a bit-player in the saga of the ex GCR lines. As discussed previously, traffic was never very high on the loop. Grassmoor station had closed on 28 October 1948 , with the next station to close being our own Sheepbridge and Brimington at the end of 1955. A year earlier Beighton Station, on the main line from Staveley to Sheffield, had closed. An analysis of passenger traffic carried out by BR for the week ending 19 August 1961 , painted a fairly bleak picture. Chesterfield Central saw a total of 1,829 passengers either alighting or joining that week, whilst the nearby Midland Station, with its considerably better service of local, cross-country and London trains, saw 22,285. Staveley Central saw 1,072 passengers, whilst Staveley Works saw a lowly 288. Chesterfield Central, and Staveley Works were the only two stations then open on the loop. By comparison, Sheepbridge, enjoying local passenger services on the Midland, saw a fairly respectable 709. CLOSURE PROPOSED This route-wide opposition had some effect, as the East Midlands Transport Users Consultative Committee was reported, in the first half of 1962, as not being entirely satisfied with the proposals. The TUCC wanted to see a local passenger service from Rugby, Leicester and Nottingham. Unfortunately the East Midlands TUCC did agree to ‘…a Sunday shut-down of the line for passenger services throughout the affected length; to the withdrawal of the local week-day passenger services also between Nottingham and Sheffield Victoria; to the closure of the Chesterfield Loop…’ with the closure of several stations. In June 1962 Modern Railways magazine carried a brief photographic feature ‘Main Line in the Shadows’ complete with pictures on the Chesterfield Loop. The East Midland’s TUCC thoughts on closures were supported by the Central TUCC, with the Minister of Transport ultimately agreeing to closure of the Chesterfield Loop and all local services between Nottingham and Sheffield. The Minister had previously agreed to the Sunday service cuts from 10 March. The services between Rugby and Nottingham were to run, but in our area services were to cease. Special arrangements were made for extra bus services from Tibshelf, for workers travelling to Nottingham. The axe fell swiftly, with the end for passenger services on the loop and local services in the area on Sunday 3 March. The last up train to depart from Chesterfield Central on that final Sunday would have been a ‘through train Manchester to Nottingham’; departing 4.40 from Manchester Piccadilly, calling at Chesterfield 6.52, arriving Nottingham at 7.43pm and then onwards to Leicester for a 8.23 arrival. The last down train was timetabled to arrive at Chesterfield 10.27 pm – having been a local that departed Nottingham Victoria 9.35 pm - arriving Sheffield Victoria at 11.9 pm. Locally, Eastern Region stations closed were Killamarsh Central, Renishaw Central, Staveley Central, Staveley Works, Chesterfield Central and Heath, with Tibshelf (in London Midland territory) also closed. Facilities for parcels traffic remained at Heath, Staveley Central, Renishaw Central, with freight services not being affected. If required Heath, Staveley, Renishaw, and Killamarsh were to be opened specially for holiday and excursion trains. Despite this closure the main line route was apparently still used extensively for the through weekend summer holiday trains between Sheffield and Banbury. DR. BEECHING AND HIS REPORT What the report did do was name the York-Sheffield Victoria-Nottingham Victoria-Leicester Central-Banbury and London Marylebone-Leicester Central-Nottingham Victoria passenger services for closure. This would effectively be the end of the GC main line as a passenger route. To underline the point about unrenumerative services, short clips of the GC line were included in a documentary made by British Transport Films on the Beeching Report. There were also reported leaks from the British Railways Board that the GC main-line was to be closed for freight. But as we have seen, the GC closure was perhaps the culmination of plans hatched some years earlier, originally before Beeching’s time. Beeching no doubt took the ‘bull by the horns’ so to speak. It was clear that in his new railway, as Modern Railways put it, ‘…the GC line is redundant—even as a relief route for, say, coal in a severe winter.’ The Beeching report started a series of local and route based campaigns to save various lines and stations from closure, across the country. The GC had its own campaign, spear-headed by the Great Central Railway Association, who wanted to see the line either retained, worked for them by the BRB, or turned into a giant preservation scheme. This campaign largely failed, although many members of the GCRA later went to form a group that was responsible for successfully preserving part of the main line from Loughborough to Leicester – the Main Line Preservation Group (later the Main Line Steam Trust). THE END The plan was carried into effect on 1 March 1965, when all through goods traffic was diverted, followed by mineral traffic on the 12/13 June of that year. This effectively saw the end of Staveley shed, which closed on the 3 October 1965. As late as 1962 the depot (41H in BR’s shed coding system) was reported have been undergoing repairs . In December 1964 there were still 52 drivers, 16 passed firemen, 30 firemen, 10 passed cleaners and 22 maintenance staff at the depot. On 20 February 1964 it is recorded 21 steam locomotives were allocated, for some 22 booked workings. On 3 September 1966 the GC’s brief existence as a main line route finally came to an end. The residual passenger service then comprised: