1940s Miscellany

© Cambridgeshire Collection

The above image of Cambridge station booking hall has appeared in a couple of publications and is often dated to c1950. However, it has been the subject of some examination by both your author and the staff of the Cambridgeshire Collection with the conclusion being that it was taken during wartime. The young man towards the right appears to be wearing a military uniform, possibly American. The two posters behind him are both headed London & North Eastern Railway and London Midland & Scottish Railway with the information given appearing to concern alterations and / or reductions to train times due to the war. To the left of the central pillar is an LNER poster, again appearing to concern train times. Below the Enquiry Office sign and partly obscured is a notice headed British Railways and under magnification appears to direct enquires to an address on Station Road; possibly due to wartime staffing reductions. British Railways will be the collective name for the Big Four as explained earlier.

The LNER poster is pasted onto what was a departures indicator. This was similar in operation to a destination blind on a bus and was wound-on, believed manually, at intervals as trains departed. Obviously out of use and replaced by the poster when the photograph was taken, this also suggests wartime. After the war, the departures indicator was reinstated and it remained in use until 1971.

The booking hall originally consisted of two separate ticket offices and one exit from the platform. One or two ticket windows issued only London tickets and the rest issued tickets on an alphabetical system; Stations A to K and Stations M to Y. Signs above the ticket windows indicated what was sold where although there is no evidence of this system above. The booking was, and still is, behind the central three colonnade arches but with only one arch being used for access.

Note the rather muddled gating system; the partially obscured sign in the centre says Train Departures but the gate on the left is the way onto the platform. The other gates were closed much of the time and tended to be used only during the evening peak. Even at the time of writing, access to the platform is not exactly conducive to the free flow of the commuting masses. There were two other exits from the station; one from platform 6 and another from platform 3 but they were more of an emergency exit nature and seldom used for normal passenger flows although that on platform 3 would occasionally be flung open during the evening peak but there were no ticket checks.

The Eagle Star office on Peas Hill (a street in the centre of Cambridge near the market) is now, at the time of writing, an oriental food outlet.

Photo by John Ford from David Ford's Flickr photostream

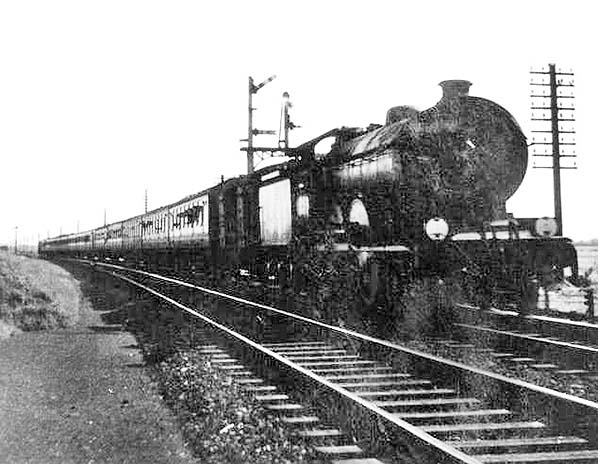

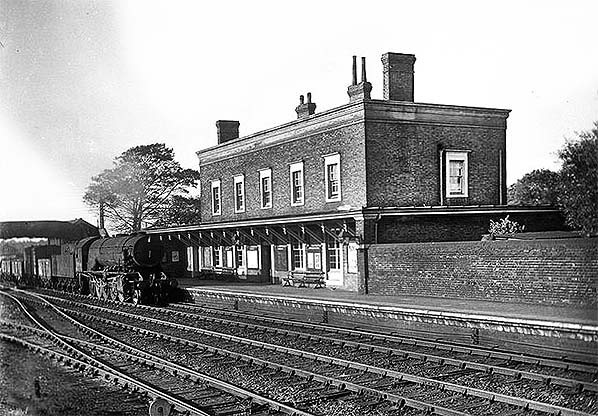

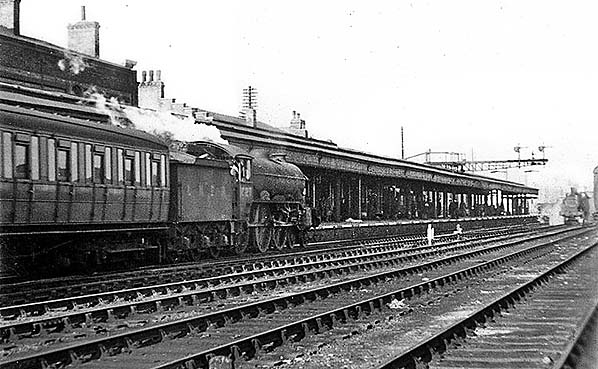

Above; an unidentified B12 approaches Cambridge with a troop train probably in 1947. Such trains, lengthy and with many heads out of the windows, were a common sight in the years immediately following the war as troops returned home. It was often the case that families and loved ones were unaware of the troops impending arrival; the men simply arriving at their front doors unannounced. During the war, wives and girlfriends sometimes became involved in wartime romances which in some cases developed into full-blown relationships. Therefore the return of troops could change on the doorstep from a feeling of joy to one of utter despair. This was, it could be argued, an effect of war and one which is rapidly becoming forgotten with the passage of time.

The train seen above is approaching Cambridge from the London direction and is about to pass beneath Long Road bridge.

Photo by John Ford from David Ford's Flickr photostream

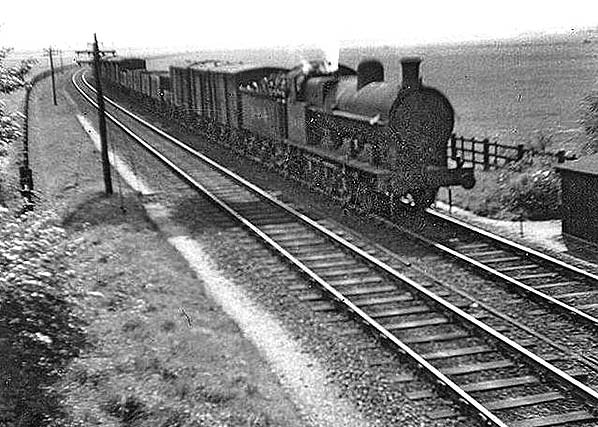

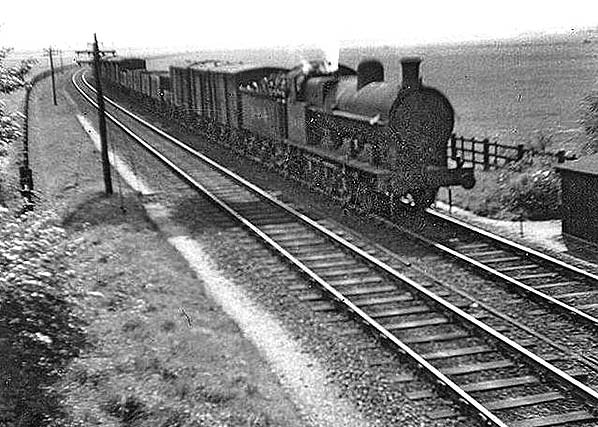

Very likely taken at the same time as the previous image, above is an LMS G2A 0-8-0 Super D, possibly 9178, approaching Long Road on the Bedford line. The G2As were an LNWR design and essentially a higher boiler pressure version of the G1. Despite the apparently rural setting, the train is actually in Cambridge and only about ¾ mile south of the station. The guided busway now occupies the scene above. See below for a comparison.

Photo by Sebastian Ballard reproduced from Geograph under creative commons licence

Taken in August 2009, the concrete tracks of the guided busway now lie where the G2A once trundled. Years late and massively over-budget, it would be a further two years before the busway would open at the time the photograph was taken. The original cost estimate was around £60 million, the final cost was triple that estimate.

In a sense, the guided buses hark back to the rubber-tyred Michelin railcar which could, some 75 years earlier, be seen passing this very same location.

Photo by John Ford from David Ford's Flickr photostream

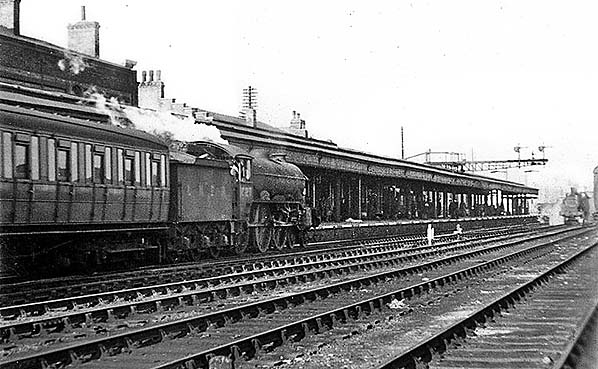

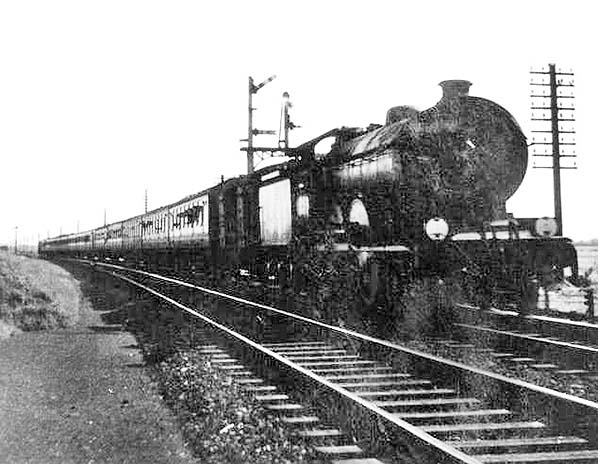

Above Stanier Class 5 2-6-0 No.2949 can be seen with an unidentified 4F 0-6-0 at Cambridge station in 1947. The pair would have arrived off the Bedford line and are probably heading to the engine shed for servicing. Double heading was not uncommon on the LMS route to Cambridge; the 4F would probably work back alone to Bedford or Bletchley on a goods train. The Oxford - Bletchley - Cambridge line was something of an LMS outpost insofar as the Bedford - Cambridge section was concerned, yet throughout its existence it saw a surprisingly wide variety of motive power and was to become the final route by which steam locomotives in normal service appeared at Cambridge with Black 5s, 8F's and BR Standards putting in the occasional appearance up to 1965. Cambridge shed had closed to steam in 1962 but basic facilities existed for a few more years.

The 4F 0-6-0s appeared at Cambridge on both passenger and goods trains. On the preservation scene one Stanier Mogul, BR 42968, has survived out of a total of 40, while three LMS-built 4Fs have survived out of a total of 575 and just one Midland-built example out of a total of 197.

Photo by John Ford from David Ford's Flickr photostream

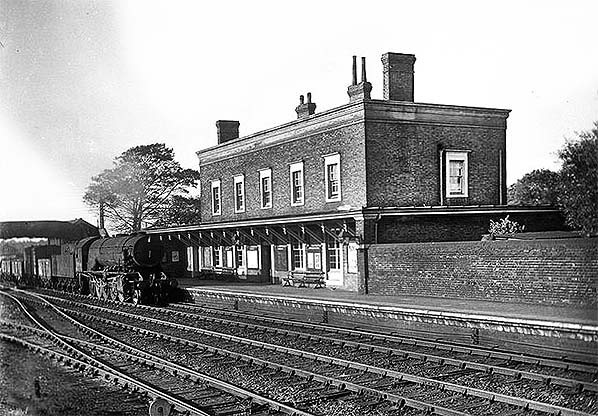

Still in 1947 and sitting at the same spot as the 4F in the previous image is LNER B17 No.1267 'Aske Hall' having arrived with a train of suburban stock. Very common at Cambridge, the B17s, also known as the 'Sandringham' or 'Footballer' class, were a means to an end. Gresley was faced with two problems; the B12s were struggling with increasingly heavy trains and they were weight restrictions on the former GER main lines. The answer was the B17, the first of which appeared in 1928 and 73 were built.

In 1937 two were rebuilt with A4 style streamlined casing for use on the East Anglian named train. The two involved were 2859 'Norwich City' and 2870 'Tottenham Hotspur' and were renamed 'East Anglian' and 'City of London' respectively. The 'Norwich City' name was previously on 2839 'Rendlesham Hall'. To make things a little more confusing, 2870 was originally named 'Manchester City' but that name was transferred to 2871 when the latter was new in June 1937 but it appears No.2870 never appeared in service with that name and appeared ex-works as 'Tottenham Hotspur' but the latter name had graced 2830, which was originally 'Thorseby Park'. Got that so far? Good because there's more. In April 1946 'Manchester City', that is, the 2871 incarnation, was renamed 'Royal Sovereign 'and this locomotive was rebuilt into a Class B2 in August 1948 by Edward Thompson. Withdrawn in September 1958, the 'Royal Sovereign' name was then transferred to 2832 'Belvoir Castle', this locomotive then being withdrawn in February 1959 having also been rebuilt as a B2. In case readers have not already guessed, 2839 was to become another of the B2s.

'Royal Sovereign' was one of two Royal Train locomotives, the other being 2817 'Ford Castle' - another rebuild to Class B2. The two A4 lookalikes were altered back into conventional form 1950. 'Aske Hall' led a less hectic life; she was altered to a member of the B17/6 sub-class in 1948 and was withdrawn in July 1959. No B17s or B2s survived the scrapyard but a few nameplates survive, having been presented to their football club namesakes by BR.

One other detail in the above image is of note; the black and white platform edging. This had been introduced during the war as a safety measure during the blackout and it remained on the platform at Cambridge for several years. As Mr Hodges would have said, it was an ARP matter. After the war some stations maintained this style of edging and a notable example was Burwell, on the Mildenhall branch, where the black and white had all-but worn away - only to be repainted shortly before the station closed.

Photo by John Ford from David Ford's Flickr photostream

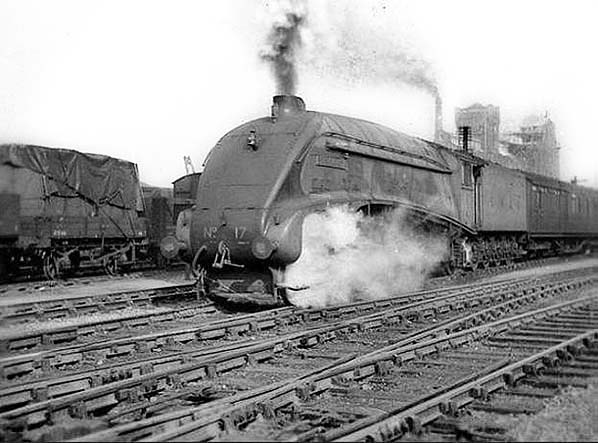

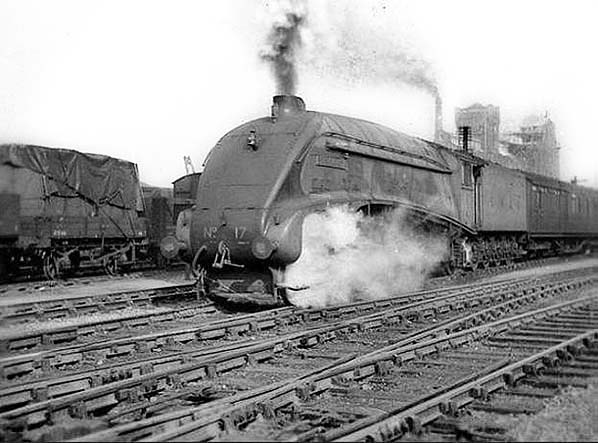

Still in 1947 but this time at Cambridge South we see A4 No.17 'Silver Fox' departing on a stopping service to King's Cross. The Gresley Pacifics were a not infrequent sight on King's Cross semi-fast and stopping services and looked rather odd hauling rakes of suburban stock. The short run to Cambridge was used by King's Cross shed for running-in turns and fill-in turns, usually the latter, and this practice continued into diesel days. There was a similar service on the Liverpool Street line in the evening peak used for the running-in of locomotives ex-Stratford Works.

'Silver Fox' is almost certainly in garter blue livery. She carried a stainless steel fox on each side of her casing (just visible above) and was from the first batch of four A4s built to operate the Silver Jubilee train. The names of all four contained the word 'silver;, the others being 'Silver Link', 'Quicksilver' and 'Silver King'. Originally numbered 2512, 'Silver Fox; became No.17 under the LNER renumbering scheme of 1946 and then 60017 under BR. She was withdrawn in October 1963 and, like the other three Silver locomotives, did not survive into preservation.

Photo by Ben Brooksbank

Just for comparison, above is 'Silver Fox' in June 1946. The location is Finsbury Park and the train is an up stopping service from Cambridge again formed of suburban stock. Still numbered 2512, 'Silver Fox' appears to still be in wartime black livery but has the full LNER initials on the tender rather than the wartime NE. The stainless steel fox is much clearer in this image.

Today is it easy to forget that streamlined locomotives were once a familiar sight at Cambridge. The A4s appeared on both local and diverted trains, the two streamlined B17s also appeared as did Class W1 No.60700, the converted former experimental 'Galloping Sausage' which had also received A4-style casing. Furthermore and as will see later, 'air smoothed' Bulleid Pacifics from the Southern Region also came to have a look at Cambridge after nationalisation.

Photo by John Ford from David Ford's Flickr photostream

An unidentified WD 2-8-0 takes on water on the up goods loop at Cambridge, opposite the former GER goods shed. We have already mentioned these locomotives, classified O7 by the LNER, which were an austerity version of the Stanier 8F; the most obvious difference being the parallel boiler but a number of other economy measures were incorporated. Like the similar 2-10-0 version, they were designed for cheapness and quickness of construction but not for long lives. Nevertheless, many survived with BR into the 1960s with the final examples not been withdrawn until 1967. Of the 935 built, many served abroad and some ended up as far away as China. BR ended up with no less than 733 examples, 90000 - 90732. The sole preserved example in Britain was a re-import from Sweden and had been hidden away as part of that country's strategic reserve. It carries BR livery and the semi-ficticious number 90733. There is an amusing story to the number 90733. In 1954 a much-travelled Stanier 8F had ended up on the Longmoor Military Railway but was involved in a collision with a diesel shunter. The army sidelined the 8F, then transferred it to BR in 1957 who repaired and overhauled it. Someone within BR managed to mistake the 8F for a WD 2-8-0 and numbered it 90733. The mistake was realised and the 8F then took the next available number in the 8F series, 48773 but it is not known if the locomotive actually escaped from Crewe works bearing the wrong number

Photo by John Ford from David Ford's Flickr photostream

The WD's specification included the ability to handle trains of 1000 tons at 40mph and presumably this was on level track. Other criteria were the ability to burn poor quality fuel (although quite how this was expected to be achieved given the type of firebox fitted is unclear); the ability to continue running under conditions of poor maintenance; the ability to continue running with a degree of abuse and handling by unfamiliar crews. Their low speed capability was deliberately designed, in order to keep heavy trains moving regardless of prevailing conditions. The WDs had their problems but overall they were rather more successful than the USATC S160s. On the down side, the WDs were rough riding and their motion, that is, their coupling and connecting rods, had a habit of clanking loudly.

The image above shows WD No.77450 heading north beneath Hills Road bridge with a Class 8 goods train. The train is taking the through goods roads as seen in the previous image. A large number of these WD-hauled trains passing Cambridge operated between Temple Mills and Whitemoor, either via St Ives or Ely, and dozens of such trains would pass Cambridge in one direction or the other each day.

The WDs nominally had four-figure War Department numbers and those intended to be sent abroad had 70000 added to their numbers. In the event not all of them went abroad.

When the photograph of 77450 was taken, the fun was yet to start. 77450 was built at Vulcan Foundry in 1943, works number 5006 and was to become one of twelve of the type sent to China for use on the Kowloon - Canton Railway (KCR). She arrived at Hong Kong in February 1947 and become KCR No.30 and was withdrawn in August 1957. The Kowloon - Canton Railway is still in operation but as part of MTR; the Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway Corporation.

At the end of the war, the twelve WDs which ended up in China were put into storage at Longmoor before being overhauled at Woolwich Arsenal and shipped from Tilbury. The above image of 77450 could, therefore, possibly be one of the very few photographs taken of trains at Cambridge during wartime but in the absence of the date the locomotive was sent to Longmoor we cannot be certain.

Those which, postwar, passed into LNER ownership were given numbers in that company's series although it is possible not all carried them. British Railways initially renumbered then in the 6xxxx series and then the 9xxxx series as mentioned earlier.

As with WD7337 'Sir Guy Williams', the Soham locomotive, Bachmann have also produced a model of KCR No.21 which began life as WD No.78660.

Photo by RuthAS reproduced from Wikimedia Commons under creative commons licence

As previously mentioned, the WD 2-10-0 also appeared at Cambridge but we have had to use a photograph taken elsewhere in order to adequately illustrate the type. Above is Army No.601 'Kitchener' at Carlisle Kingmoor, possibly during 1968. The tender is lettered LMR (Longmoor Military Railway) and the locomotive was withdrawn and believed to be en-route to the scrapyard, with nameplate and motion still in position, when photographed. Not visible but also present was 'Sir Guy Williams', also heading for the scrapyard. 'Kitchener' appeared briefly in the film 'The Great St Trinians Train Robbery', which was filmed at Longmoor, and was dressed-up in a rather makeshift rendition of BR green livery. Sister (brother?) No.600 'Gordon' has of course survived into preservation. After the war, 25 of the type ended up with BR; these were WD 73774-73798 and became BR 90750-74. They operated mainly in Scotland and all had been withdrawn by 1962. The preserved 90775 is a re-import from Greece together with 73672, while a fourth example, once No.73755, survives in the Nederlandse Spoorwegen museum, Utrecht. This had become NS 5085.

Photo from Duncan Chandler's GER Album

We can, however, offer the above but it is by no means clear. A WD 2-10-0 passes Great Chesterford with an up goods train. Unfortunately both date and locomotive identity are unknown. This platforms at this station were staggered; the down platform being the other side of the footbridge, but alterations to accommodate longer trains has meant the down platform now extends further south and covers the site of the nearest track. Signalling at Great Chesterford was interesting (click link),

The other wartime type which appeared at Cambridge, excepting the Austerity saddle-tanks, was the USATC (United States Army Transportation Corps) S160 2-8-0. No photographs of this type at Cambridge have come to light so we will use one of a preserved example.

Photo by Geoff Sheppard reproduced from Wikimedia Commons under creative commons licence

Above is 6046 on the Norton Fitzwarren triangle, West Somerset Railway, in March 2013. Some 800 of these locomotives were built in the USA by Alco, Baldwin and Lima during 1942-3 and shipped to Britain. Many were stored in South Wales awaiting D-Day but 160 were put into service by the LNER with 21 allocated to Stratford and no less than 50 to March. As a result they were a common sight at Cambridge and in other parts of southern East Anglia.

The S160s were based on a WWI Baldwin design and incorporated some features of the S200 2-8-2; another American design for the British army but none of which saw service in Britain. Built along the same austerity lines as the Riddles 2-8-0s, the S160s were powerful locomotives and free-steaming but they had their problems. The major problem was the firebox roof stays which were prone to failure, resulting in collapse of the crowns; one, on the Great Western Railway, exploded, killing the fireman. Another exploded at Thurston (on the Cambridge - Ipswich line) injuring the driver and blowing the fireman off the footplate. Other problems were poor braking and difficulty negotiating curves.

Built to British loading gauge the S160s, as the image above shows, were very American in appearance. Note the Westinghouse pump mounted on the smokebox. Lettering on the tenders ensured nobody could miss the origin of the locomotives but the lettering varied across the class.

At the end of the war in Europe, none of the class remained in Britain and as might be expected many ended up in far-flung corners of the world. A number have returned to Britain for preservation, especially from Hungary and Poland where, in the latter country, the PKP (Polskie Koleje Państwowe) made use of them until 1980. No.6046, (Baldwin 72080), was repatriated from Hungary. Some S160s ended up in China where at least one is believed to have continued in service until as late as 1997. Yet more ended up in Russia (both broad and narrow gauge), Jamaica, North Africa, South America - the list is endless.

Some remained in the USA while others, together with some Stanier 8Fs and other types, are now allocated to sheds at the bottom of the sea as a result of enemy action.

Photo by John Ford from David Ford's Flickr photostream

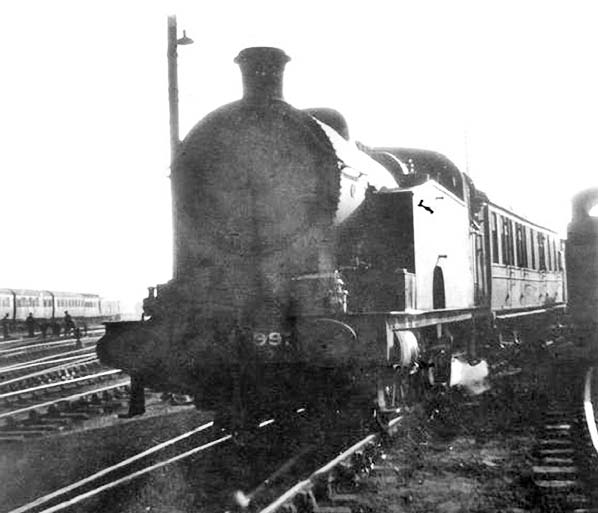

Sadly the above image is of very poor quality but is included as it shows a Cambridge rarity; Class Q1 0-8-0T No.9926 in 1947. It later became BR 69926. These locomotives were another product of war; it had been planned to rebuilt 25 ex-GCR Class Q4 0-8-0 tender locomotives into 0-8-0Ts to fulfil a requirement for heavy shunting locomotives but in the event only 13 were converted. The reason for 9926 being at Cambridge was most likely the hump yard but it seems to have spent much of its time sitting chatting to the Cambridge breakdown train, which is what it is doing in the above image. As BR 69926 it later moved to Frodingham, Scunthorpe, a location which was associated with many of the class.

Photographic evidence shows that at least one of the class, which, as it happens, was 9926, carried the LNER 'eye' logo in the form of cast plates on the sides of its bunker rather than the more usual oval works / numberplates. All of these Thompson 1942 - 1945 rebuilds had been withdrawn by, or during, 1958. Several were scrapped at their place of birth, Gorton works.

The Winter of 1946/7

Britain and much of Europe once again found itself in battle, but this time the enemy was the weather. Freak conditions which began in December 1946 saw snow drifts several metres deep, rivers frozen (including the Cam), coal stockpiles frozen solid, food and livestock perishing, ice floes off the coast of East Anglia, roads and railways impassable with vehicles of both modes trapped. Temperatures remained below freezing for weeks with the coldest location being Woburn, Bedfordshire, which at one point was as cold as -21°C. Industry virtually ground to a halt, rationing - still in force from WWII - was reduced further and planned power cuts were introduced.

In Cambridge, soldiers, British and Polish, as well as prisoners of war, were put to work clearing the railways of snow drifts. Following the end of WWII it took some time to repatriate allied soldiers, such as Poles, and POWs but some of the latter chose to remain in Britain following release. To this end POW Camp 45 at Trumpington remained in operation until July 1947, by which time it housed Polish soldiers and displaced persons; the POWs by then being mainly billeted on farms where they worked. It was Camp 45 which supplied much of the labour used in clearing the railways of snowdrifts, which had been compounded by howling winds, in the Cambridge area. Camp 45 was located on the west side of Hauxton Road, just south of the Bedford line and the present-day Park & Ride.

In the middle of the big freeze there had been a brief period of thaw before the wrath of the weather presented itself once again. Finally, in the middle of March, the weather improved but this brought further problems - floods. Strong winds continued and the thaw left the Fens looking more like the sea than an inland region. The River Cam caused floods but Cambridge, being south of the Fens, escaped the worst effects of the floods. Nevertheless, railways to the immediate north of Cambridge became flooded, with the best known perhaps being the area around Swavesey on the Cambridge - St Ives - March line. The Ely line was also affected, as was parts of the Mildenhall branch. Once the snow and ice had gone, however, the railways were able to provide a reasonable service, with efforts concentrating upon the moving of fuel and other essential supplies. It was during the big freeze, incidentally, that the LNER experimented with an aircraft jet engine mounted on a flat wagon to clear snow from the tracks. Pushed by a steam locomotive, it worked but caused problems with flying ballast and damage to wooden structures.

It is said that the handling of the 1947 winter was the catalyst which brought down Clement Attlee's Labour government, replaced in 1951 by the Conservatives with Winston Churchill as Prime Minister. The details are complex and beyond our remit, but suffice to say the word scapegoats comes vividly to mind.

The Transport Act 1947

As we have already seen, bringing the railways under government control during WWI was considered to have offered a number of benefits which ultimately resulted in the 1923 Grouping. Following WWII the railways were worn out following years of heavy use and minimal maintenance; a situation which also applied to other transport undertakings. Railway companies were in no position financially to rebuild their systems and the political school of thought at that time dictated that money could not be spent unless the industries concerned came under state ownership. In one sense this was the reverse of the present-day situation whereby so-called privatised train companies receive gargantuan subsidies on top of revenue from a fare structure which, in many cases, is quite ludicrous.

Along with the railways, The Transport Act 1947 (the Act) also included canals, sea ports and buses. In the case of the latter, many bus companies were owned by the railway companies and it was this which gave rise to the specific term 'Road Car' in the titles of several bus companies. Once the Act came into effect, buses built up to 1963 by the Bristol / Eastern Coach Works outfit, if not others, bore on their worksplates the Lion & Wheel emblem of the British Transport Commission. Companies of the Tilling Group and BET (British Electric Traction), which had come under state control, were later to form the National Bus Company of which two subsidiaries, The United Counties Omnibus Company and The Eastern Counties Omnibus Company served Cambridge.

One now-almost-forgotten aspect of the Act was the inclusion of the road haulage industry. However, road hauliers objected and with support from many Conservative MPs, then in opposition, road haulage was denationalised once the Conservatives regained power in 1951. The rights or wrongs of this are beyond the scope of this feature suffice to say a) it stunk of the political party ideology which to this day takes precedence over what is best for the nation however well disguised by rhetoric and b) it opened the floodgates for road hauliers to pick and choose what they carried and at prices which suited them, while the railways were obliged to carry anything offered to them and at prices regulated by government. This was to prove disastrous for the railways and for just about everybody else apart from the road hauliers and, ultimately, those hauliers which remained state controlled as part of the National Freight Corporation; the best known constituent of which was British Road Services. This was to become one of the first privatisations under Margaret Thatcher's government, in 1982. The parcels arm of the former BRS became Lynx in 1997.

At midnight on 31 December 1947 the Big Four railway companies ceased to exist and the British Transport Commission came into being on and from 1 January 1948. The railways, London Transport and a few smaller concerns excepted, thenceforth came under the British Railways banner.

Home Page

Home Page