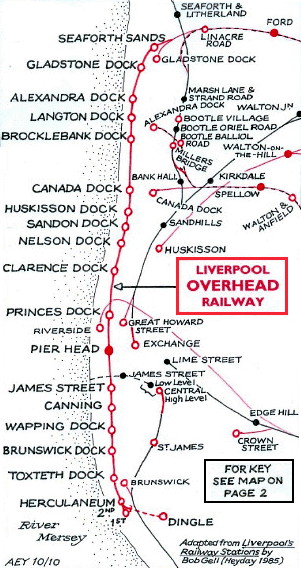

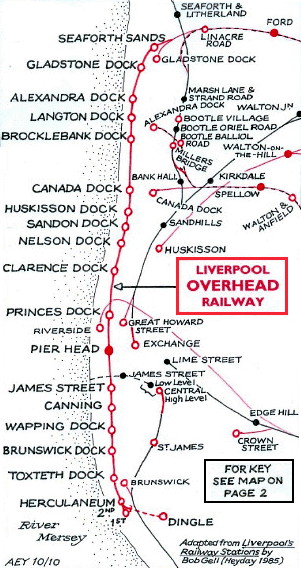

Notes: Dingle station was the southern terminus of the Liverpool Overhead Railway (LOR) which opened in stages between 4 February 1893 and 2 July 1905. In its final form the line was 6½ miles in length running, in the main, adjacent to the Liverpool Dock system on an elevated iron structure that carried the rails 16 ft above street level. From the start LOR train services were electric, using three-coach electric multiple units (EMUs) which drew their power from a live rail located in the centre of the track.

|

The line was an immediate success when it opened in 1893, and it was not long before the first extensions were planned. The 1893 southern terminus was at Herculaneum Dock, close to the residential area of Dingle, but inconveniently located for its residents. To serve Dingle, and thereby increase revenue, the LOR built the ‘Liverpool Overhead Railway Southern Extension’ which consisted of a short section of elevated line and a tunnel ½-mile in length, at the eastern end of which was Dingle station.

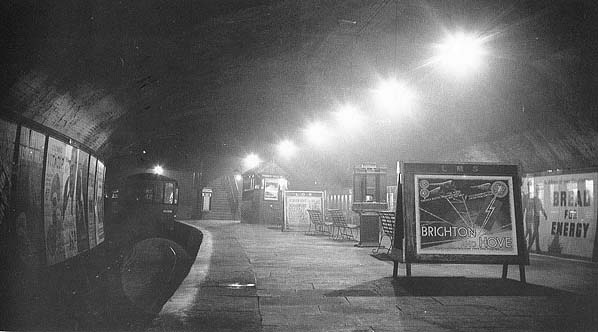

The Southern Extension and Dingle station opened on 21 December 1896. At street level the station was on the western side of Park Road close to its junction with Dingle Lane. The station building was a three-storey brick structure whose canopy extended over the pavement. On the ground floor were the ticket office and a kiosk. On the first and second floors were offices. At the rear of the building a pedestrian subway led down to platform level. Lined in yellow brick the subway was divided into two by a handrail, and passengers descending to the platform were separated from those leaving the station. Within the subway were two sections with steps but, in the main, the subway was in the form of a ramp. |

The subway connected into a large 163yd tunnel which connected to the double-track Dingle Tunnel (through which the line ran to Herculaneum) at its western end, and to a short dead-end tunnel, 123ft in length, at its eastern end. The end-wall of the dead-end tunnel was of bare sandstone. It was left un-faced because the LOR had plans to build an extension further out into the Liverpool suburbs - which never materialized.

From the point where the pedestrian subway entered the large tunnel passengers crossed a single line by an iron footbridge; this connected to a flight of stairs down to an island platform, 28ft wide and 170ft long. The curving platform had two faces and was provided with a ticket collector’s hut and waiting shelters.

At the western end of the platform, just beyond the |

|

ramp, was a non-standard signal box built by the Railway Signal Company with a 23-lever frame. There were two sidings, one on either side of the main line to the west of the box, extending to the double-track portal of the Dingle tunnel. The sidings had buffer stops at the western end set into the large tunnel wall.

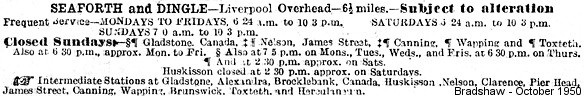

At the time of opening Dingle station had trains every few minutes to Seaforth Sands. Trains entered the station on the north platform face; passengers would disembark, and the train continued into the dead-end tunnel, east of the station. It would then reverse and run into the south platform face to become the next Seaforth Sands service.

|

Dingle had not only the railway line serving the underground station, but also a service operated along Park Road in Dingle by the Liverpool Corporation Tramways Department. Because of this Dingle station also became an interchange facility with many passengers changing between trams and trains. It took only twelve minutes from Dingle to Pier Head station in |

the city centre, close to the ferry terminals. However on 16 November 1898 Liverpool Corporation introduced electric trams to the Dingle route. They were much quicker than the horse-drawn trams they replaced and, although not as fast as the LOR trains, they did run through the shopping district of the city, making them very convenient for the residents of Dingle. The introduction of the electric trams had an adverse effect on the station’s passenger numbers.

On 23 December 1901 an incoming train, the 5:00pm departure from Seaforth Sands, due to arrive at Dingle at 5:32pm caught fire owing to an electrical fault in the rear motor. The fault stopped the train in the tunnel 80 yd from the station. The driver, Robert Ashbee, tried to re-start the train, but this caused arcing which set fire to the wooden body of the rear coach. A strong westerly wind was blowing straight into the tunnel, and the draught fanned the flames. All three coaches of the train were quickly engulfed, and the train was completely ablaze within twelve minutes. There were 29 passengers on board, in addition to the driver and a guard, Charles Maloney. The driver and guard attempted to extinguish the fire in its early stages, but they were unsuccessful. The passengers were evacuated, effecting their escape along the track, then out via the station. Some passengers did not leave the station immediately but chose to linger and watch the fire, which they considered to be too far away from the station to cause them harm.

| At platform level there were three LOR employees, Thomas Rendell (the station foreman), William Owen (a signalman) and J C O’Brien (a car cleaner). Rendell and O’Brien made their way towards the train to assist the driver and guard. Once it was clear that putting out the train fire was hopeless Rendell ran back to the platform and telephoned the booking office asking that |

|

the current be switched off. This was done about ten minutes later, but it simply plunged the station into complete darkness, which did not help matters. By this time lethal, pungent smoke had started to fill the station. Realising what was happening the remaining people in the station attempted to flee. The last three to escape successfully were the signalman, William Owen, a boy called Gough and a Mr Stewart. All three passed out when they reached the booking hall. The driver, guard, foreman and car cleaner were all suffocated to death along with two passengers, Messrs Beadon and Bingham. The bodies of Rendell, Bingham and Beadon were later found at the foot of an air shaft at the east end of the station.

Despite the fact that the train was 80 yd away the fire managed to spread to the station. It did so by first taking hold of a stack of wooden sleepers and then leaping to a train stabled in one of the sidings; it spread from here to the station and completely burned it out. The fire brigade was summoned but there was nothing they could do as the access subway was filled with deadly smoke.

|

The fire had killed six people and resulted in the station being out of use for more than a year. In a Board of Trade Accident Report Lieutenant-Colonel H A York recommended that passenger stations in tunnels should have as little timber in their construction as possible: stone and iron should be used instead. In rebuilding the station the LOR followed this advice. |

On 2 July 1905 the LOR opened a northern extension at Seaforth Sands which provided a connection to the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway (LYR) network. From this date LOR trains had as their northern terminus Seaforth & Litherland station on the LYR Liverpool and Southport line. This provided an even greater range of interchange possibilities for passengers. The service continued to run at a high frequency. The LYR Liverpool & Southport line had been electrified in 1904 but used live rails set to the side of the track. To facilitate through-running the LOR moved its live rails to the same position.

| On 2 February 1906 the LYR introduced a service between Dingle and Southport. To operate it the LYR built special lightweight EMUs designed for operation both on the LOR and LYR systems. By summer 1906 there was an hourly service. In the same year a service was also introduced between Dingle and Aintree Sefton Arms (on the LYR Liverpool and Preston line). The |

|

Aintree service was not a success and was discontinued in September 1908. Twice a year, however, the service ran for Jump Sunday and the Grand National horse races.

The Dingle and Southport service was withdrawn in August 1914 as it was not generating the receipts that the LYR had hoped for. Through tickets between Dingle and Southport were still sold, but passengers were required to change trains at Seaforth & Litherland.

By this time the LOR was carrying millions of passengers every year and many of them were passing through Dingle station. The line was used by dock labourers, sailors, shoppers, businessmen and also tourists. The LOR soon recognised that the commanding views from their trains of the dock estate and the ships within it were an attraction; they therefore provided day tickets allowing passengers to alight and board trains at any of the stations along the line, with unlimited travel. Locally the line became known as the ‘Ovee’ or the ‘Dockers’ Umbrella’. The later name referred to the fact that dockers would walk under its structure in inclement weather to avoid the rain.

|

As a major Atlantic-facing seaport, Liverpool had been crucial to the war effort during the Great War, and the LOR had played its part by moving millions around the dock system. In the Second World War it was called upon to do so again, but in this conflict Liverpool found itself directly in the firing line. Between December 1940 and January 1942 Liverpool was bombed by the |

German Luftwaffe; the worst periods of bombing were in December 1940 and May 1941. The LOR suffered badly and was hit many times, and some of its stations were destroyed. Being underground Dingle escaped unscathed, but during the period there was severe disruption to train services. Because it was an essential transport network for the docks the line was patched up each time it was damaged, and trains were reintroduced as quickly as possible. The last Grand National meet was in 1940, after which the race was suspended owing to the war, and it did not resume until 1947.

After the war the LOR was as busy as ever. There was a boom in trade at the docks, and the railway reaped the benefit. The Grand National was run again on 29 March 1947 - it was moved to a Saturday: before the war it had been run on a Friday - and trains operated between Dingle and Aintree Sefton Arms for the first time since 1940. They continued to do so for every Grand National until the LOR closed.

The railways of Great Britain were nationalised on 1 January 1948, but the LOR remained independent. In the early 1950s the LOR offered tickets to Pier Head from Dingle more cheaply than the corporation tramways; large posters were displayed on the station building advertising the fact. For the Grand National on the 26 March 1955 the LOR ran nine trains from Dingle to Aintree Sefton Arms and charged passengers one shilling single, or two shillings return. The first departure left Dingle at 11:25am and the last at 1:54pm. The journey took 37 minutes. There were seven return workings: the first arrival at Dingle was at 4:28pm and the last at 6:05pm.

| In 1955 an engineering survey was carried out on the iron structure of the LOR. It was discovered that the deck plates on which the tracks were mounted were severely corrode, owing both to the effects of the weather and of smoke from steam engines operated on a dock railway beneath the LOR. The plates needed to be replaced within a few years, and the cost was estimated at £2 million. The LOR did not have the funds |

|

to carry out the work and, although the line was still carrying millions of passengers every year, complete closure of the line was proposed. Suggestions were put forward for saving the line, including taking it into municipal ownership, but none was successful, and the line closed completely on Sunday 30 December 1956. The last departure from Dingle station was at 10:03pm. The last arrival pulled into the station just over half-an-hour later. It was full of passengers who had taken the opportunity to ride on the last train; they were slow to leave the station, preferring to linger in a vain attempt to prolong the life of the line. After they had finally dispersed the station inspector telephoned Seaforth Sands to ensure that the 10:03pm departure had arrived there. As soon as it was confirmed that it had, a switch was thrown. The live rails and signals ceased to have power, and the station lights went out.

At 8:45am the next day (Monday 31 December) the current was switched on and a staff train was run from Dingle to Seaforth Sands; a further service departed in the afternoon. Over the coming weeks trains were transferred from the southern end of the line to Seaforth. On 23 September 1957 demolition began, and the overhead structure was taken down; the process was complete by January 1958.

Dingle station, being on the underground section of the line, survived the demolition, although it had been quickly stripped of its rails. The station was sold to a Rope Manufacturer who used the underground part as a works. In the 1960s the site was taken over by a car repair company. They demolished the street level building and made alterations to the underground section, which included creating a ramp down to track level so that cars could be driven in.

In 1977 the station passed to Roscoe Engineering, who continued to use the site for car repairs and were still using the station in March 2012. Nothing survived of the platform by this time, but the pedestrian subway was little altered, and evidence of the railway in the form of buffer-stops and the foundations of the signal box could still be seen.

On Tuesday 24 July 2012 Dingle made headline news when a section of the tunnel collapsed closing the garage and causing many local residents to be evacuated from their homes.

To read the full Board of Trade report into the Dingle station fire of 1901 click here.

Special thanks to Terry Robinson, Alan Spencer and Nigel Wills-Brown of Roscoe Engineering.

Tickets by Michael Stewart, except 4989 Nick Catford, Bradshaw by Nick Catford and route map drawn by Alan Young.

Sources:

- Disused Stations - Lost Termini of North West England , P T Wright, Silver Link Publishing, 2010.

- Lost Lines - Liverpool and the Mersey , by N Welbourne, Ian Allan, 2008.

- Seventeen Stations to Dingle , John W Gahan, Countryvise Ltd, 1982.

- The Dockers Umbrella , by P Bolger, The Bluecoat Press, 1994.

- The research notes of Tony Graham taken from the National Archives.

|

old10.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Home Page

Home Page