The Military at Marchwood[Source: Darren Kitson] Origin of the Military Presence at Marchwood In 1544 Henry VIII founded the Office of Ordnance, which itself had roots in the aforementioned fourteenth century Privy Wardrobe, and became the body responsible for supplying bows (as in bows and arrows) and early gunpowder weapons to what was then the English military. This does indeed mean English and not British; the British Army in the national sense was not founded until 1661. The Office of Ordnance became at some point in time the Board of Ordnance and which was abolished sometime during the middle of the nineteenth century but the Tower of London continued in its military provision function, by then under the Royal Logistic Corps, until 1994. The Royal Logistic Corps had been formed in April of the previous year by a merger of five former army corps. Gunpowder can be traced back to ninth century China. It is a compound of Sulphur, Charcoal and Potassium Nitrate - the latter perhaps being better known as Saltpetre. It is classed as a 'low explosive' as opposed to 'high explosive', the difference being that a Low Explosive tends to 'flare up', to put it simply, whereas a high explosive detonates. Put another way, a low explosive combusts at subsonic speed whereas a detonation produces a supersonic soundwave which is why detonation of a high explosive produces a loud bang. Under certain conditions, i.e. confinement, gunpowder acts as a reasonably powerful propellant hence its use for centuries in artillery, infantry weapons and pistols where an added advantage was its relatively low power being incapable, usually, of destroying gun barrels. Gunpowder's use as a separate weapons charge, in quarry blasting and so on was phased out towards the end of the nineteenth century in favour of high explosives and, in weaponry, bullets, cartridges and shells in which the charge was, and is, integral. The latter has obvious advantages over the old and slow method of loading gunpowder followed by shot as essentially separate procedures. Nevertheless it is still used today for certain applications and insofar as the general public are concerned it is most familiar as the charge for fireworks where, after firing, the distinctive 'rotten egg' odour caused by the Sulphur content is very familiar. Meanwhile The Royal Navy, Britain's naval force as we know it today, was formed in 1660, there having previously been what might be described as fragmented naval escapades which came and went as occasion demanded. These 'escapades' can be traced back to the ninth century until in the fourteenth century England, again as opposed to Britain, had some semblance of a navy. Historically there had been a number of problems, including alleged corruption, with the arrangements at the Tower of London and perhaps with reservations still lingering but, one can reasonably assume, mainly because of the formation of The Royal Navy it was decided to establish an ordnance depot at Portsmouth. There had been some form of naval presence at Portsmouth for two centuries or more but it was the formation of The Royal Navy which gave birth to what we know today as Her Majesty's Naval Base, Portsmouth.

The new arrangements at Gosport were to prove short-lived, however, and a degree of mystery surrounds events which followed. It seems that partly due to Priddy's Hard being too close to Portsmouth and partly due to a desire to maintain an air of supremacy following the defeat of France at Waterloo (now situated in Belgium) it was decided to create a number of satellite magazines, one of which was to become Royal Naval Armaments Depot, Marchwood. Today the 1494-built Square Tower at Portsmouth still stands and is now used as a wedding venue, for conferences, markets, antiques fares and a host of other purposes. At Gosport the Grand Magazine now serves similar roles and is also home to ‘Explosion! Museum of Naval Firepower’.

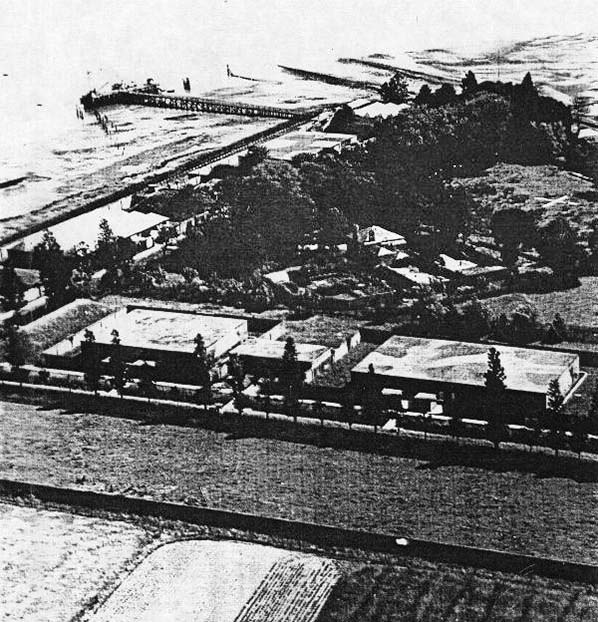

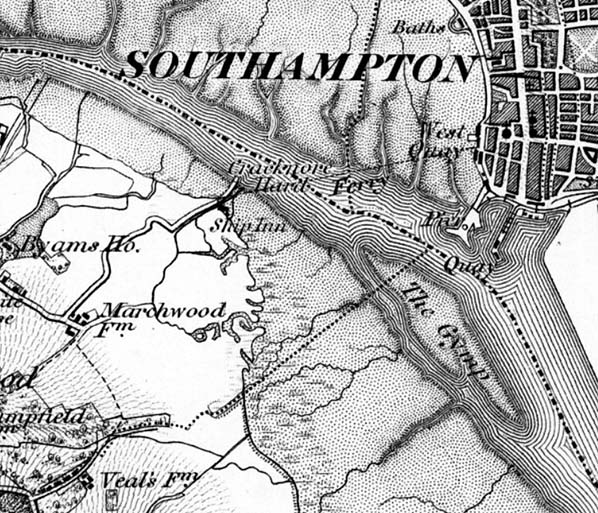

The Royal Naval Armaments Depot (RNAD), Marchwood, came into use in the second decade of the ninetenth century. Sources give a range between 1812 and 1815 but 1812 is the most often quoted year. It was located north of the creek and just north of the present day incinerator and power station and at the shore end of what became Magazine Lane. There were; three magazines, A, B & C; a seawall fronting Southampton Water and continuing part away alongside the creek; Receiving and Examining Rooms; an office, guardroom and barracks facing onto Magazine Lane. In addition there is believed to have been an internal canal system used for shifting barrels around the site, plus barrow-ways and of course a jetty which extended out into Southampton Water's deep water. There was also a commandant's house, located roughly in the centre of the site and with its entrance between the office and guardroom on Magazine Lane. At some stage the house came to be known as 'Ordnance House'. Barrow-ways would ordinarily be used for rolling barrels but there is some evidence trolleys of some description were used at RNAD Marchwood. However, the finer details of how barrels were moved around to and from the barrow-ways, canal system and jetty are rather obscure. The depot apparently closed in 1850, only to reopen again due to the Crimean War which, as with most wars, the British were involved in. The Crimean War kicked-off in October 1853 so presumably RNAD Marchwood had reopened by that date but this time it was to remain open for over a century. The presumed 1853 reopening was to eventually see a number of alterations; circa 1856 four additional and larger magazines were constructed; additional protecting walls were provided at the original Magazines and a western boundary wall was added. Ordnance House may also have appeared at this time as there is some vague evidence the depot was originally (1812) manned by civilians. This supposition has come from a surviving list of names of at least some of the original staff and none had any form or military rank, although this is not conclusive evidence of civilian status. Whatever the truth, there would almost certainly have been some form of military oversee even if not permanently attached.

As the decades passed, the use of gunpowder by the military declined and the magazines gradually shifted to storage of other weaponry including Cordite. First appearing in 1889, Cordite is, like gunpowder, a Low Explosive and became the replacement propellant for gunpowder. Used extensively during the two World Wars, production ceased in the United Kingdom at the end of the 20th Century and its use is now largely phased out. During WWII Southampton and its environs suffered badly from air raids. In 1940 RNAD Marchwood was to cop for it and some of the magazines were destroyed. The damage was quickly repaired and the depot remained in use until 1958 and was finally decommissioned in 1961, there having been a rundown of British military strength during the 1950s and in no small part due to advances in technology. The age of the missile had arrived. Today there is still much to see. Marchwood Yacht Club occupies part of the site and the former office and guardroom on Magazine Lane are now the club's clubroom and committee room. These buildings are original but their colonnades were an 1856 addition. Between these two buildings still stands the gateposts for the now-demolished Ordnance House and complete with house name. The former barrack block is now flats and is named Frobisher Court. Magazines A and C, a receiving room, two examining rooms and all earth-banked blast walls survive. One source describes the blast walls as now being ‘consolidated by mature vegetation and oak and pine trees’ – i.e 'overgrown’.

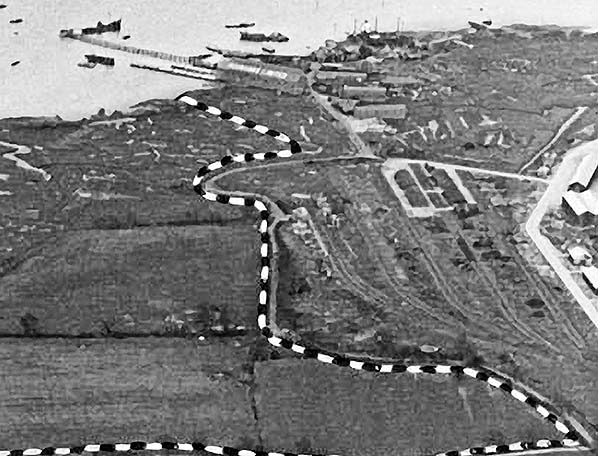

Marchwood Sea Mounting Centre The first visible sign of activity at what would become the military port occurred in 1939 when a railway spur 1¼ miles long was opened to Cracknore Hard jetty and came to be known as the Cracknore Hard branch. For those not familiar with the area, Cracknore Hard is located north of the military port between it and Marchwood Power Station and should not be confused with Cracknore Hard Lane. Little is on record about the spur, other than that it served a magazine and was of course connected to the Fawley branch and thus created what is today known as Marchwood Junction, ie the junction with what became in 1943 the military railway. The magazine (there were actually four within a single compound and are now demolished) was located on the immediate south side of Cracknore Hard and to the north of the creek which marks the geographical northern boundary of the present port area. In March 1993 a railtour, part of which was steam hauled, visited the branch and timings for the tour mention 'Cracknore Hard Jetty' which can only mean the aforementioned location opposite the former Ship Inn which today is occupied by Marchwood Slipways Ltd. The mention of 'jetty' in the railtour timings should not be assumed geographically correct as it is unclear quite when this end of the Cracknore Hard branch, as it was by then known, was abandoned. Either way, there would have once been a level crossing of some description on Cracknore Hard but this should not be confused with the level crossing on Cracknore Hard Lane which existed in the 1950s when a spur was laid in connection with the construction of Marchwood Power Station. This level crossing was located further west. With construction of the military railway proper during WWII the eastern end of the Cracknore Hard branch effectively became a siding while its western end was incorporated into the military railway system to form the present link with Network Rail.

The site which became the military port was in use early in WWII as a base for barrage balloons. These were kite balloons, in other words blimps (non rigid balloons) of a shape resembling an airship but much shorter. Inflated with hydrogen, barrage balloons were tethered by cable to, usually, winches mounted on tenders, such as the Fordson Sussex, and their purpose was to hinder enemy aircraft and/or cause them to crash by collision with the cables or even the balloon itself. They were used in large clusters, effectively creating a blockade in the sky and sometimes with netting suspended beneath and between balloons. Barrage balloons were only mildly effective as many aircraft were capable of simply flying above them but they were a little more effective against the V1 Flying Bomb as these pilotless aircraft, powered by the Argus As 014 pulse-jet engine, flew on a predetermined course, set immediately prior to launch, and at a relatively lower altitude. Used by both the Axis and the Allies in both World Wars, the purpose of barrage balloons at Marchwood was to protect the docks and industry of Southampton. Unfortunately barrage balloons not only caused problems for enemy aircraft but also for our own. Marchwood's barrage balloons were in the charge of 930 Balloon Squadron, Southampton. In the early hours of 15 August 1940 Whitley Bomber P5044 of 77 Squadron collided with a balloon cable at the Bury Farm (Marchwood) site. The aircraft flew on over Southampton only to collided with another balloon cable, this time belonging to 924 Balloon Squadron, Eastleigh. The aircraft lost some 15ft of one wing, sliced off by one of other of the cables (precise details are not known but both cables would likely have inflicted damage) and crashed on the outskirts of Eastleigh killing all five crew members. Whitley P5044 was based at RAF Driffield (East Yorkshire) from where it took off at 19:35hrs the previous evening for a bombing raid on an oil depot at Bordeaux, France, and the crash occurred on its return. Thus as tragic as it was, fortunately there were no bombs on board. The crew were; F/O W.A. Stenhouse; F/O R.B. McGregor; Sgt C.L.G. Hood; Sgt J. Burrow; Sgt H. Davis. All were buried on 21 August 1940 at All Saints church, Fawley. The cause of the crash is said to have been due to the crew receiving incorrect information from control. The incident involving P5044 was by no means the only one involving friendly aircraft over home territory and the Luftwaffe had similar incidents over Germany.

The various Operations, including Overlord, which came to be known as 'The Normandy Landings', or 'D-Day', had their origins in a perhaps surprising location - Moscow. Joseph Stalin, Russian - Иосиф Сталин, had a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany which could be described at best as 'uneasy'. This pact came to an end on 22 June 1941 with Operation Barbarossa, the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union. In typical Hitler style, no notice was taken of his military commanders who knew virtually from the outset that the invasion would be a suicide mission for Germany. And so it was, Barbarossa ended in defeat for Germany at Stalingrad in late 1942. Casualties amounted to some six million which can be broken down to some five million Russians and one million Germans. As these figures indicate, it was not so much Stalin's military strength which defeated Germany but the Russian winter; cut off from supplies and woefully inadequately equipped for the extreme cold, the German forces literally starved and froze to death. Non aggression pacts are strange affairs which indicate neither any particular alliance nor any form of neutrality. The make-up of the Soviet Union was complex and it should be remembered the Germans continued to occupy, or collaborate with, various Soviet member states (the so-called Soviet Republics) and this situation continued until the end of the war. Insofar as Russia was concerned Stalin was to turn to the Allies and made a desperate plea for aid with supplies and equipment. This aid was the purpose of the well known Arctic Convoys which supplied Russia through her northern ports from the United States and Great Britain. While fighting was ongoing on the Eastern Front, Stalin urged the Allies to create a Western Front to help relieve his own by-then-depleted army. The theory, Stalin surmised, was that Germany would be unable to sustain fighting on two Fronts and this eventually proved correct as indeed had been the case in WWI. Across the Atlantic in Washington, President Roosevelt chose General Dwight D Eisenhower to lead the invasion with Britain giving the task of commanding ground forces to General Bernard Montgomery (or 'Monty' as he was known). The United States had been pressing Britain on the matter since 1942 and apparently while the Battle of Stalingrad was still ongoing. Britain, however, dithered and mainly because of the U-Boat threat. By June 1943 it was considered the U-Boat threat had subsided enough for supplies and equipment to be shipped across the Atlantic and so in November 1943 Britain finally agreed to the invasion. This was the birth of Operation Overlord, or 'D-Day', and the birth of Marchwood military port. The date of November 1943, mentioned above, is significant as on Sunday 28 November 1943 the Marchwood Military Railway opened to traffic. This suggests that although Britain agreed to the D-Day invasion that month, she had already decided to go ahead and was making preparations but was waiting for the opportune time - perhaps because of the aforementioned U-Boat threat (U-Boat means Unterseeboot in German, in English 'Undersea Boat', in other words 'submarine'). Whatever the truth it should be remembered that at times of urgency, such as wartime, construction projects were fulfilled rapidly and the Marchwood Military Railway would have been installed very quickly and especially as part of the track and its junction with the Fawley branch had been in existence since 1939. It should also be remembered that the port was originally a much simpler affair than it is today. The military railway also predated the completion of the port and would have been used for bringing in men and materials so 28 November 1943 appears to be the date both port and railway opened for military, as opposed to construction, traffic. Originally the port had just a single jetty, that known today as Mulberry Jetty and originally Deep Water jetty. It is 190m long and comprises Berths 1 & 2, maintained at 4m low water. Today it carries three railway tracks (believed two originally), can handle vessels of up to 8,000 tonnes GRT and has limited Ro-Ro (Roll on - Roll off) facilities. There is currently one Dolphin. As originally constructed facilities, other than the jetty, were an administration block, mess rooms, workshops, stores, locomotive shed, accommodation for officers and limited barrack accommodation for NCOs and ratings. The latter was to considerably expand in the decades following WWII. The Model Room was possibly also an original feature. A Model Room, in the military context, is used for training and instructional purposes but that at Marchwood seems to have spent much of its life used as a store for [possibly redundant] cargo handling equipment. It was demolished, along with other buildings, sometime around 1990. The port also has Gunwharf Jetty. This jetty is not rail served, is 117m long, contains Berths 5 & 6 maintained respectively at 4m and 3m low water. It is used for berthing landing craft and a range of smaller vessels. Adjacent to Gunwharf is a small vessel maintenance facility with a boat lift of 225 tonne capacity. Precisely when this jetty was constructed is unclear. The third and largest jetty is Falklands Jetty. This was built not for the Falklands conflict of 2 April - 14 June 1982 as often thought but subsequently in the light of experience gained from it. Falklands Jetty is 220m long, rail served (three tracks) and has two 32 tonne cranes capable of handling containers. The jetty contains Berths 3 & 4, both of which are maintained to 8m low water and can accept vessels up to 25,000 tonnes GRT. There are also Ro-Ro facilities capable of handling a number of ramp configurations. The maintaining of the berths at 8m means the approaches to the port also have been dredged to this depth. Falklands Jetty currently has two Dolphins. The work involved in upgrading the port following the Falklands Campaign cost £18 million. As well as Falklands Jetty the work also comprised new training facilities, improved security and the facilities for handling containers.

As with numerous other locations around Britain's coastline, the military port was a hive of activity from November 1943 with the Mulberry harbours and associated equipment for use on D-Day. Mulberries, floating bridges etc. are often said to have been British inventions and used only by the Allies this was arguably not the case. The Germans had developed similar equipment for use in Operation Sealion, the invasion of Britain, which Hitler 'postponed indefinitely' on 17 September 1940 and turned his attentions to the east. It seems the German equipment never progressed beyond the experimental stage. Some of the equipment was taken to Alderney, Channel Islands, where it could be seen long after the war ended until it was finally removed in 1978. Of course, pontoons, caissons and so forth had been around for a very long time but their adaption and application to the Mulberries beyond the experimental stage can indeed be credited to the British. Mulberry harbours were crucial for the initials stages of D-Day, the Normandy Landings, until such a time as the Allies could capture one of the French ports - a task expected to take three months. In the event, the first port captured was a long way from Normandy at Antwerp, Belgium, six months later. Mulberry was the codename given to the entire artificial harbour ensembles which comprised Pheonix (reinforced concrete caissons), Bombardons (floating outer breakwaters), Corncobs (static breakwaters), Spuds (pierheads), Whales (steel roadway sections), Beetles (pontoons, steel, Whales, for the support of). Of these, Corncobs were vessels taken to Normandy either under tow or under their own steam and then scuttled. The sheltered waters they collectively provided were known as Gooseberries. Five Gooseberries were created thus: Gooseberry 1 at Utah Beach, Gooseberry 2 at Omaha Beach, Gooseberry 3 at Gold Beach, Gooseberry 4 at Juno Beach, Gooseberry 5 at Sword Beach. A total of sixty vessels are thought to have been scuttled (deliberately sunk, usually via sea cocks) to this end. After the war many of these vessels were salvaged for scrap but the remains of others lie to this day, along with an array of other equipment, including tanks, on the seabed off the Normandy coast.

The Mulberry caissons were constructed of concrete by civil engineering contractors at numerous locations around the British Isles. To hide them from enemy aircraft they were designed to be sunk until required, this being done at Dungeness and Pagham. Raising them was achieved by compressed air (hence 'Phoenix', ie to rise again), after which they were towed across to Normandy. Two Mulberry harbours were required; Mulberry A (American, at Omaha Beach) and Mulberry B (British, at Gold Beach). Unfortunately the storms of 18/19 June 1944 seriously damaged Mulberry A and it was abandoned. Some components were salvaged for use with Mulberry B which, known as 'Port Winston', went on to do the job it was designed to do, unloading troops, vehicles and equipment. Phoenix caissons were used as breakwaters in conjunction with the Gooseberry block-ships.

Click here to continue

|

Home Page

Home Page