In the 21st century there are generations of people who do not remember the local gasworks or have never heard of the existence of such, so a little history is in order before we reach Shipston-on-Stour. At one time it was impossible to travel very far without seeing one, usually the first indication being the towering gasometer which structures were commonly referred to as 'gas holders'. Almost every town had a gasworks while major cities could have several; London for example had fifty though not all at the same time, perhaps the best known being the huge site at Beckton. Other gasworks could be found at surprisingly remote locations, supplying gas to scattered rural communities. There were other gasworks which did not produce a public supply, such as at asylums and major railway workshops with the latter typically being for carriage lighting and sometimes producing gas from oil rather than coal which was the usual raw material and that which we will focus upon here.

Coke

Coke is a type of smokeless fuel produced by baking coal in an oven free of oxygen. It can also be produced from oil and can also occur naturally when at some point in time coal deep underground has ignited, which can happen under certain conditions where large quantities exist. Self igniting fires in ships bunkers were, for example, not uncommon. Coke has been produced for centuries and at, in modern parlance, 'coke ovens' or 'coking plant' and is the fuel used by blast furnaces at steelworks. Early railway steam locomotives burned coke as a way around the stipulation in early 19th century Acts which required locomotives to "Consume their own smoke". The production of coke produces a number of by-products among which are ammonia, coal tar, benzene, naphthalene and coal gas. This is the principle of the gasworks, the major difference in simple terms being the intended end product.

William Murdoch

William Murdoch (1754 - 1839) was a chemist, inventor and mechanical engineer born in Lugar, Ayrshire. In 1777 Murdoch went, reputedly on foot, to Soho, Birmingham where he hoped to find employment with James Watt (Boulton & Watt, the steam engine builders) and to this end he was successful. Two years later Murdoch was sent to Redruth, Cornwall as a Senior Engine Erector. Boulton & Watt [beam] engines were used to pump water from the Cornish tin mines but in this era engines were erected, operated and maintained by the manufacturer and this was Murdoch's job. Payment to the engine builder was what we would today call 'Performance Related', which was good for the user of the engines but potentially precarious for the engine builder and for people like Murdoch. Nevertheless these relatively crude, given the technology of the time, engines were very successful.

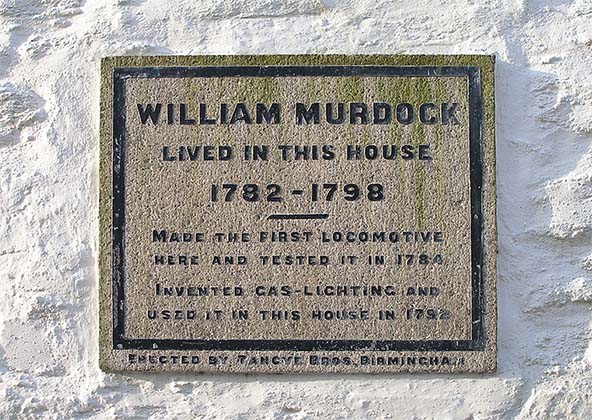

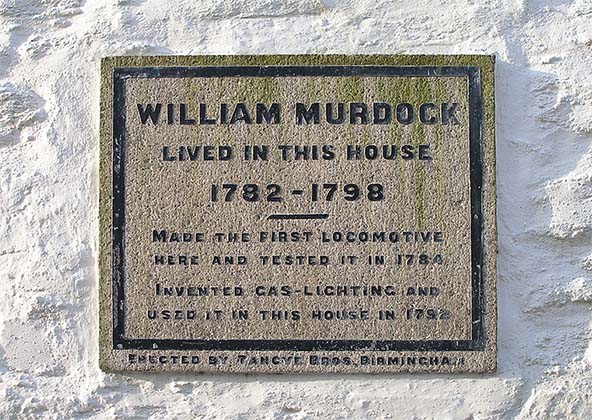

While in Redruth Murdoch began experimenting with gas lighting as a means of improving upon the lamps then in use which burned various oils and fats. He is often credited with being the inventor of gas lighting and although this is not strictly correct he can be credited with being the first in Britain to introduce the principle albeit in a very crude and small scale way. Murdoch's Redruth house is acknowledged as being the first in Britain to be illuminated by gas, in 1792, and the house now bears a plaque to that effect.

The plaque on Murdoch's Redruth house, photographed in 2007. Reproduced from Wikipedia under creative commons licence

Unfortunately there are a lot of unclear details concerning Murdoch and his work, one of which is the "Locomotive" mentioned on the plaque. It seemingly refers not to a railway locomotive, which in the 1790s were still in the future, but to a working model of a very simple steam-powered road vehicle. It is also unlikely the gas lighting was used only in the house in 1792, which is what the plaque implies. Murdoch returned to Birmingham in 1798 (but whether the journey was made on foot again is not known) and continued his experiments with gas while still employed by Boulton & Watt. In 1805 the Salford cotton mill of Messrs. Philips & Lee became the first factory to be illuminated by gas with an eventual total of no less than 904 burners. These burners were of the naked flame type, normal for the time, and quite how safe this was in an environment of airborne dust and fibres is open to question but as no incidents are known to have occurred the mill must have been very well ventilated. Murdoch's error was to not take out a patent on his gas lighting and some historians are minded to think this was advised against by Boulton & Watt for some reason. Whatever the reason it was a huge missed opportunity for Boulton & Watt who abandoned the gas business in 1814.

Murdoch did however receive some worthwhile recognition. He wrote a paper, "Account of the Application of Gas from Coal to Economical Purposes" which was presented to the Royal Society in 1808 and for which he was awarded the Rumford Gold Medal for "both the first idea of applying, and the first actual application of gas to economical purposes". The wording of this citation yields a clue regarding how Murdoch came to be accepted, not entirely correctly, as the inventor of gas lighting. The true inventor was one Jean-Pierre Minckelers, a Dutch - Belgian who had made practical the coal gasification process a decade or so before Murdoch. William Murdoch suffered ill health in later life and died on 15 November 1839. He rests at St Mary's Church, Handsworth, Birmingham having had what was for the time a long and industrious life.

The commercial production of Town Gas

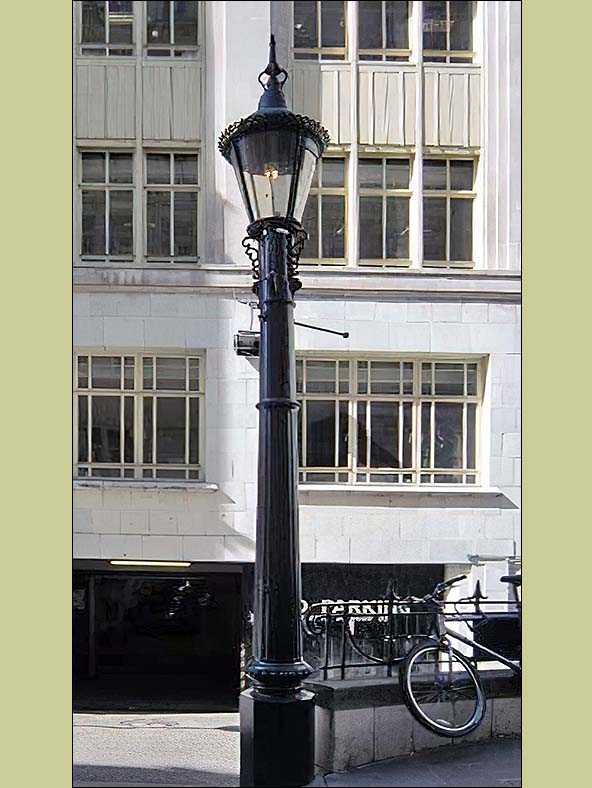

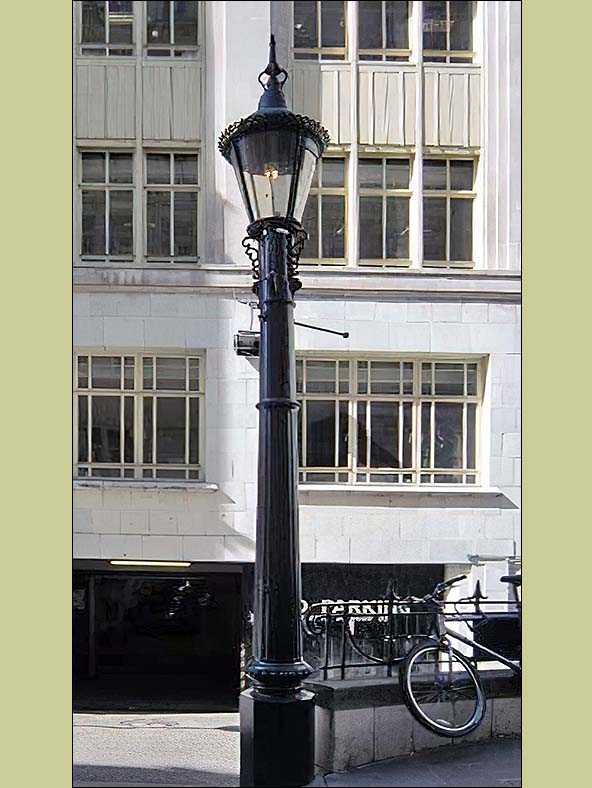

Coal gas, popularly referred to as "Town Gas", was an impure mix of gas comprising Hydrogen, Methane, Carbon Monoxide and Hydrogen Sulphide among traces of other things. Hydrogen Sulphide is the gas which gives an unpleasant 'rotten egg' odour to sewers and stagnant water and is the same gas which causes farts to smell. It is poisonous and flammable. To divert for a moment, there were once street lamps known as 'Gas Destructor Lamps' but commonly referred to as 'Fart Lamps' which burned gas drawn from sewers. Although very cheap to run, regulation of the gas supply was difficult and these lamps had a habit of extinguishing themselves only to then fill the air with a foul smell. Several of these Destructor Lamps still exist around the country, no longer operational and retained as historical relics. One, however, is still operational although due to being damaged by a road accident the present lamp is in fact a replica albeit a working replica. It stands on Carting Lane near London's Savoy Hotel and inevitably Carting Lane has come to be known by local people as "Farting Lane".

Town Gas was produced by the 'Destructive Gasification' process or 'Coal Gasification'. The process began in the gasworks Retort House, a Retort being a type of oven in which coal was baked in an oxygen-free oven, with fuel for the baking usually being coal. Once gas has been extracted from the baked coal, what remains is coke and there is the link with Coke Ovens as mentioned earlier. A Retort could be a small, single storey building or a massive towering structure charged from the top and with a railway track running beneath it. This latter was the reason for the squat and rather odd-looking steam locomotives used at major gasworks with internal railway systems such as Beckton.

The word 'Retort' has several meanings. It can mean a person-to-person rebuff while the proper name for a cremation furnace is 'Retort'. In the scientific sense retort means distillation hence why Town Gas was produced in a Retort, in other words producing or converting one substance into another substance or substances. Similarly cremation furnaces convert bodies into calcified remains which are then pulverised to leave what are commonly termed 'Ashes'.

Back at the gasworks, hot gas from the Retort passes to the condenser, the process of which separates out ammonia and tar, before passing to the scrubber which is usually in the form of a tower filled with coke and sprayed with water. This stage removes dust and any remaining traces of coke and tar. The next stage is the purifier which by means of iron oxide removes most of the Hydrogen Sulphide - this being the source of the 'rotten egg' smells which often pervaded in the area surrounding a gasworks. From here the gas is then fed to a Gasometer from which it is piped to consumers. A Gasometer, often called a 'Gas Holder', comprises a circular tank in the form of a deep dish containing water. Into this fits a 'Cap' or 'Lift' in the form of an inverted can. Imagine an empty, upright Baked Bean tin with another, smaller, upturned tin inside it. The water provides the seal between the two. As gas is pumped into the Gasometer the Cap rises and its weight provides the pressure in the mains supply, just above atmospheric pressure. Many Gasometers have telescopic multi-section caps and one such is shown below.

Photographed in October 2007, this Gasometer at Brampton, near Chesterfield, has a telescopic cap and is shown here in extended situation. It is very rusty; gasometers were usually painted all over in a light shade of grey as seen at the bottom. After the closing down of gasworks, these structures often remained for storage and pressurising of natural gas but by 2024 they were beginning to become rare. Some have been converted, rather controversially, into offices or residential accommodation but these examples have an external framework which is all that remains of the original structure. Photo by Alan Heardman and reproduced under Creative Commons Licence from Geograph

As noted, Town Gas was poisonous and some means of detection by smell was needed. This could be fulfilled by remaining traces of Hydrogen Sulphide or by adding Ethyl Mercaptan (aka Methanethiol) which is harmless but pungent gas. This is the same gas added to natural gas which is otherwise odourless. Unfortunately with Town Gas reliant only upon traces of Hydrogen Sulphide it was not always detectable by smell and accidental deaths were, while hardly a daily occurrence, were not exactly uncommon. There were also suicides which gave rise to the expression "stick your head in a gas oven" which was not meant literally but as a form of insult aimed at somebody who had caused an upset or some other sort of problem. Unlike today, gas appliances did not have safety devices which cut off the gas supply should the flame be extinguished for whatever reason, for example a temporary interruption to the supply.

The first gasworks for a public supply was located on the south side of Great Peter Street, Westminster between Marsham Street and Monck Street. It commenced operation in 1813 and closed in 1937. Part of its site is now occupied by The Home Office and other Government departments (The Home Office relocated from 102 Petty France, better known as 50 Queen Anne's Gate in 2004).

The Westminster Gasworks shown on the OS 1:1056 published in 1895. The Palace of Westminster and Westminster Bridge are just off the top of the map

This plaque can be seen on Great Peter Street. "Gas Light & Coke Company" or variations of it was a title used by the majority of public gas suppliers until the industry was nationalised in 1948. The full title was the "Chartered Gas Light & Coke Company" and it supplied gas for lighting to the Westminster and Southwark areas. Photo by Andrew Davidson and reproduced from Wikipedia under Creative Commons Licence

Gas lighting and coke was literally what these companies supplied initially but appliances soon appeared, for those who could afford them. Gas cookers, gas irons, gas refrigerators (why does that word not contain a 'd' yet the abbreviated version 'fridge' does?) and even gas wireless (radio) receivers could be had among numerous other items. The gas wireless used a thermocouple to generate electricity which then maintained the charge of an accumulator. There were also paraffin versions. Early gas lighting was unlike that which can still be seen today and which uses incandescent mantles. Instead burners were of the simple open flame type giving a yellowish flame little better than that of a wick oil lamp, but it was relatively cleaner and far more convenient. There were various types of open flame burner, of which perhaps the best known was the 'batwing' type.

In about 1860 a vastly improved form of gas lighting was installed on Westminster Bridge. Known as 'Drummond' lighting it worked by a gas flame on a piece of Calcium Hydroxide which the flame caused to glow a brilliant white. Calcium Hydroxide is better known as 'slaked lime' and these lamps came to be known as 'limelight'. It was the origin of the expression "in the limelight", meaning to give somebody or something exposure. These lamps worked well when they were working well. The problem was they required frequent maintenance, the slaked lime having a very limited life. Slaked lime also needs careful handling as it can cause burns, blistering skin and more serious health problems. Nevertheless the illuminating of Westminster Bridge in this manner was a wonder of its time and became something of what we would today call a tourist attraction. Unfortunately it was not to last and alternative, effective gas lighting had to await the invention of mantles in the late 19th century and perfection of same had to wait even longer.

The Shipston-on-Stour Gas Light & Coke Company

As mentioned, the "Gas Light & Coke" description was part of the title of the majority of companies supplying Town Gas and that at Shipston-on-Stour was no exception. The alternative title "The Shipston-on-Stour Gas Light, Coke & Coal Company" has also been seen and if correct then this company was also a coal merchant although Hutchings was for many years the coal merchant in the area.

The description given earlier outlining how a gasworks operated applies to Shipston-on-Stour so needs no repetition. 'Shipston Gasworks' as we will hereafter refer to it has a couple of enduring claims to fame; firstly it was reputedly the smallest gasworks in this country to supply the public and secondly it was operated by one man. The 'smallest' claim is very much open to question and indeed has been questioned a number of times as proof requires elaboration. Was the claim based upon physical size? Was it based upon production capacity? Was it based upon the number of consumers supplied? The answer may have to remain in the realms of 'whatever one wants to believe'.

Shipston Gasworks was not the only one to be operated, at least for part of its life, by one man. The gasworks at Goudhurst, Kent, was another example and operate in its final years by a Mr Arthur Fisher. From what little is known about it, Goudhurst Gasworks was possibly smaller than that at Shipston-on-Stour. Goudhurst Gasworks was located on the east side of North Road, about a three-quarter mile north of the village centre. Kent County Council says this gasworks existed from circa 1850 to circa 1960. It predated the existence of the Hawkhurst branch railway and was some distance from Goudhurst station, to the west of the village, and Pattenden Siding which was some distance south of the village. Probably, therefore, Goudhurst Gasworks received coal, initially at least, via the River Teise and thence by horse and cart.

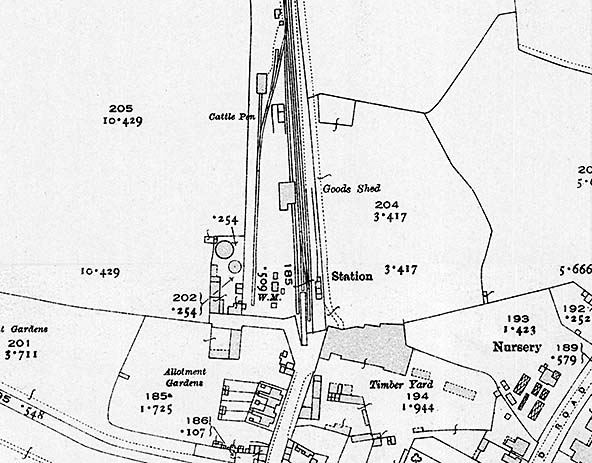

Shipston Gasworks suffered no such remoteness. The Stratford & Moreton Railway (the horse tramway) reached Shipston-on-Stour in 1836 and the gasworks commenced operation in 1848. It was not rail connected in the sense that a siding or sidings penetrated into the gasworks but it remained rail served, more or less, right up until Shipston-on-Stour station closed in 1960. "More or less" refers to periods when the horse tramway was effectively disused and when what became the Shipston-on-Stour branch was being rebuilt by the Oxford, Worcester & Wolverhampton and Great Western Railway companies. At these times coal would either have been delivered by road or the gasworks built up and used its coal stockpile. All gasworks, regardless of size, maintained coal stockpiles to ensure continuity of the gas supply during any interruptions to deliveries, although such stockpiles did not and could not last indefinitely. Upon closure of the railway to Shipston-on-Stour in 1960, between then and the 1963 closure of the gasworks coal was supplied by road from a Merchant at Moreton-in-Marsh.

Map scale is all important and this one, OS 6in published 1924, shows the gasworks buildings plus the two gasometers but no other detail. "Shipston Gas Co." is an abbreviation, quite common on maps of this period - if any annotation was included at all

This is an extract from the OS 25in map published 1923. The second gasometer is off the edge of the map but this scale shows the division of the buildings. In the bottom left corner of the site was the retort house and to its north was the scrubbing and condensing equipment; the condensing equipment would have been in the open air and in what appears to be a compound at the north-west corner of the site. In the bottom right corner of the site was and still is the manager's house and the small buildings to its north housed metering and other instruments. There was also a cashier's office where consumers would have gone to pay their gas bills but where this was located is unclear. Something of a 'real time' idea of the various buildings can be gleaned from the two films linked to at the end of this feature

This is an extract from the OS 25in map published 1923. The second gasometer is off the edge of the map but this scale shows the division of the buildings. In the bottom left corner of the site was the retort house and to its north was the scrubbing and condensing equipment; the condensing equipment would have been in the open air and in what appears to be a compound at the north-west corner of the site. In the bottom right corner of the site was and still is the manager's house and the small buildings to its north housed metering and other instruments. There was also a cashier's office where consumers would have gone to pay their gas bills but where this was located is unclear. Something of a 'real time' idea of the various buildings can be gleaned from the two films linked to at the end of this feature From 1930 the owner, manager and operator of Shipston Gasworks was Mr Dalton Charles Darnley and in a television interview (see links) Mr Darnley himself said he ran the gasworks single-handedly until Nationalisation in 1948. While there is no doubt Mr Darnley was very much a hands-on man it is difficult to see how he could have literally done everything and the same could be said of Mr Fisher at Goudhurst and other allegedly 'one man band' gasworks. If true Mr Darnley's work would have ranged from unloading tons of coal from railway wagons to dealing with people coming to pay their gas bills. In one, at least, of the films Mr Darnley described how at night he grabbed a couple of hours sleep, went to attend his gasworks, grabbed another couple of hours sleep and so on. Too much of that along with much hard, dirty, physical work could result in major health problems although as we will see it did Mr Darnley no harm. Again, there is no doubt Mr Darnley was a hands-on man but one has to suspect the story was somewhat embellished for the television articles. It might be wondered what happened if Mr Darnley became ill or had to leave the gasworks to attend a commitment elsewhere, let alone wonder who went around Shipston-on-Stour reading gas meters, attended to any faults such and so on. There must have been people who Mr Darnley could call upon when necessary, perhaps including his wife who may have acted as cashier and/or meter reader. Whatever the reality, the 'single handed' story has persisted and probably always will.

Depending upon source, Shipston Gasworks supplied between 134 and 150 consumers. The actual figure would have varied from time to time. Consumers were a mix of private, i.e. residential, and public. Photographs of Shipston-on-Stour show gas street lighting to have been present, although not exactly in adundance and the railway station was also gas lit. Some photographs, albeit dated only approximately, suggest electric street lighting had started to appear by or during the 1950s

In this probably deliberately posed photograph, presumably from 1963, Mr Darnley is seen checking the trace recording gas production volumes. The device would have been similar to the tracer of a Barograph. The large glass tube, fluid filled, on the left would have given a visual indication of pressure in the gasometer. Note the rather dubious-looking electric light hanging from the ceiling. It is not easy to determine what the group photograph on the wall actually depicts but it may have been the West Midlands Gas Board cricket team, which Mr Darnley once captained although the attire of those in the photograph does not suggest cricket. The sign on the right advises "Shillings available. Please ask the cashier". It is a reminder that some consumers used coin-in-the-slot prepayment meters. Prepayment meters of course still exist today although most no longer use coins and 'topping' up is done by electronic means at, for example, a local shop offering PayPoint. A coin meter can be seen, briefly, in the films linked to at the end of this feature

Photo from Roger Keddis collection

Britain's gas industry was nationalised in 1948 and Shipston Gasworks was taken over by the West Midlands Gas Board. Mr Darnley was retained as manager (there was no reason not to) and provided with an assistant. Mr Darnley was also able to call for additional help when necessary, this being one of the advantages of Nationalisation. This additional help would have been drawn from another gasworks in the Board's area such as Stratford-upon-Avon

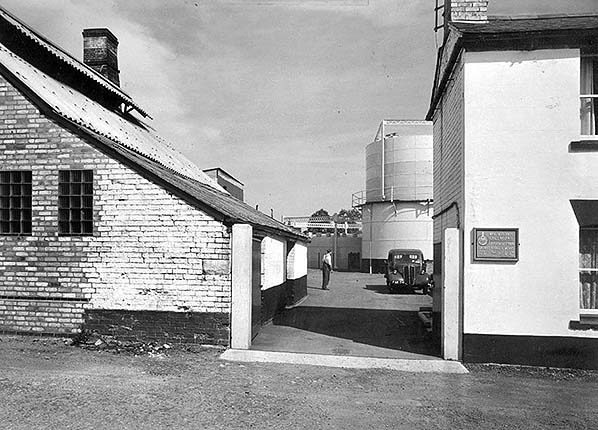

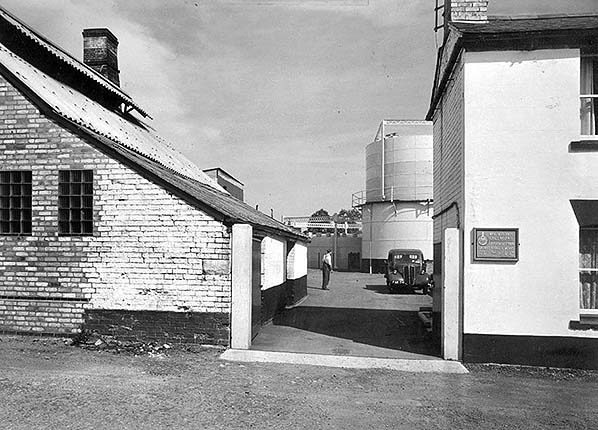

Shipston Gasworks looking in from Station Road sometime, the sign informs us, during West Midlands Gas Board days. The manager's house is on the right and the Retort house on the left. Gasworks invariably had more than one Retort and they were grouped together in what was known as a 'Battery'. Shipston Gasworks appears to have got by with a battery of just two Retorts and it has been remarked that a major city gasworks could produce the same amount of gas in one day than Shipston could in one year. Of the two gasometers seen here, that nearest the camera, which is charged with gas, was the original while that in the background, which is empty of gas, was a later addition. The concrete blocks on top of its Cap were to aid pressurisation - obviously this gasometer had a problem. Parked in the yard is a Fordson E83W pick-up as indicated by the protective bars over the rear windows of the cab. These vehicles, van and pick-up, were also marketed under "Ford Thames" branding. They were semi forward control and for some reason the engine was mounted toward the nearside (assuming right hand drive) and its cowling awkwardly occupied much of the passenger side foot well. The vehicle seen here was probably owned by the Gas Board

Photo from Roger Keddis collection

Similar to the electricity grid the Nationalised gas industry was to follow the same path by creating a gas grid. Gas and electricity each have their own advantages and while gas lighting has all-but disappeared from private residences and much public gas lighting has disappeared (a perhaps surprising amount still exists, especially in London) gas fired central heating has increased to the point of being not too far off universal so the use of gas in both domestic and industrial applications has by no means diminished into insignificance. Nevertheless the Nationalised gas industry set out, not unreasonably, to rid itself of many smaller gasworks which were dotted around all over the country and were barely viable. The West Midlands Gas Board hung onto Shipston Gasworks for fifteen years until it closed on 15 December 1963. Thereafter Shipston-on-Stour received its gas via pipeline from Stratford-upon-Avon. The pipeline was routed via Alderminster, Newbold and Tredington

The remains of Shipston-on-Stour Gasworks viewed from Station Road in 2023. The view faces north north-east and the railway station was off to the right as is the surviving weigh office. Station Road is fairly narrow and the frontage of the former gasworks quite wide, so the site is none too easy to photograph full on, hence the angle. Dominating the scene is the former manager's house and partly visible behind it are the small, single storey buildings thought to have contained an office and metering equipment. The wall at bottom left is all that remains of the former retort house and has been rendered. Comparing this with the earlier view above, it can be seen the two gateposts survive while on the left hand chimney stack the brackets for a television aerial are still there although the actual aerial is now UHF.

Photo by Margaret Cullen

Until Nationalisation Mr Darnley owned, as we have seen, the gasworks including the house. When the West MIdlands Gas Board took over, Mr Darnley would have done quite well out of it. He would have been compensated, in other words the gasworks was purchased from him and as employed manager thereafter he would have received a salary. As closure approached in 1963 Mr Darnley was quite upbeat about it and this is evident in the films produced for television. No doubt after many years of hard, dirty work he was looking forward to his free time to take part in local events and spend more time with his family. After closure it is known that Mr & Mrs Darnley continued to reside in the house on station road but whether ownership of the house was retained or if it was rented from the Gas Board is not known. It is thought that after gas production ceased Mr Darnley continued for a time producing and selling coke. This would have meant the Retorts continued to operate and therefore gas continued to be produced, presumably simply vented to atmosphere but details and indeed confirmation of this has proved to be another grey area.

Mr Darnley was commonly known as Dick Darnley but how this came about is not known. 'Dick' is usually a nickname given to people forenamed Richard. Mr Darnley was born at Purton, Gloucestershire on 23 July 1908 and in his interviews for television he displays a hint of the accent of that part of the country. In about November 1930 he married Ethel Annie Crane, born 28 April 1909 at Halesworth, Suffolk. The marriage is recorded as having taken place at Blything, Suffolk which was a Rural District of East Suffolk embracing the Halesworth and Southwold area. Blything RD was abolished on 31 March 1934 to be replaced by Blyth Rural District which itself became Suffolk Coastal in 1974. As if that wasn't enough, Suffolk Coastal merged with Waveney District in 2019 to form the district currently (2024) known simply and logically as East Suffolk. The marriage was recorded by the then Blything Rural District but the exact location was not known at the time of writing. In all probability, though, it was Halesworth. In at least one of the 1963 television interviews Mr Darnley stated he had been at Shipston-on-Stour for 33 years, in other words since 1930. It therefore appears likely Mr Darnley had already acquired the gasworks at the time of his marriage as the Darnley's were resident at Shipston-on-Stour immediately afterwards. Mr & Mrs Darnley both enjoyed very long lives. Mr Darnley died in July 2000, aged 92 and Mrs Darnley in May 2004, aged 95.

Apart from what is shown in the photograph above, the site of the gasworks became engulfed by modern housing following the general clearing of the area in the early 21st century.

Additional Notes

Electricity at Shipston-on-Stour

As we have seen all cities, most towns and even some villages had their own gasworks while cities and many towns also once had their own electricity generating stations. Shipston-on-Stour was among them. In July 1912 there was a demonstration of electrical power, as it was termed, but thereafter information is vague. In 1913 the "Shipston Electrical Company" was formed apparently to take over an existing electricity supply outfit and while this was probably that set up in 1912 this is unconfirmed. Whatever the background, the 1913 operation was taken over in 1916 by "The New Shipston Lighting Company" which had the stated intention of 'reconstructing the works' but what this actually meant is not known. Did it mean the 1913 works had been abandoned or did it mean it was still operational but required upgrading? We simply do not know. The generating station was located on Campden Road at its junction with Green Lane and in 2024 the site was occupied by a car wash and valet business. Electricity was generated at 100VDC with a capacity of 20kW which translates to 100 volts at 200 Amps, which was reasonably respectable for such a small generating station at the time but in practical terms was next to useless for a public supply, which was via overhead power lines through which, in addition to the feeble supply, there would have been voltage drop. The supply was actually from a bank of accumulators (wet cells similar in principle to a lead-acid vehicle battery) which were charged by a pair of dynamos driven by two gas engines, with a third engine as a standby. These engines ran off Producer Gas, generated on site from coke supplied by Shipston Gasworks. It might be wondered why gas was not simply piped from the gasworks but the likely answer to that would be cost of installing the pipeline. The electric lighting was apparently mainly on Sheep Street, in the centre of the town and not far from the generating station. In the event The New Shipston Lighting Company ceased trading in 1928 and that was the last that was heard of any electricity generating company in Shipston-on-Stour. The town then had to wait for the electricity National Grid to arrive. In 1925 a committee chaired by Lord Weir decided to create the Central Electricity Board with the aim of building a 'National Gridiron', a somewhat clumsy title which in 1935 became "The National Grid". It was born out the aftermath of the First World War. The Grid was constructed in 1936, on time and on budget although there were still some areas, mainly remote and isolated communities, which had to wait several more years for electricity to reach them. Strangely from the viewpoint of today there were also people, even in cities, who refused to be connected for various reasons and this persisted into the 1970s. The early generating stations, as Power Stations were once commonly called, could be owned privately or by local authorities, often starting out as private concerns before being taken over by Corporations.

Gas Nationalisation and Natural Gas

Nationalisation of the gas industry created twelve regional Gas Boards. Scotland and Wales had Boards with oversaw the entire countries but England was divided into ten Boards of which the boundaries were not always logical. The South Western Gas Board, for example, covered parts of Oxfordshire while the Eastern Gas Board penetrated well into London but outside of the one-time County of London (LCC) area. Tottenham Gasworks, to give an example, came under the Eastern Gas Board which predominantly covered East Anglia. Each of these regional boards were managed as separate entities despite being State owned and this system worked well. In the MACE film covering the impending closure of Shipston Gasworks can be seen a sign displaying the slogan "High Speed Gas", a campaign which began in 1962 Although there were issues with gas pressure where smaller gasworks were concerned, "High Speed Gas" was a marketing ploy used to manipulate the public into believing the replacing of local gasworks with piped-in supplies was a good thing which, generally speaking, it was.

Natural Gas (aka North Sea Gas) was first discovered in 1964 and began to be piped ashore in 1967 at Bacton, Norfolk. This sounded the death knell for what by then remained of the 'Town Gas' gasworks, the last one being at Muirkirk, Scotland which stank out the local area for the last time in 1977. Natural Gas required a new pipeline grid system due to the offshore nature of the supply but generally these new pipelines linked into the existing gas grid. In many cases gasometers which had previously held Town Gas were used to store and pressurise Natural Gas and some continue in this role in the 21st century although the numbers are diminishing as modern plant takes over the role. Natural Gas consists largely of Methane, which is odourless and non poisonous but when burned does produce Carbon Monoxide as indeed does the burning of many fuels.

The British people have a tendency to resist change and this became apparent during the changeover to Natural Gas with people being suspicious of both the new gas and of it all being some sort of financial con among other things. The "High Speed Gas" slogan remained current and was now used to promote Natural Gas. To this end there were endless media campaigns, especially on television with which a range of advertisements were run of which some were quite pathetic and insulted the intelligence of viewers. Others, though, took on something of a comedy stance and some were quite sensible and informative. "High Speed" had little to do with the gas however and advertisements tended to focus upon new gas appliances, for example showing a housewife with an old, dirty gas cooker which had to be lit using matches and then showing a comparison with a brand spanking new cooker with piezo ignition. Scoff at these now-old advertisements we may well do but the advertising campaign was a success - after all, that was of course the intention. One problem was the need to convert existing gas appliances to burn Natural Gas, or rather to burn it efficiently; the reason was Natural Gas producing roughly double the BTUs (British Thermal Units) of Town Gas. The conversion work was carried out by engineers visiting people's homes and industry and was done at no cost to the consumer. It was a model of efficiency which Britain has rarely seen the likes of since. One problem was Natural Gas being odourless and therefore undetectable by smell. This was overcome be adding Mercaptan, mentioned earlier, to the gas giving it an odour similar to that of Town Gas.

Stratford-upon-Avon Gasworks

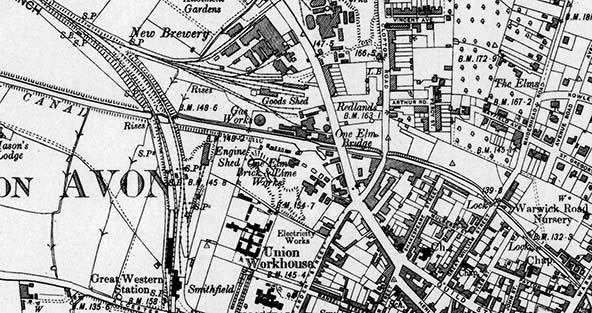

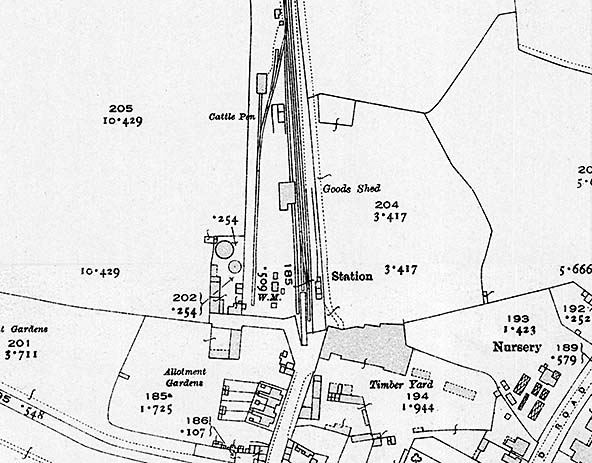

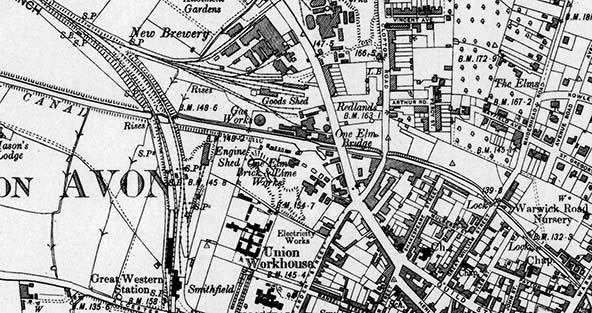

The original gasworks at Stratford-upon-Avon was located on Chapel Lane; opened in 1834 it closed in 1837 to be replaced by a new works in a location which came to be known as - and still is - "One Elm". The official name for this gasworks seems to have been "Timothy's Bridge Gas Works". The Stratford Gas Company's licence expired in 1880 but the town opposed its renewal, the outcome being the takeover by the Corporation as the "Stratford Corporation Gas Department". The gasworks stood on the west side of Birmingham Road on land between the Stratford Canal and what was the Birmingham Road terminus station of the Stratford-on-Avon Railway branch from Hatton. This station lasted for less than a year, thereafter becoming a goods depot. The gasworks, which was rail connected, was, in addition, close to One Elm Bridge, the origin of the "One Elm" name.

The OS 6 inch map published in 1922 shows Stratford-upon-Avon's so called 'One Elm' gasworks, immediately north of which is the original Birmingham Road railway station which by 1922 had long since been relegated to a goods depot. The 'Great Western Station' is that still in use today. The original gasworks in Chapel Lane is off the map at bottom right. It was close to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre and not far from the former Stratford & Moreton Railway wharf

Stratford-upon-Avon's 'One Elm' gasworks ceased production at round the same time as that at Shipston-on-Stour and like many such gasworks it became a storage facility for gas piped from elsewhere, initially Town Gas and then Natural Gas being still in use for this purpose in the late 1970s. What this tells us is that the gas pipelined to Shipston-on-Stour was not produced at Stratford-upon-Avon but piped from elsewhere via the storage facility at the latter.

Sources and further reading:

- https://www.oldmapsonline.org/

- https://warwickshireias.org/shipston-on-stour-power-report/

- City of Westminster, Westminster Libraries https://wcclibraries.wordpress.com/2015/08/31/the-gas-light-and-coke-company-in-westminster/

- https://theconversation.com/brighter-lives-are-lived-by-gas-how-natural-gas-was-sold-to-a-sceptical-public-in-post-war-britain-191633

- National Grid https://www.nationalgrid.com/about-us/what-we-do/our-history/history-electricity-britain

- https://www.findmypast.co.uk/

- University of Leicester, Special Collections Online

- The National Archives

- Health and Safety Executive

- Worcester News

In 1963 the BBC and ATV (Associated Television) recorded news articles about the pending closure of Shipston Gasworks.

Unfortunately the BBC version is spoiled by captions added subsequently, with which it is wrongly implied Dr Beeching was behind the closure of the Shipston-on-Stour branch. Only one complete gasworks now survives in Britain. Non operational, it has been restored as a museum. Located in Fakenham, Norfolk it is close to the remains of the former Fakenham West (formerly Fakenham Town) railway station. The museum is well worth a visit but the limited opening times should be noted.

Although not relevant to Shipston-on-Stour, some gasworks has their gasometers hidden within ornate brick structures and one such was at Warwick. What remains can be seen at Similar but far more ornate structures can be seen in Vienna, Austria The latter are seemingly the inspiration for what are known as 'The King's Cross Gasholders' and 'Gasometer Park' . These are the gasometers which famously could be seen from trains departing and arriving St Pancras, appearing in countless photographs.

This is an extract from the OS 25in map published 1923. The second gasometer is off the edge of the map but this scale shows the division of the buildings. In the bottom left corner of the site was the retort house and to its north was the scrubbing and condensing equipment; the condensing equipment would have been in the open air and in what appears to be a compound at the north-west corner of the site. In the bottom right corner of the site was and still is the manager's house and the small buildings to its north housed metering and other instruments. There was also a cashier's office where consumers would have gone to pay their gas bills but where this was located is unclear. Something of a 'real time' idea of the various buildings can be gleaned from the two films linked to at the end of this feature

This is an extract from the OS 25in map published 1923. The second gasometer is off the edge of the map but this scale shows the division of the buildings. In the bottom left corner of the site was the retort house and to its north was the scrubbing and condensing equipment; the condensing equipment would have been in the open air and in what appears to be a compound at the north-west corner of the site. In the bottom right corner of the site was and still is the manager's house and the small buildings to its north housed metering and other instruments. There was also a cashier's office where consumers would have gone to pay their gas bills but where this was located is unclear. Something of a 'real time' idea of the various buildings can be gleaned from the two films linked to at the end of this feature

Home Page

Home Page