Part 1: Eastern Counties Railway and early Great Eastern Railway years

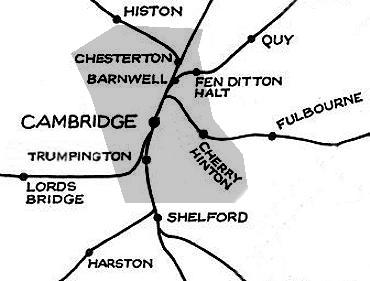

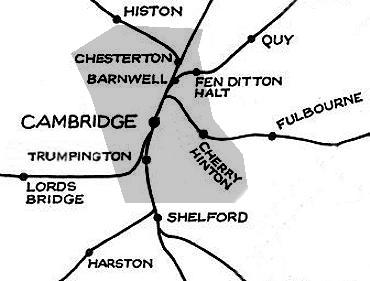

The present (2015) Cambridge station is the only still-open survivor of several which once served the City of Cambridge if we are to consider the city by its 21st century boundaries. The others were Barnwell Junction; Chesterton; Cherry Hinton; Fen Ditton Halt and Trumpington. The latter was a temporary station located on the London line immediately north of Long Road which, incidentally, was at that time crossed by means of a level crossing.  Trumpington station existed during 1922 to serve the Royal Show and a photograph of it appears in Part 2. Other stations, some still open and some not, are / were located just outside the present city boundary; Shelford, Fulbourne; Histon; Quy; Waterbeach and Harston. Of those, only Shelford and Waterbeach remain open.

Trumpington station existed during 1922 to serve the Royal Show and a photograph of it appears in Part 2. Other stations, some still open and some not, are / were located just outside the present city boundary; Shelford, Fulbourne; Histon; Quy; Waterbeach and Harston. Of those, only Shelford and Waterbeach remain open.

Chesterton station opened and closed in 1850 but will be reborn when the currently-under-construction Cambridge Science Park station, to quote its proposed name, opens.

The simplified map above shows the stations which have existed in the Cambridge area at various times. The shaded area represents very approximately the present-day Cambridge city boundary.

The building of the line

The first serious proposal for a railway serving Cambridge dates back to 1821 when one William James is reputed to have got as far as surveying a possible route from Bishops Stortford to Clayhithe Sluice*. In 1825 another proposal appeared, this time from London Bridge via Ware and Cambridge to, of all seemingly unlikely places, Cromford in Derbyshire; the plan was to reach Manchester via the High Peak Railway (better known today as the Cromford & High Peak Railway) and Stockport. This was not as absurd as it may seem; the line, had it been built, would have tapped into the industrial north-west and the quarrying activities of Derbyshire.

*Clayhithe is situated on the Cambridge - Horningsea - Waterbeach road at the point where the road crosses the River Cam and very close to Waterbeach station. In the 19th century, Clayhithe was busy with commercial river traffic.

The Clayhithe railway was intended to replace a proposed canal but in the event neither canal or railway were ever built. The Cromford scheme failed, it is said, simply because it was far too ambitious for its time.

The first railway built to Cambridge was that known today as the West Anglia route, albeit initially differing at the London end in respect of termini and precise routes within London. It was - and still is - a meandering and somewhat leisurely south - north route, with a section in the Harlow area actually running in a roughly east - west direction. It is today 55m 52ch from Liverpool Street via Hackney Downs and Tottenham Hale, against a point-to-point distance of some 45 miles, with some trains operating to, or via, Stratford and others operating via Seven Sisters.

In 1842 the Northern & Eastern Railway had opened its route from Stratford to Bishops Stortford, having previously reached Broxbourne in 1840, with powers to extend northward to Newport (the station prior to what is today Audley End) and thus a mere 16 miles short of Cambridge. Among several proposals for a railway between London and Cambridge was a route via Ware, Buntingford and Barkway but this was not to be, although from 1863 Buntingford did become the terminus of a branch from St Margarets on the Hertford (now Hertford East) branch. This proposal for a route to Cambridge via Ware was separate to that of the proposed Cromford route. The repeated mentions of Ware in the context of proposed routes to Cambridge seem to have come about for topographical reasons (Ware is in the Lea Valley) rather than for any importance attached to Ware itself or its location on what are now the A10 and A414 roads.

Other proposals for a railway to Cambridge included one via Loughton, Dunmow and Saffron Walden with a branch from the latter to Norwich. This, had it been built, would almost certainly have followed, at least in part, the course of what is today the eastern section of London Underground's Central Line. In the event, this route did not open until 1856 to Loughton (by the ECR) and to Epping and Ongar in 1865 (by the GER) while Dunmow and Saffron Walden were later to be served by branch lines; Bishops Stortford - Braintree and Audley End - Bartlow respectively.

Yet another scheme which came to nothing was the so-called 'Cambridge Transverse Railway'. This line was to have approached Cambridge from Bury and Newmarket before continuing to St Ives, Huntingdon and onwards to Market Harborough. This was a rather strange scheme in that the line was to skirt around the north side of Cambridge and the route it would have taken is known; from Cherry Hinton towards Barnwell, across the River Cam and across the Ely Road (now the A10). Thereafter the route was to cross Huntingdon Road (now the A14) but in doing so it becomes difficult to see how the line could have served St Ives. No details are known of any proposed sites for a station serving Cambridge and if there was to have been a station its siting would have been most inconvenient.

Powers for the Northern & Eastern (N&E) to build a railway to Cambridge were obtained by an Act of 4 July 1836 with a share capital of £1,200,000 with Michael Borthwick as engineer and, in 1837, David Macintosh was appointed as contractor but the economic situation at the time meant the scheme was scaled back to Broxbourne. The question of a London terminus was a somewhat dithery one; initial plans for an Islington terminus (the actual location was planned for a point on Kingsland Road; a lengthy road running north-south and which today is part of the A10) came to nothing, as did a plan to use Fenchurch Street station by agreement with the Commercial Railway, later renamed the London & Blackwall Railway.

While this dithering was ongoing, construction had begun from the Broxbourne end. The N&E then reached agreement with the Eastern Counties Railway (ECR) to use the latter's Stratford station and thence to Shoreditch. The N&E built the necessary link from Tottenham to Stratford (the present-day route via Lea Bridge) with dedicated platforms at the latter. To this day these platforms, 11 and 12, are known as the 'Cambridge Platforms'. The ECR agreed to build a separate station for the N&E at Shoreditch but in effect this amounted to nothing more than extra, dedicated platforms within the existing station as a result of, apparently, legal problems. This arrangement suited the ECR as it provided funds for projects elsewhere along its main line.

However, during 1837 things had become rather less rosy and the planned extension from Broxbourne to Bishops Stortford was abandoned by Act, as was the plan for an Islington terminus which, with hindsight, was just as well. Contractor problems also abounded; Borthwick continued as resident engineer, with Robert Stephenson appointed in the capacity of engineering consultant and George Parker Bidder appointed as contractor.

Later in 1837 the Bishops Stortford extension plan was fired-up once again. Messrs Grissell & Peto were appointed contractors and construction of the Stratford Tottenham link was finally started in March 1840. As we have seen, the Stratford - Broxbourne section opened on 15 September 1840. Initially single track, the line was quickly doubled. Apart from a ticket revenue dispute between the N&E and ECR concerning the Stratford - Shoreditch section, things apparently went relatively smoothly from then on.

The next stage was the extension from Broxbourne to Burnt Mill (Harlow) with Messrs Thornton as the contractor but in the event Messrs Grissell & Peto assumed responsibility. One year later, Messrs Earl and Pearce were appointed as contractors for the Burnt Mill - Bishops Stortford section. At this point it would appear our old friends Messrs Grissell & Peto came to assume overall responsibility for the entire line. The line as far as Bishops Stortford opened on 16 May 1842, while on 1 January 1844 the N&E became part of the ECR under a lease agreement. Notwithstanding this, the N&E continued to exist legally until as late as 1902 when it finally merged with by-then forty-year-old Great Eastern Railway. Meanwhile, up in Norfolk, the Norwich & Brandon Railway, soon to renamed Norfolk Railway, was busy with its line from Norwich (Trowse) to Brandon.

1850 Timetable

1850 Timetable

Cambridge University and the Railway

It is human nature to love a good myth, not least when it comes to the siting of Cambridge station. Whilst it is true the ECR, plus others, wished to build a station in the centre of Cambridge and it is also true the university were very reluctant to sell land to the ECR, it appears to be a myth that the university forbade the railway to encroach upon the centre of Cambridge in principle. The true reason for the station being sited one mile from the centre most likely lies in the fact the area to the west of what became the station site was already too densely built-up and the cost of a centrally-sited station was thus prohibitive.

What is not widely known is that there were no less than seventeen proposed sites for a station in Cambridge in the period up to 1864. The majority of these were in the south-western area of Cambridge and would have been no more convenient than the present station. Other sites were proposed at Gonville Place, on the site of the former gaol (prison), now Queen Ann Terrace; another at the junction of Castle Street and Northampton Street; another at the junction of Huntingdon Road and Victoria Road (at the top of the steep hill of Castle Street); another on Midsummer Common, just west of the present-day Elizabeth Way bridge. The most convenient proposals, for the city centre, would have been two proposed sites at or near Silver Street or another on a rather cramped site in the area bounded by Emmanuel Road, Parker Street, Clarendon Street and Orchard Street. The latter would have been close to the present New Square and Drummer Street bus station. It is known that this particular line would have branched off near Mill Road bridge and ran almost entirely in a cutting.

There was another, rather strange, proposal by the GER in 1863. On this occasion the university refused to sell land on Jesus Green (a park in the centre of Cambridge; many such open spaces in the city being owned by the university). However, the surviving record is a little unclear as it refers to a 'tram-road from the station to the River Cam'. Quite what was meant by 'tram-road' we do not know but the term is usually taken to mean an industrial line. With the passage of time this scheme has become muddled by various authors with a scheme for a 'tram-road' branching off south of Hills Road bridge [presumably at a junction trailing in the down direction] and ending at Coe Fen; an area of meadows near Peterhouse on the south-west fringe of the city centre. It is known that this line, had it been built, would have been operated as a shuttle service. It was one of the schemes which is known to have been blocked by the university.

For many decades there has been numerous luke-warm suggestions for the city centre to be served by a line entirely in tunnel but, of course, none have progressed into reality due, in part, to university objections.

Had any of these schemes become reality, it appears the present Cambridge station would have been named Cambridge General with any other station in or nearer the city centre being Cambridge Central.

The university placed what today would be considered outrageous restrictions upon the use of the railway by its students. The university was concerned about students slipping off to London by train and, whilst there, getting up to all manner of activities not deemed in-keeping with the university's image. The railway company could, for example, be fined for allowing students to travel, even if a ticket had been purchased. In practice, however, it would appear these restrictions were largely ignored.

Further, the university also placed restrictions, apparently by Act, on Sunday train services between 10am and 3pm. In his book The Great Eastern Railway Cecil J. Allen implies this restriction applied only to the Newmarket Railway, which reached Cambridge in 1851. Other sources state the restriction applied between 10am and 5pm and applied to all train services from the outset. The latter scenario is the most likely; if so the restriction in the Newmarket Railway Act would have merely been to ensure compliance.

In any event, Sunday services on the early railways were usually sparse - if any ran at all. We must remember that until relatively recent times, Sunday was very much a religious and family day, with most people complying. When people did travel on Sundays it was usually to visit relatives or for the occasional excursion. Shopping, public sporting fixtures and so on were unheard of on Sundays until well into the 20th century.

In 1886 and 1893 proposals to rebuild the operationally hopeless station into a more conventional layout were put forward, but these were blocked by, mainly, the university but also by the people of Cambridge. As we will later see, the university also hindered development of the Cambridge tramway as well as proving to be something of an obstacle in respect of the Newmarket line.

It has never been decisively explained why the university was seemingly so against the railway but we have to remember two things; a) In Victorian times and for centuries previously Cambridge very much was the university and up to a point still is and b) Victorian Britain revolved around status and class and this was especially so in southern England. Although the fare structure to a degree controlled who travelled and when, the middle and upper classes felt threatened by the perception of transport for the masses shattering what they saw as their solid, established high-society world by the influx of lower class 'riff raff'. Possibly the best example of the class system and the railways can be found in the fascinating story of the London Necropolis Company and its funeral trains to Brookwood Cemetery.

Not everybody was inconvenienced by the location of Cambridge station. Over the years buses, trams and cab drivers as well as traders along the way did a roaring trade. In time, the urban sprawl of Cambridge spread north-east, east and south-east from the railway plus in the 1960s Addenbrooke's Hospital was relocated to the south-west corner of the city. This has meant the inconvenient siting of the railway station has now become somewhat academic.

The gauge issue

What we know today as Standard Gauge, 4ft 8½ins, was by no means standard during the first half of the nineteenth century although it was rapidly becoming so. The ECR had opted for what we would today class as a Broad Gauge, specifically, 5ft, and the N&E had, for obvious reasons, also opted for the 5ft gauge. What remains unclear is when precisely the decision was taken to link-up with the Norfolk Railway at Brandon, bearing in mind the original desire was to reach York via Peterborough*. If this was prior to the decision to convert the ECR to standard gauge, the question must be asked of what the arrangements would have been at Brandon where the differing gauges would have met.

It appears the change of ECR gauge was largely as a result of Stephenson's advice to the ECR's John Braithwaite. The conversion began on 5 September 1844, with Stephenson superintending, and conversion of track, locomotives and rolling stock was completed on 7 October 1844. This was a remarkable achievement for the time, especially when considering the work progressed without disruption to traffic other than on the Hertford branch.

On 4 June 1844 Royal Assent had been given to build the railway north of Newport. Given this date, the dates given in the previous paragraph and when considering construction trains by necessity would have ran from the London end, the suggestion is that the 5ft gauge might well have extended north of Bishops Stortford before conversion was decided upon.

*This was the Great Northern Railway that never was; a very early scheme to link London and York via Cambridge, Peterborough and Lincoln. The intended name had no connection whatsoever with the 'real', Great Northern Railway. Following the (in)famous George Hudson becoming ECR chairman in 1845 the scheme was half-heartedly and unsuccessfully revived again. Many years later a Liverpool Street - York service did materialise, operating via the GN&GE Joint Line and Doncaster. Following the coming of the diesels and until 1982, this was reduced to a DMU service commencing at Cambridge and running via March and Spalding to either Doncaster or Sheffield.

The track of the Eastern Counties Railway

To follow on from the gauge subject, a mention of the ECR track may be of interest. In the first half of the 19th century many different types of track were in use and the ECR was one of a small number of companies which used a peculiar, even for the time, type of track. This track consisted of 'I' section rail which sat in 'V' section cast iron troughs, with the rails secured therein by means of wooden wedges. The troughs were fastened to either longitudinal sleepers or sleeper blocks (it is unclear which) and gauge was maintained by transverse tie-bars. This system would have been expensive, heavy and a maintenance liability. The arrangements for points and crossings with this type of track are not known.

What is known as 'Bullhead' rail, a type still in use today, did not become common until the second half of the 19th century. However, as early as November 1841 the ECR directors were considering the purchase of bullhead rail, to be delivered from South Wales to the Thames (meaning, it was to be delivered by sea).

Nothing further was apparently decided until the following appeared in the ECR minutes 'Rails for Newport extension; 75lb per yard, 4 chairs and sleepers per rail ie 2 sleepers 5ft apart and 2 at 2½ft apart' In trying to do the maths, the stated sleeper spacings appear rather odd, as does the number of sleepers and chairs per rail but the overall suggestion is that the type of track described above had been superceded by a type more resembling of railway track as we know it today. The emerging standard of that time was of the bullhead type but in very short lengths, with rail joints directly supported by cast iron chairs and with transverse sleepers maintaining the gauge. This is very likely to have been the type of track laid initially to and through Cambridge. Longer rail lengths were not practical until the introduction of steel rails; this did not occur until 1857 when the first such rails were laid a long way from Cambridge, at Derby.

A later minute, from 3 June 1847, notes that '4 chairs and sleepers per yard of 75lb rail' was an error and that the correct number should be five. Instructions to remedy this were issued but it is not clear if any work was actually undertaken. However, the reference to per yard of 75lb rail is possibly a grammatical error and actually refers to the weight of rail per yard rather than sleepers per yard.

The early years of Cambridge station and the island platform

The entire route between Bishops Stortford and Norwich opened on 30 July 1845. This was despite problems with landslips south of Cambridge and problems north of Cambridge where the line passed through the Fens (which were then much wetter than today). Many years later, the same problems on the Fenland section were to ultimately result in the construction of the Cambridge - Mildenhall branch.

The opening date had originally been planned for 1 July but on 8 July it was recorded that postponement was due to subsidence of the track.

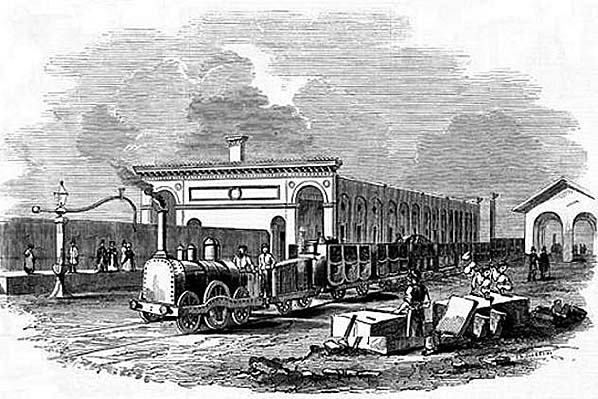

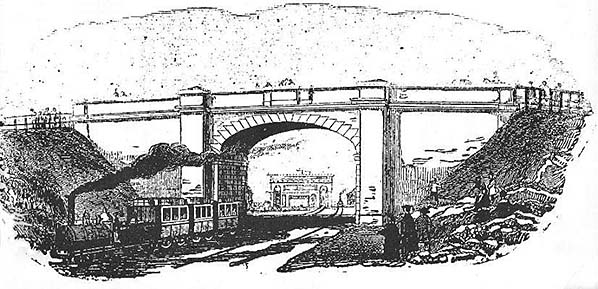

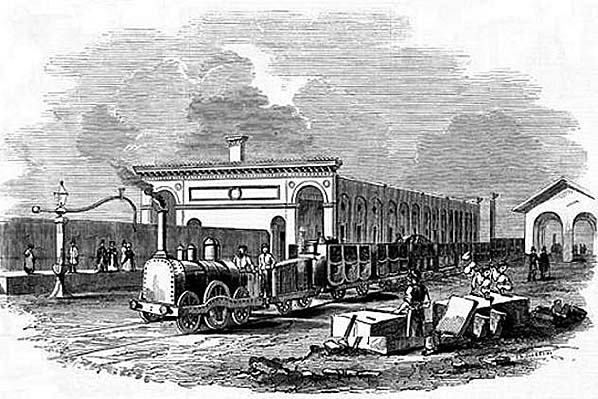

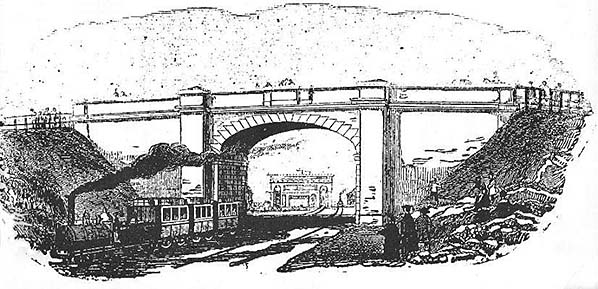

The above engraving is well known and appears in a large number of publications. It is one of a few known survivors from the time, another being a view of the station frontage from what later became the site of the flour mill. Another engraving shows the station from the south side of Hills Road bridge, with the bridge depicted as a rather ornate arched structure as seen below. The view above is looking north from the approximate site of where the 1926 Cambridge South signal box would stand. On the right the original locomotive shed can be seen; a two-road affair constructed by the ECR. Inside the shed another locomotive can be seen. The shed had a water tank for the locomotives, but precisely how this tank was incorporated is unclear.

Above is the view of the station from south of the original Hills Road bridge. The track running into the colonnade can be seen. There is some artistic licence in these engravings, but nevertheless we are provided with a valuable insight into what Cambridge station originally looked like. Of note is the attention given to details of buildings and other structures, which we can take as being quite accurate, while details of the trains tend to be quite comical.

Responsibility for the design of the station seems to have been a joint effort between Francis Thompson and Sancton Wood, while the building contractor was the well known, at the time, William Jackson. Later, the local firm of Joseph Peck & Sons, who were based on Coronation Street, undertook many of the subsequent alterations to the station.

The Italianate style of the station building will be noted and as subsequent events tend to indicate, more thought was given to appearance than to practicalities. The colonnade along the front of the building remains to this day, albeit now enclosed, while that on the platform side was short lived. Originally there was only one platform, i.e. no bays. Its original length is unclear. The station building was originally 190ft long and the original platform may have been confined to that length but extended beyond the colonnade as part of the alterations immediately prior to opening. Platform sections extending beyond the building were accessed via the smaller secondary arches at each end. The third engraving mentioned above shows the track running into the colonnade. We are unfortunately faced with a problem regarding the finer details of the Cambridge station of 1845, because the deposited plans (meaning, plans deposited with parliament) differ to the actual layout of the station at opening.

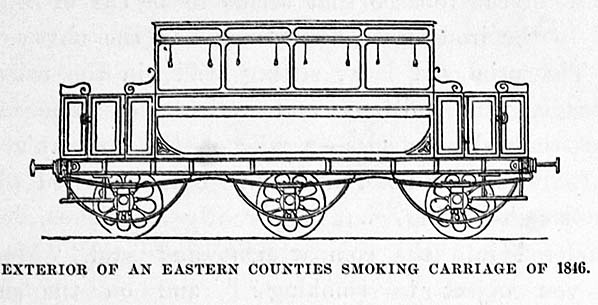

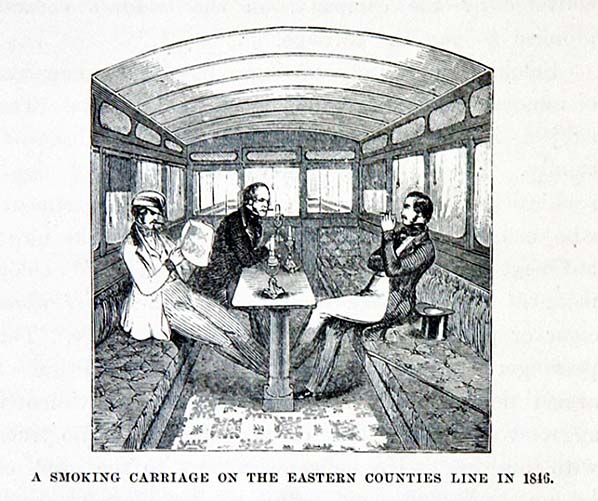

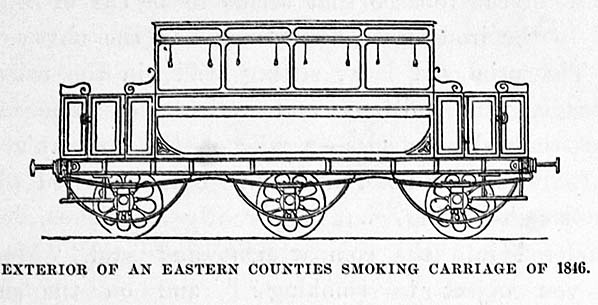

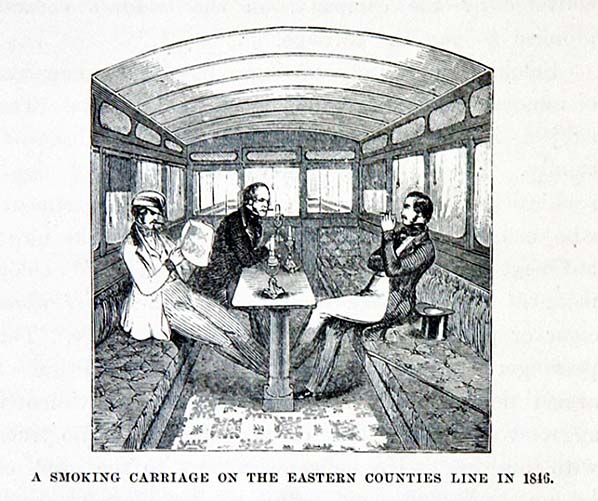

It should be remembered that the trains of the early 19th century were much smaller than those of today, so the thought of these early trains passing through the colonnade at Cambridge station is not so ridiculous as it may at first appear. An original ECR carriage, albeit dating from 1851, can be seen in the National Railway Museum. This and other surviving period vehicles, plus replicas, exemplify the relatively small size of early railway vehicles.

We do know the original platform at Cambridge quickly proved to be far too narrow and action was taken to remedy this at an early stage. It is recorded that on 3 June 1847, barely two years after the station opened, that £10,000 was to be spent on alterations. Between that date and 1850 a number of other payments were approved for station alterations.

The 1847 - 1850 period is significant for it was during that time the engine shed behind what is today Platform 6 was first built; the year was 1847 but the precise date is unknown. Originally a 4-road shed, it was expanded over the years and survived in use until 18 June 1962, but which time it had been coded 31A.

Sometime prior to 1849 a wooden island platform was built; partly as a result of the opening of the lines from Ely to Peterborough on 14 January 1847 and from St. Ives and Huntingdon on 17 August 1847 bringing additional traffic. Surviving plans from as early as the late 1845 show the island platform, but it probably did not appear until 1847. Details of the alterations costing £10,000 are not specific enough in the surviving records but the quoted costs would almost certainly have included the island platform, the necessary track alterations and possibly the new engine shed. In those days £10,000 was a very large sum of money, so the alterations were certainly not of a minor nature.

Little is known about this island platform, other than it being small, woefully inadequate and serving up trains only. It was replaced in 1850 by a second island platform, again of wood but much more substantial and a little more is known about this one. With the opening of the second island platform, the original platform beneath the colonnade was relegated to parcels and goods use. Passenger access to the island platform which, of course, served both up and down trains, was via a footbridge which was a persistent source of complaints due to its steep steps (the first island platform was accessed simply by walking across the tracks). Luggage was sent to and from the second island platform via a subway. The public were not permitted to use this subway, which is said to have been narrow and with a low headroom. It was also prone to flooding.

As already mentioned, the second engine shed at Cambridge had opened in 1847. Despite some sources suggesting the original shed survived until 1863, the records of the Eastern Counties Railway state it was demolished in December 1859.

Records for the year 1859, incidentally, contain the first mention of a bookstall at Cambridge station and it was, then, located inside the first class waiting room. Public rooms within the station building were, irrespective of class, also ornately finished in a style complementing the exterior of the building.

The island platform remained in use until, it is generally accepted, 1863*. The subway remained but was sealed off. With the demise of the island platform, the original platform was brought back into passenger use, but in widened form. This had involved the removal of the colonnade and consequent remodelling of the platform side of the station building. Since producing the first draft for this feature, a record has come to light stating the subway [actually referred to in this instance as the 'goods tunnel'] was taken out of use at the same time the original locomotive shed was demolished in December 1859. Ironically, in May 1859 the subway had been upgraded by the installation of a hoist - presumably one at each end.

*It is known that during August 1869 a Dr Fawcett made a complaint about a "wet crossing at Cambridge station". We cannot be certain as to what crossing this referred but given the single up / down main platform layout [of the main building] of the time, it may suggest the island platform was still in use and Dr Fawcett was referring to the footbridge. To whatever Dr Fawcett's complaint referred, the island platform had certainly gone by 1875 for, in August of that year, calls were being made for another additional platform.

Both: Grace's Guide to British Industrial History

Photography was very much in its infancy in the mid-nineteenth century but a photograph showing a few yards of the second island platform, viewed from the booking hall, is believed to exist. However, attempts to track it down have, at the time of writing, been unsuccessful. .

During the period of both island platforms, the original booking offices remained in use and access to the latter was - and still is - via the centre three arches of the colonnade. This is one of the very few features of the station which has not changed over the almost two centuries since the station opened; the only difference to speak of is the two booking offices, accessed originally via a common lobby, being merged into one during 1971.

Following the 1863 changes, the island platform and subway, the latter alternatively referred to as the 'luggage tunnel', then became largely forgotten for over a century. Then, in 1981, while British Rail were undertaking some track work, the subway and the foundations of the island platform were rediscovered. The present-day situation with the old Victorian subway is the subject of a number of rumours but the most likely scenario is that it is infilled.

In 1863 the platform was increased in length to 1,250ft and surviving GER records tell us there were numerous other alterations during the period 1863 - 1869. Some of these were in connection with the building of the Great Northern Railway (GNR) station and the Railway Clearing House offices. The bay platforms also appeared from 1863, the same year in which plans showing the island platform last appeared.

Having gone through the island platform phase and the 1863 alterations, the builders set to work again in 1908 with, among other things, a further widening of the platform but the supports were to remain the bugbear of Cambridge station's main platform until the British Railways era.

Over the decades a number of further proposals for an island platform were put forward but in the event it was to be a century and a half before Cambridge station would gain its third such platform, to cater for 12-car trains and the Thameslink scheme. This is today's platforms 7 and 8.

The removal of the platform colonnade left the end elevations of the station building asymmetrical, as the image below shows.

Detail from an image in the John Mann Collection

Compare the end of the main building to that seen on the 1845 engraving which as the station building is concerned gives a quite accurate visualisation. The rectangular moulding on the end wall was originally central and this gives a good idea of just how much the platform side of the building was altered. It is not known if the ornate roof overhang originally extended around the track side of the building; if it did it was not replaced following the 1963 alterations. Note the smaller arch to the left of the colonnade; there was a corresponding arch on the platform side until the 1863 rebuild. The wall on the left was not original and was probably built at the time the north bay appeared.

The coats of arms

This is an opportune moment to mention the Coat of Arms plaques which adorn the station. These date back to the building of the station and others were added as additional buildings were erected over the years. Two later additions can be seen on the building on the left; this was until recently the British Transport Police office. The plaques, which did not appear on the east side of the building, mainly depict the Coat of Arms of Cambridge undergraduate colleges while others depict the Coat of Arms of local noteworthy people and one depicts the Coat of Arms of the City of Cambridge. There are thought to be 29 of these plaques, depending upon your point of view as there are at least two blanks.

It seems that over the years some plaques have disappeared, only to later reappear in different positions, while consideration is given from time to time for additional plaques and indeed British Rail added further examples to the north and south wings in 1986. It is also likely that with the ceaseless construction developments of the 21st century at and around Cambridge station, further relocation of some plaques will occur.

Signalling and the electric telegraph

Hardly anything is known about specific signalling arrangements at Cambridge at the time of the station's opening, but we do know the ECR used a mix of hand and mechanical signalling throughout its system. Where hand signalling was used, arm positions (in the absence of flags) did not correspond to those of mechanical signals; as we will see below, this must have caused confusion at times. Signalling was undertaken by men stationed at intervals of 2 - 2½ miles along the line and it was also the job of these men to ensure the line was free of obstruction; people, animals, debris etc. Before the introduction of the electric telegraph, signalling was operated on the inherently dangerous 'timed interval' system; having given a train permission to proceed, a signalman would then wait a length of time as laid down in the rule book before allowing the following train to proceed. These 'signalmen', who were railway employees, were actually policemen and were also responsible for the day to day operation of (railway) stations as well as the duties normally associated with policing insofar as railway property was concerned. This was the origin of what is now the British Transport Police, although the BTP has long since ceased to have any involvement with the actual running of the railways.

The semaphore signal of the type mounted on a post and using a pivoting arm was invented in 1841 and the ECR made use of a then-common slotted-post type, which gave three indications as opposed to the two of other semaphore types; arm vertical and thus out of view - Clear; arm at 45deg - Caution; arm horizontal - Stop. At night, signals were lit by oil lamps and colours were; white - Clear; green - Caution; red - Stop. Hand signals, in the absence of flags, were; arm outstretched horizontal - Clear; one arm held up vertical - Caution; both arms held up vertical - Stop. Amusingly, the ECR Rules for Stop hand signals included the words 'or waving with violence a hat or any other object'. Where flags were available for hand signalling, a red flag was used for Stop and a green flag for Caution. As far as can be ascertained, no white flags were used. With regard to signal post lamps, these appear to have been mounted on top of the posts and thus independent of signal arms which therefore became redundant during the hours of darkness. Surviving diagrams dating from 1846 suggest ECR signal posts were no more than five or six feet tall, so dealing with the coloured lamps during the hours of darkness would not have been any great nuisance.

It is worth diverting for a moment to look at the Newmarket & Chesterford Railway. One surviving record implies the N&C used a different signal lamp system; white - Proceed; red - Caution; blue - Stop. This system appears to have remained in use subsequent to the ECR taking over the operation of the N&C but it is not known if it was also used on the Six Mile Bottom - Cambridge section, given the problems this would have caused at Cambridge.

While all this may seem strange today, in the mid 19th century Britain's railway network was a scattering of independent - and often physically unconnected - companies operating under no particular standardisation. Standardisation in respect of signal colours eventually appeared as the railway network grew and more companies lines became physically connected to each other. Amber / yellow for caution signals did not appear until the production of glass so-coloured became possible.

As said, the 'timed interval' system was inherently dangerous but until the electric telegraph came into widespread usage there was little alternative. The electric telegraph, incidentally, was effectively the catalyst which gave birth to signal boxes in the traditional form we know them today. The first successful electric telegraph on a British railway was installed between Paddington and West Drayton for the Great Western Railway in 1838. The story of the electric telegraph in itself warrants a separate feature but this would be outside the remit of this website. To learn more, the excellent work of the late Steven Roberts, which makes a specific mention of the ECR, is worth reading and Steven's work has now been archived by the British Library.

Further information on signalling will be given in Part 2 and subsequently, as developments are more relevant to later periods.

The arrival of the Newmarket line

The Newmarket line finally reached Cambridge in 1851, opening to traffic on 9 October following much delay. The history of the Newmarket Railway can be read here so only the pre 1896 route into Cambridge station is to mentioned in this feature.

The pre 1896 route into Cambridge refers to the section from Brookfields, adjacent to the former Norman cement works, to Cambridge station. From Brookfields the line ran to Burnside where it crossed Cherry Hinton Brook on a bridge (which still exists, albeit in much rebuilt form), along what is today Budleigh Close, across what would become Perne Road, along the south side of Marmora Road, across what would become Coleridge Road and then through what today are the back gardens of the houses on the north side of Greville Road.

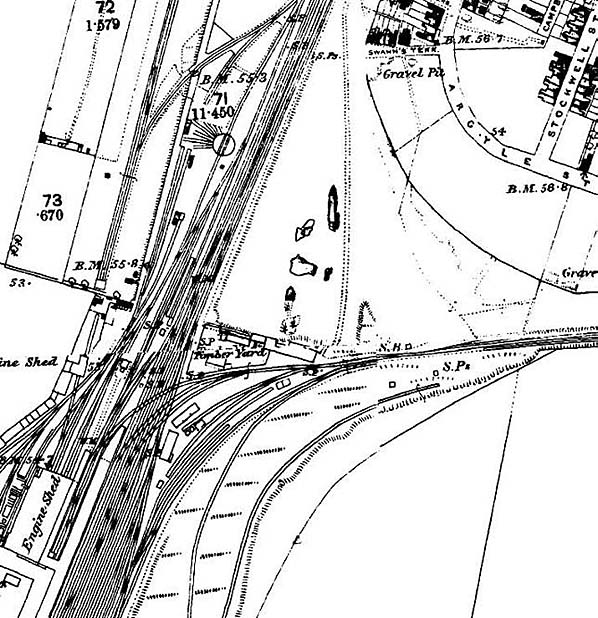

At this point the line was within sight of Cambridge station, which it was approaching at almost a right angle before curving south-west as to approach the station platform. There is thought to have been a triangular junction; the north chord of which swung round to cross Mill Road (then a level crossing). It was this north chord, or provision for it, which gave rise to the characteristic curve of Argyle Street. However, when this chord was actually in existence, if it was, is by no means clear and period maps are too erratic to provide any degree of certainty. One map, from as late as 1927, shows the chord in existence but in use, of course, as a siding. Other maps show sidings on the site of the north chord and connected only at the north end but with too large a radius to have been part of the original triangle. Also, an ECR record from November 1859 states the triangular junction as 'not recommended' but it is not known if this means its construction or its use was not recommended. Photographs of the original Newmarket line in the vicinity of Cambridge station can be seen in Part 2.

Immediately before the start of the [presumed] triangular junction, at its eastern apex, was another connection which enabled trains from Newmarket to bypass Cambridge station and head south. This line ran through what over the years became the large Cambridge goods yard east of the station, past the (1869) Great Northern Railway engine shed to emerge and join the main line at Hills Road. Eventually there were two such through roads; that passing through the goods yard and another, originally a siding serving cattle pens, bypassing the yard.

The south chord of the triangular junction approached the station on a sharp curve and in doing so crossed the main lines and a number of other tracks before arriving at what is now platform 4. The curve was planned for a radius of 20ch (chains; 1 chain = 66 feet) but for reasons which remain unclear its as-built radius was a mere 8ch. It may have resulted out of the original plan for the Newmarket Railway to have its own station at Cambridge and this appears to have been the intention until almost immediately before the line was completed. The plans were apparently altered at the last minute to allow Newmarket trains, the line by then operated by the ECR, to use the ECR's station and this would explain the unusually sharp curve into the station platform. What remains a mystery is where precisely the Newmarket Railway station was planned to be. Land boundaries of the time plus the presence of the original and much easier curve into what was to become the GER up goods yard suggest the station might have been planned for roughly where the GNR goods shed later stood. Wherever it was planned to be, we can only guess at how passengers, had the station been built, were supposed to transfer between stations should they have needed to. Surviving documents are unfortunately virtually silent on the matter.

There was a signal box sited at the eastern apex of the triangle, while the junction at Cambridge station platform was known as Cambridge North Junction; this being controlled from the original, pre-1926, Cambridge North box. When the north end bay platforms at Cambridge were built, another connection enabled trains from Newmarket to run into what today is platform 5. This connection, naturally also on a tight curve, necessitated the tapering in of the platform 5/4 ramp west face for clearance reasons.

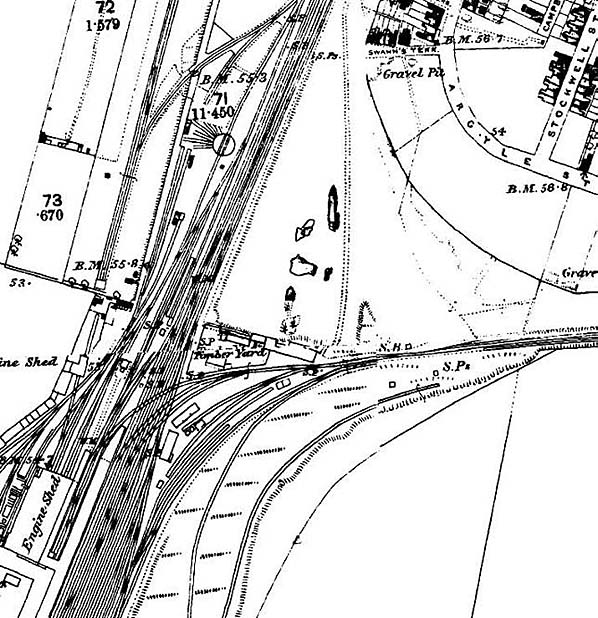

Above is a detail from a map of 1886, a fuller version of which will be shown later. The Newmarket line can clearly be seen entering the station, including the later connection into the bay platform. Also visible is part of the station avoiding line but there is no sign of the north chord of the triangular junction. Note the curve of Argyle Street at top right of the map.

To modern eyes, the junction within the confines of the station platform may appear rather peculiar. We need to remember that when the Newmarket line opened in 1851, the station platforms were much shorter than they were in 1886 and therefore in 1851 the junction was in a more conventional position at the end of the platform.

Further information and photographs of the original Newmarket line post 1896 will appear in Part 2.

Locomotives of the Eastern Counties Railway

Relative to GER and subsequent periods, less is known about ECR locomotives which, of course, would have been seen at Cambridge, so we will give a brief overview to complete the story of the early years.

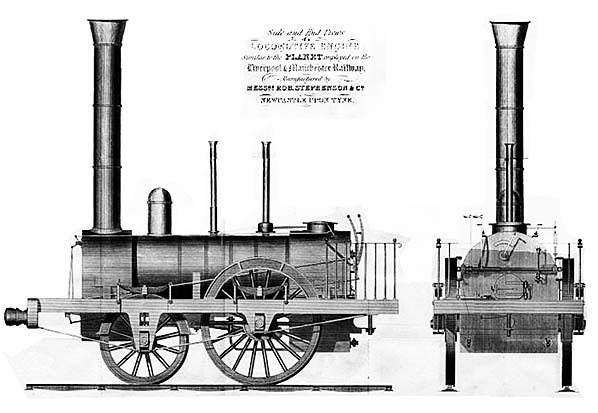

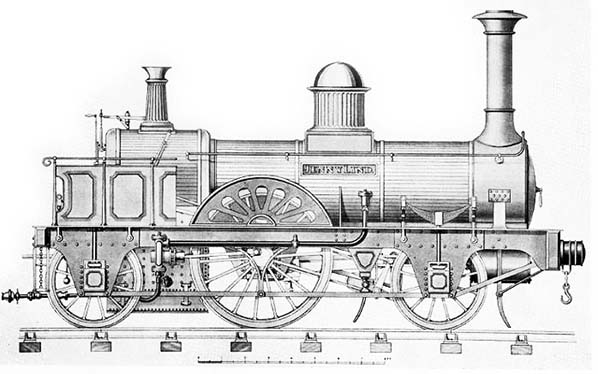

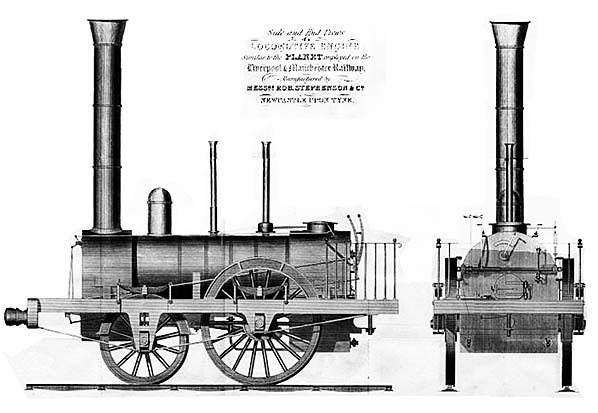

Unsurprisingly given the era, very few photographs of ECR locomotives were taken and even fewer are known to still exist. We therefore have to largely rely upon engravings, with their artistic licence, and works drawings. The ECR used 2-2-0 Planet types; 2-2-2 types similar to that seen in the 1845 engraving; 2-4-0 types; 0-4-2 types; 0-6-0 types. There was also Eagle, the inspection railmotor, and the six Gilkes, Wilson 2-4-0 locomotives inherited from the Newmarket Railway plus a batch of fourteen 2-2-2 types inherited from the N&E. There was also a batch of somewhat odd-looking 4-2-0 locomotives; long boilered and with an enormous single driver (wheels). Two of these were later converted into 4-2-2 form.

One particular oddity, appearing in 1847, was or sort of 'steam carriage' designed by James Samuel, the then ECR engineer, and built by W. Brydges Adams at Bow. It was a four-wheeled contraption with a vertical boiler at one end and seats at the other. The idea had been to create a 'light locomotive' and, according to Cecil J. Allen, Samuel's creation weighed a mere 1¼ tons. Apparently 'The Express', as the contraption came to be known, was very successful and reached a speed of 43mph during a demonstration run from Shoreditch to Cambridge. Over a period of six months 'The Express' ran a total of 5,526 miles with an average coke consumption of a mere 3lb per mile (the early locomotives burned coke, not coal). 'The Express' seems to have been used as an inspection vehicle but was built more as an engineering challenge than anything else. Notwithstanding its limited practical use, its main - and by all accounts only - drawback appears to have been the need for frequent water stops but these were probably no more frequent than for conventional locomotives of the time.

ECR locomotives came from a variety of builders including Robert Stephenson ( 2-2-0 Planet types); Jones & Potts (2-2-2, 2-4-0 and 4-2-2 types); E. B. Wilson (2-2-2 'Jenny Lind' types); Bury, Curtis & Kennedy (2-2-2 types at least); Tayleur & Co. (2-2-2 types); Longridge & Co. (2-2-2 types); Stothert & Slaughter (2-2-2 types).

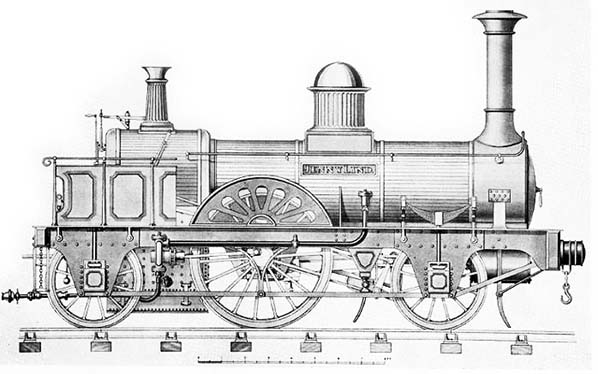

''Jenny Lind' locomotive'. Practical Mechanics Magazine 1848

It should be mentioned that, like Planet, 'Jenny Lind' was actually the name of a particular locomotive and a name which came to be applied to particular locomotive types. However, whereas Planet came to be the name used for the 2-2-0 wheel arrangement in the Whyte Notation, 'Jenny Lind' did not - or at least not officially.

In 1848 E. B. Wilson also supplied the ECR with three 2-2-2 locomotives of the rather ornate Crampton type. These were apparently something of a disaster and were scrapped following a short period relegated to coal trains.

Tayleur & Co. was later to become the Vulcan Foundry, while Stothert & Slaughter was later to become the Avonside Engine Co.

During the period known as the 'Railway Mania' it was not uncommon for a railway company to order locomotives to one specification but then receive something else instead. This appears to have been at the whim of the manufacturers who delivered whatever happened to be convenient for themselves. A somewhat long-running dispute is on record between the ECR and one manufacturer in particular; Messrs Stothert & Slaughter. In this dispute, the ECR was refusing to pay for locomotives until they had been delivered and the 'take it or leave it' approach of the manufacturers seems to have been the reason. There was also a later dispute with Messrs Todd, Kitson & Laird (later Kitson & Co.) which spilled over into GER days but this concerned an alleged poor standard of workmanship.

The 2-2-2 locomotives, in particular, appear to have been very successful machines and were said to have been capable of speeds approaching 70mph in the hands of ECR crews who were, incidentally, known to have a liking for speed. It was these locomotives which initially predominated the Cambridge services. As any train driver knows, achieving speed is one thing but stopping a train is something else entirely and this was especially relevant at a time when there were no continuous brakes. Nevertheless, no accidents of any severity have come to light in respect of the Cambridge line.

The same could not be said of the Planet locomotives.

Above a Robert Stephenson Planet type locomotive is illustrated. It was a drawing for the Liverpool & Manchester Railway but adequately portrays the general design of the Planet type.

Four-wheeled reciprocating steam locomotives are prone to yaw, meaning they try to turn from one side to the other with each stroke of the pistons. The yaw problem is more prevalent with outside cylinder locomotives but is still present with inside cylinder variants. While there is little short term consequence on low speed industrial lines and in shunting operations, in main line use such locomotives damage the track and are prone to derailment. The latter, in particular, was discovered by the ECR to its cost; there were a number a serious derailments, some fatal, involving Planet locomotives travelling at speed. It is said the Planet locomotives could exceed 40mph at the hands of ECR crews and in one instance 50mph was said to have been reached. Recorded accidents all occurred on the Colchester line, perhaps confirming that Planet locomotives were not common on the Cambridge line.

One has to wonder about just how safe the Planet design was. Weight distribution may not have been good, while the short wheelbase would not have been good for relatively high speeds. Also, with a heavy load on the draw bar and only the rear wheels being driven, the front wheels would likely have been quite light on the track.

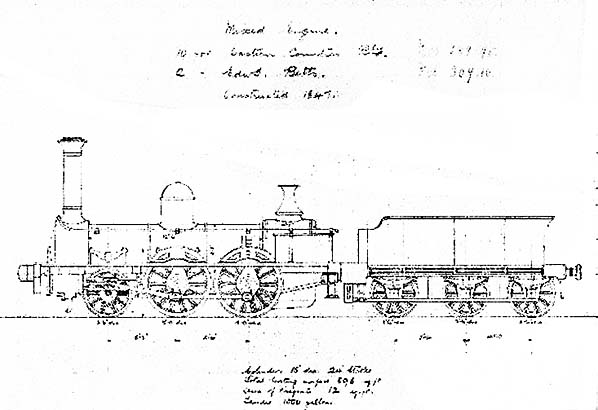

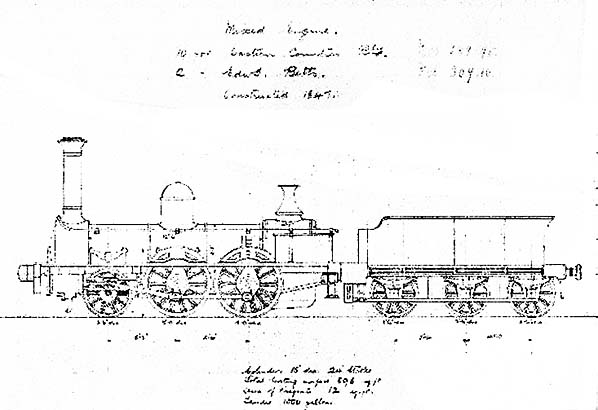

Graeme Pilkington from Vulcan Foundry website

Graeme Pilkington from Vulcan Foundry website

The image above shows a drawing of an actual ECR locomotive built by the Vulcan Foundry in 1847; an outside cylinder, long-boiler 2-4-0 with six-wheel tender. The drawing in fact dates from the early 20th century and was a training project for Vulcan Foundry drawing shop apprentices using information from original documents. A batch of twelve of these locomotives was built; ten for the ECR and two for the contractor Edward Betts. The locomotives were similar to the Gilkes, Wilson machines built for the Newmarket Railway. A cab is still lacking but examination of the drawing shows that by 1847 locomotive design was developing into a form which would still be recognisable a century later. The ex-Newmarket Railway locomotives had been quickly relegated to Peterborough - London coal trains by the ECR and would have been a common sight wheezing through Cambridge during this part of their short career.

Grace's Guide to British Industrial History

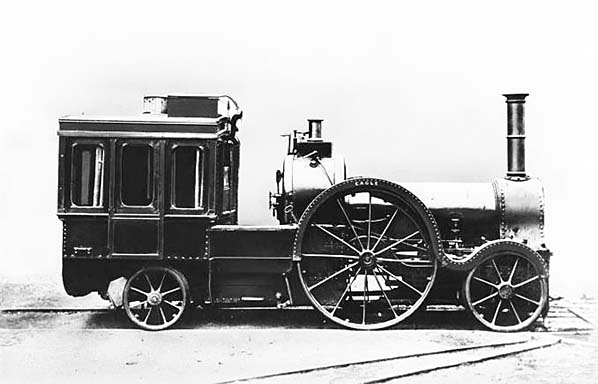

© National Railway Museum / Science and Society Picture Library

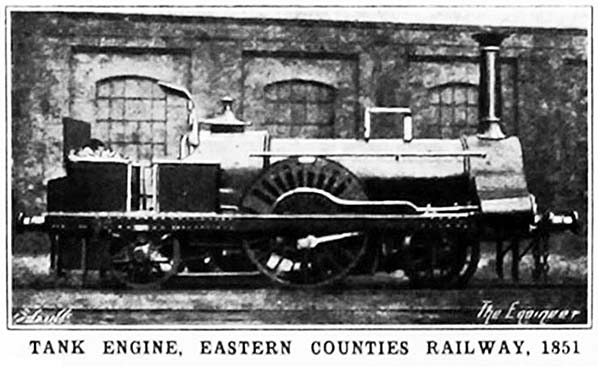

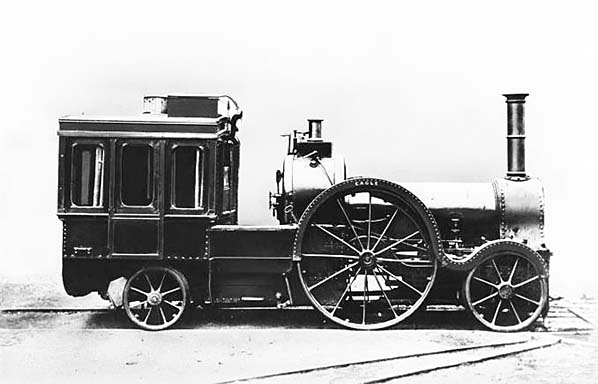

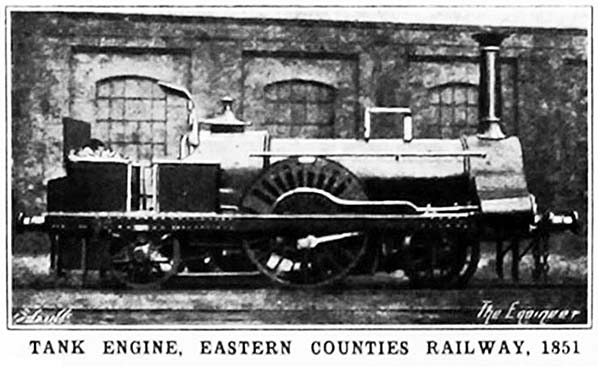

Above are two of the very few known photographs of ECR locomotives or, in the second instance, the inspection locomotive Eagle.

The first photograph shows a 2-2-2T locomotive at an unconfirmed location. The domeless boiler suggests the locomotive is almost certainly of a type designed by John Viret Gooch who had come to the ECR from the London & South Western Railway. The design shows features, such as the ornate splashers and cylinder casings sweeping up to meet the smokebox, which became characteristic of a number of railways during the 19th century due to engineers taking their ideas with them as they moved from one company to another. Note the spectacle plate with its top folded back to offer basic protection for the crew; this was the beginning of proper cabs being provided for locomotive crews. John Viret Gooch was a brother of the better known engineer Daniel Gooch.

Eagle was the only railway locomotive built by Headly Bros. of Cambridge at their Eagle Foundry on Mill Road. The foundry was located at what is today a council depot on the north side of Mill Road bridge and on the down side of the railway. Headly, often misspelled 'Headley', manufactured stationary steam engines and were also responsible for the girders of some railway bridges in the area.

'Eagle' was built in 1849 and was originally open at its rear. The cosy-looking compartment was a later refinement, making Eagle look like something one might have seen in the 1970's TV comedy 'The Munsters'. Compartment lighting is provided, while there are curtains and a speaking tube for communication with the crew.

How the compartment was accessed is not entirely clear; under close examination what appears to be a door is not. The image is a typical official photograph with background removed. Other photographs may have been taken but to date this is the only one known to exist. In 1850, Eagle was involved in an accident near Haddiscoe when it ran over and killed the Norwich District Superintendent. Its subsequent history is not known.

Apart from 'Eagle' and the vertical-boiler inspection contraption 'The Express' mentioned earlier, William Adams, the then ECR locomotive superintendent and better known for his time with the London & South Western Railway, followed up 'The Express' in 1849 with what is accepted as being the very first steam railcar for public passenger use in Britain, if not the world.

We know a fair amount about the railcar. It had a long frame upon one end of which a boiler was mounted, this end then being mounted on a Planet type locomotive underframe. Upon the rest of the frame was mounted a four-compartment carriage body with, it was said, seating for 42 passengers. This end of the railcar was mounted on two rigid axles and thus the entire railcar was rigid. To overcome the inevitable problem of negotiating curves, only the two outermost axles had flanged wheels. The overall length of the railcar is not known but we can estimate it as being in the region of 35ft, so the wheelbase of the flanged axles was probably in the region of 28ft.

The railcar is known to have successfully completed a trial run between Shoreditch and Norwich via Cambridge, the only route to Norwich possible at that time. It is not clear how the railcar was operated when the engine section was at the rear, but as it later operated between Shoreditch and Enfield via Angel Road it appears it was capable of operating in either direction without being turned. If it wasn't, one of the major advantages of a railcar would have been lost.

As a foretaste of things to come, the railcar was withdrawn from service due, it was said, to the problems of having an engine and carriage combined into a single vehicle. The railcar was withdrawn and the locomotive part was rebuilt into a conventional 2-2-2T. Despite the ultimate failure of the railcar experiment, the late Colonel Stephens would almost certainly have approved.

It will be appreciated that, at the time of writing, 170 years have passed since Cambridge station opened and detailed, accurate information from the 1840s is difficult to find without the involvement of considerable time and expense. The above potted history of the early years has been put together mainly from the records of the Eastern Counties and Great Eastern railways which have fortunately survived largely intact. Inconsistencies do, however, exist and this especially concerns the 1845 - 1863 period but we have done our best herein to separate reality from myth and rumour.

For those who are determined enough, a fuller account of Cambridge station and the early train services, London to Cambridge by Train 1845 -1938 by Canon R. B. Fellows and published in 1938 (second edition published 1976) is recommended. This book is now extremely rare but a copy can be seen at The National Archives, Kew. Also, original plans for Cambridge station can be seen in the Parliamentary Archives, Westminster.

Eastern Counties Railway Livery

Railway company liveries can be complex subjects, especially regarding shades, linings and periods in time so as the subject is only semi-relevant to Cambridge we will give brief details, including links to external sites, in certain sections of this feature.

Insofar as ECR livery is concerned, little detailed information has come to light but locomotives are said to have been a light shade of green, described as 'pea green', with brown frames and the same shade of green for buffer beams. Lining was applied but the precise colours are unclear. Smoke boxes and chimneys appear to have been of a further colour, possibly black or even brown carried up from the frames. Passenger rolling stock is thought to have been brown while that of goods rolling stock is not known.

Click here for Part 2: The Pre-Grouping period

or return to Cambridge home page

Trumpington station existed during 1922 to serve the Royal Show and a photograph of it appears in Part 2. Other stations, some still open and some not, are / were located just outside the present city boundary; Shelford, Fulbourne; Histon; Quy; Waterbeach and Harston. Of those, only Shelford and Waterbeach remain open.

Trumpington station existed during 1922 to serve the Royal Show and a photograph of it appears in Part 2. Other stations, some still open and some not, are / were located just outside the present city boundary; Shelford, Fulbourne; Histon; Quy; Waterbeach and Harston. Of those, only Shelford and Waterbeach remain open. 1850 Timetable

1850 Timetable

Graeme Pilkington from

Graeme Pilkington from

Home Page

Home Page