Cambridge - Its Railways and Station[Source:

Darren Kitson]

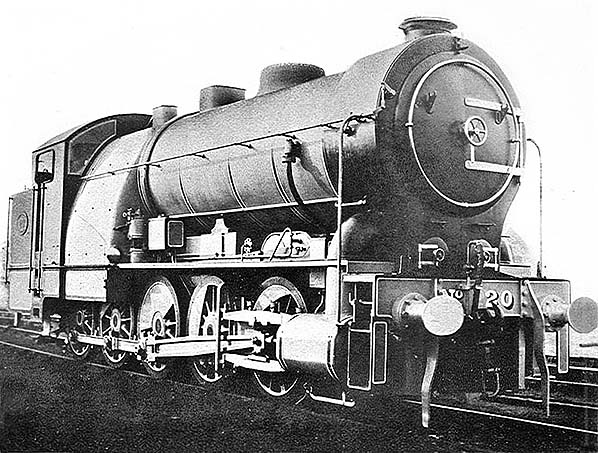

Part 2: The Pre-Grouping Period (continued) GER Class A55 Locomotive No.20

By proving that steam traction could equal the electric traction of the time (Decapod actually beat the criteria set out) all bar one of the electrification schemes failed to get through parliament and the one that did, as late as 1905, failed due to a lack of investors. Therefore by building Decapod the GER had fought off the threat of electric railway competition and its steam-hauled suburban services were safe.

Above is Decapod in her as-built form. She had 4ft 6in wheels, three cylinders, six safety valves (boiler pressure was 200psi), an enormous firebox but little coal and water capacity. Her task was simple; to accelerate a train weighing 300 tons to 30mph in 30 seconds. Trials took place between Stratford and Brentwood from February to June 1903, culminating in Decapod accelerating a train of 335 tons from a standing start to 30mph in a fraction under 30 seconds. The train used in the trials consisted of 18 four-wheeled coaches loaded with pig iron to represent passengers. Having proved herself, Decapod was then redundant and for several reasons it was not considered viable to build more such locomotives, so Decapod was retired until 1906 when it was decided to convert her into an 0-8-0 goods locomotive. In this guise No.20 (the number was retained) became a familiar sight at Cambridge.

Above is the rebuilt No.20; an ungainly contraption which was probably more of an accounting exercise than anything else, meaning it would avoid the losses incurred had the original locomotive simply been scrapped. It appears that very little of the original locomotive was retained in the rebuild; buffer beam, buffers, guard irons, cylinders, slide bars, crossheads and perhaps the wheels look original but little else. Also, the rebuild appears to be steam braked only whereas the original was Westinghouse fitted but this is unsurprising given that the rebuild was intended only for goods traffic The tender was a standard GER high-sided type and the boiler and firebox probably came from the works float. The rebuilt locomotive was said to be no better performing than Holden's 0-6-0 G58 Class locomotives (LNER/BR Class J17). After shuffling up and down the Cambridge line on coal trains for a few years, 20 was scrapped in 1913.

Note the advertisement for the Daily Sketch. This was a tabloid newspaper once popular among the working classes despite its Conservative leanings. The Sketch, as people called it, lost its popularity during the 1960s following a number of controversies and it ceased publication in 1971 and after a life of 62 years. Closure of the Newmarket Line To recap from Part 1, the abandoned section of the original route started at what was later the site of Brookfields signal box and headed west across what are now the lakes formed from the former chalk quarries. It then ran along what today is Budleigh close, then along the south side of Marmora Road and through what are today the back gardens of the houses on the north side of Greville Road. There was a bridge over Cherry Hinton brook, immediately east of Burnside, and east of this was a bridge over the railway for which Jesus College was responsible. The bridge over the brook still exists but in much rebuilt form (it is now concrete and has been for many decades). All traces of the bridge over the railway have long since vanished as the location was quarried post WWII. Apart from Budleigh Close and the curve of Argyle Street, a further clue to the railway's existence is the north side back gardens of Greville Road. As Greville Road stretches west towards Charles Street and Rustat Road the gardens become shorter. This is because the gardens on the south side of Argyle Street were laid out when the railway was still in existence and thus the boundary was dictated by the presence of the railway. When the line was abandoned and Greville Road was built, the gardens of that road could extend only as far north as those of Argyle Street, therefore where the two sets of gardens meet, the demarcation line follows the course of the old railway. At this point the railway began to curve more pronouncedly southwards and it was this curve which dictated the increasing lengths of gardens on Argyle Street and thus the correspondingly shorter lengths of the later gardens of Greville Road. The north chord of the triangle, if it existed, would have branched off just east of today's Charles Street. The 1896 deviation, still in use today albeit now single track, swung north-west at Brookfields and crossed what are today the eastern end of Coldham's Lane and the southern end of Barnwell Road by bridges before turning due west to cross Coldham's Common. There is then the famous sharp curve, with a level crossing on Coldham's Road, before Coldham Lane Junction is reached. The radius of this curve is only a couple of chains larger than the original curve into Cambridge station. The references to 'Coldham' and 'Coldham's' are not typing errors; 'Coldham' is railway spelling for the junction while 'Coldham's' is the now the accepted spelling for the roads and the Common. We know from surviving records that attempts to build the deviation line were ongoing as early as 1873. The problem, it appears, was the railway crossing Coldham's Common. Jesus College was also part of the equation as it was a major landowner on the eastern side of Cambridge. The matter went to parliament and the GER's plans were rejected. The original route into Cambridge thus continued to operate for a further two and a half decades. Further and somewhat long-drawn-out negotiations occurred during the 1890s and this time were successful. At this time Coldham's Lane crossed the railway (the main Cambridge - Ely line) via a level crossing and part of the agreement for the GER's Newmarket deviation line was that they replace the level crossing with a bridge. This is the Coldham's Lane bridge we know today, Bridge No.1547, albeit altered during the intervening years. The original road ran north of the bridge which replaced it; this being the road on which the former Greyhound public house was located. On the other side of the railway, the stub end of the original road for many years provided access to the former and well known scrapyard of Richard Duce. With the opening of the deviation line in 1896 the original route was disconnected at Brookfields. Apparently disconnection occurred immediately, with the original line becoming storage sidings and with buffer stops erected at Brookfields. As we will see from the following image, the line was indeed used for storage although it is doubtful the line ever saw any use post 1896 east of what is now Perne Road. The track was lifted piecemeal fashion during the early 20th century and by c1927 all that remained was the tracks, albeit realigned at their northern end, running through the goods yard and these themselves finally disappeared during the early 1970s when the Cambridge Instrument Co. factory was built on part of the goods yard. The southern end of one of the tracks, however, remained in use into the 1980s to connect the goods yard to the main line at Hills Road. This was the track on which 37114 is seen in an earlier image and when it was lifted c1985 the last tangible evidence of the former Newmarket line disappeared.

The above c1911 image will be of interest to local people. Taken from either a signal post or lamp post it shows the original Newmarket line heading east away from Cambridge station (behind the photographer) towards Brookfields and Cherry Hinton. The points in the foreground are the start of the two tracks which crossed other tracks to reach the station platforms. On the right, where the carriage is stabled, are the tracks which ran through the goods yard to ultimately join the main line at Hills Road. The carriage is No. 327; a six-wheel composite built in 1880 to diagram 200. On the left, just before the start of the double track, a signal box once stood. It was abolished in 1896 and was possibly referred to as Cambridge East Junction but no confirmation has so far been forthcoming. As built, the Newmarket line was single track and it was later doubled. It is thought the original single track is that running straight ahead, while the additional track is that seen branching to the left where the long line of carriages is stabled. The north chord of the triangle, assuming it existed, would have branched off in the distance where the carriages are stabled. Of the tracks branching off into the goods yard, where 327 is stabled, one existed from the outset and the other appeared later, probably c1865. The cattle dock is on its original site, being later moved further south after the cattle market adjacent to Hills Road was built. Evidence suggests the track on which the cattle wagons are stabled was laid to make best use of available space but was never connected to the Newmarket line as the image may suggest. In any case, the cattle siding appears to be at a slightly higher level than the Newmarket line. In the left background the rear of the houses along the south side of Argyle Street can be seen, while the belt of trees in the distance mark the site of what is today Coleridge Road. From left to right across the centre of the image, Charles Street and Rustat Road runs today. The double track in the distance is now the site of the rear gardens of houses on Greville Road; as already mentioned, the curve of the track accounts for the gardens of Greville Road, which is itself straight, becoming shorter as they spread westwards. The open land seen in the image was mainly owned by Jesus College and the scene is totally unrecognisable today with urban sprawl stretching beyond the horizon. Many streets in the area are named after people associated with Jesus College; Rustat, Coleridge, Greville, Davy, Radegund etc

The above view was taken at the same time as the previous image and from the same spot but is looking towards the station. By this time, the station platform had been lengthened to 1,515ft and through where the wagons are stabled on the right once ran a third track which ran into platform 5 of the north bay. We can work out that, by using the carriages in the bay as a form of measurement, the pre-1908 platform would have ended opposite the fifth carriage counting from the right. The carriages in the bay appear to be entirely six-wheelers with at least three being full brakes. On the right, the van behind the open wagon boldly marked 'G E' is Worsdell Telegraph Department van and it appears to have either a ladder or a walkway on its roof. Note that the van body is of the once common outside-framed typed. The decrepit remains of these GER van bodies can still occasionally be seen today in remote corners of farmland, behind hedgerows and so forth. It will be seen in this and the previous image that a lot of track components are laying around. Where they have come from we will never know, although it is reasonable to suggest they may have come from the Newmarket line as it was gradually dismantled back from Brookfields. The building on the left is believed to have originally been stables, in connection with horse shunting. Details of the lone carriage are not known, other than it not being the same one as seen in the previous image. Quite why single carriages would be apparently dumped on the old Newmarket line in this matter is anybody's guess but it is possible they were in some way defective. The track on which the carriage stands ran directly into platform 4, while that to its left connected into one of the platform avoiding roads, later a carriage siding, and then could access platform 1 via connections further south.

Taken at the same time as the previous two images, above we can see the original Newmarket line as it curves eastwards from the station at what was known as Cambridge North Junction. The photographer is standing at what would have been the northernmost extremity of the 1,250ft pre-1908 platform. The image illustrates well the nuisance the Newmarket line would have been with regard to traffic movements. The carriage seen on the curve is presumably the same one as seen in the previous image and we can also see the other end of the stable building in the previous image. The building on the right, adorned with those wonderful period advertisements, is also thought to have been stables. In the left background the houses of Mill Road can be seen while in the centre background the roofs of the part of Argyle Street which runs north to join Mill Road are seen. The section of platform visible dated from 1908 and appears to have been very neatly constructed. 1911 was, incidentally, the year of Britain's first national railway strike. In the above three images not a single soul can be seen, so it is possible the images were taken during the strike. Surviving GER records are quite silent on matters concerning the original Newmarket line's abandonment until a sudden flurry of activity during 1922 when a report was produced by the GER's Land, Rates & Taxes Committee on the state of negotiations regarding a sale or exchange of land involving the GER giving up the old Newmarket line between Charles Street and Brookfields in exchange for nine acres of land owned by Jesus College. The GER had asked for £24,000 towards the cost of new sidings to replace those on the old Newmarket line but the college refused. The GER then apparently washed their hands of the matter. Where precisely the 'nine acres of land' was situated is not clear, but we can safely assume it was land west of Rustat Road and east of the then extent of the railway. In other words, the land which became the extended sidings of the up yard adjacent to Rustat Road and that on which the Cambridge Instrument Co. factory was later built. Much of the up yard had been closed in 1966 although the track remained in situ for some time. The site is now occupied by strange-looking blocks of flats. Despite Jesus College rejecting the GER's request and the latter washing their hands of the matter, things must have been sorted out rapidly for within the following decade the old railway had been abandoned as far west as Charles Street and the GER was busy reorganising its sidings. The two bridges between Cambridge station and Brookfields, that over Cherry Hinton brook and the bridge accessing Jesus College-owned land, are not mentioned in a surviving document listing all GER bridges in 1911. From this, it might be assumed the Brookfields end of the line had been totally abandoned by 1911, yet the Jesus College bridge was mentioned in the 1922 deliberations. From this we can therefore cautiously deduce that the track at the Brookfields end was either intact but disused, or had been lifted, but that the trackbed had not yet been formally abandoned. In the broader spectrum of events, the latter would appear to be the most likely scenario. However, an LNER record from 28 January 1925 mentions amendments to 'Proposed alterations in connection with the removal of the old Newmarket line'. This entry can be interpreted two ways; either the Newmarket line had been removed by 1925 and the proposed alterations were subsequent, or the alterations were proposed pending removal of the line.

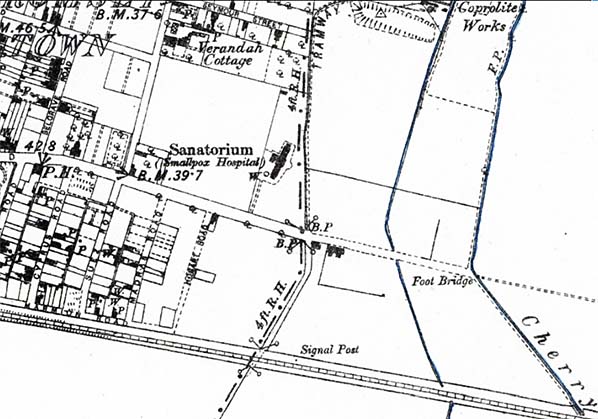

Above is a detail from an 1886 1:10,560 OS map. On the left Marmora Road can be seen running immediately north of the railway. The road running below the sanatorium is Mill Road and the eastern continuation, in broken lines, is Brookfields. Running south-east from the footbridge and alongside Cherry Hinton Brook is what is now Burnside. The signal post stood guard over what is today Budleigh Close. See below. The dog-legged road east of the signal post is now Perne road, although widening has obliterated the dog-leg and the road now continues north as Brooks Road. Note the tramway serving a coprolite works top right.

The above view is worth including even though it is some way east from Cambridge station. It is Budleigh Close, looking east from Perne Road in October 2000. This is the last surviving section of the original Newmarket line and until the 1980s was still the rough trackbed of the old railway. It was then widened, made into a proper road and the pavement added. The railway ran to the left of the image, with the down line being more or less where the pavement now is. The trees in the far distance mark the location of Burnside and Cherry Hinton brook. Beyond that point and to the point where the deviation joins the original line, the trackbed had been obliterated by quarries which are now artificial lakes. The Google Earth 1945 aerial view shows the trackbed intact, before quarrying took over the area while at the bottom of this page can be seen part of the trackbed as it was in 1928. Cambridge station is approximately two-thirds of a mile behind the camera, while the one-time Cherry Hinton station is approximately one mile ahead. On the left approximately where the street lamp now stands, the signal mentioned above once stood. A tramway once ran from here (see map above), heading north along what is now the east side of Brooks Road to serve coprolite workings located in the present-day Barnwell Road area. It would have almost certainly have been narrow gauge and probably horse drawn. Once war broke out in 1914 things became very different. Thousands of young men departed Cambridge by train to join the fighting including from the university. Sadly, many were never to return and the university alone lost 2,500. Just as during the Second World War, the people of Cambridge had to put up with shortages and queues, while the university found itself with problems caused by the large number of students and staff who had gone away to fight. This in turn meant trade suffered; suppliers to the university; landlords; cab drivers etc all felt the consequences. Aerial warfare was then very much in its infancy but there were a handful of airfields around Cambridge; Duxford, Fowlmere and Cottenham. These provided a little relief to the Cambridge region's economy. Duxford, of course, was later to become famous as a Battle of Britain airfield. To give an idea of how busy the railways were, on Christmas Eve 1914 no less than 69 troop trains operated between Bedford and Cambridge. The trains were operated by the Midland Railway, using their locomotives and stock, and carried LNWR pilotmen between Bedford Midland Road station and Cambridge. Records are otherwise a little vague; it is known the troops were on their way to France but it seems they were transferred to other trains at Cambridge as the GER returned the Midland stock to its owners from Cambridge via South Tottenham. The Midland troop trains were numbered B1 to B69 and all other traffic between Bedford and Cambridge was suspended for the day. This operation was something of an exception but nevertheless does illustrate the intensive war-related activities on the railways during both world wars. Nevertheless, Cambridge was one of the few places to still see restaurant cars during the war. For the duration, only the Great Central, Great Eastern, London & South Western and Midland continued to operate restaurant cars. The Great Eastern operated two; the 10am Liverpool Street - Cromer and 5.30pm return, and the 11.50am Liverpool Street - Hunstanton and 4.45pm return. For reasons connected with the war, the Cromer train ran non stop to Marks Tey and then all stations to Cromer, while the Hunstanton service ran non stop to Bishop's Stortford and then all stations to Hunstanton. Passengers could therefore join the train and partake of the restaurant car between, for example, Shelford and Snettisham, Whittlesford and Woolferton or Hilgay and Heacham. During WWI Britain's railways came under state control and the Railway Operating Division of the Army's Royal Engineers requisitioned some 600 locomotives for use in France. This was a hotchpotch collection of various types from numerous different railway companies, including 43 GER Y14 (LNER/BR Class J15) Class locomotives, and needless to say this created problems with maintenance, spare parts and training. It soon became obvious the war was going to drag on for longer than had been anticipated and the Railway Operating Division, better known by the abbreviation ROD, realised it required a fleet of locomotives to a standard design and which could do almost anything asked of it. The ROD opted for the GCR Robinson Class 8K 2-8-0 and over 500 of the ROD versions were built, with the majority being built by the North British Locomotive Co. Known throughout their lives as the 'ROD 2-8-0's', most were sent to Europe but some remained in Britain. Of the 43 Y14s sent to France (and Belgium), some would almost certainly have been Cambridge-based locomotives. All eventually returned home although one, No.513, had been damaged and was withdrawn in 1920. After the armistice of 11 November 1948 (WWI did not officially end until 1919) many RODs returned to Britain but others continued operating in Europe including, after the armistice, in Germany. Others ended up as far away as China and Australia and in the latter country they continued in operation, on a mining railway, until 1973. Three of them are known to still exist at the time of writing. Back in Britain the RODs were initially loaned to various railways and then sold to them. From 1923 the LNER, which had incorporated the GER that year, bought no less than 273 examples and these became Classes O4/2 and O4/3. It is one of the latter we saw at Cambridge shed in an earlier photograph. The RODs became a familiar sight at Cambridge and examples could be seen virtually to the end of steam in the area and BR did not withdraw its final example until 1966. The type is now extinct in Britain; the preserved No.63601 not being one of the examples built for the ROD although it is virtually identical to them.

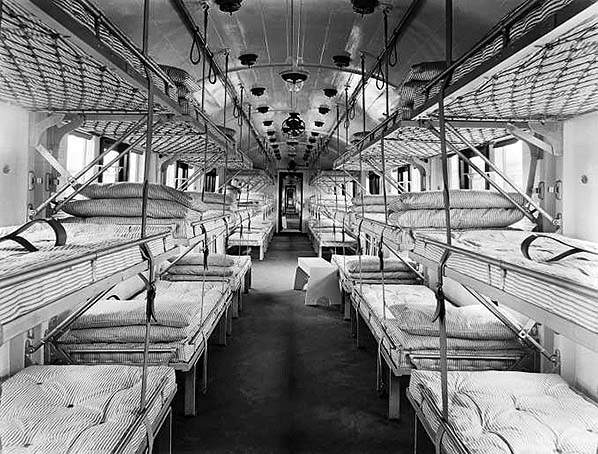

The above pair if images show the interiors of just two carriages of an ambulance train. The first image shows a ward car and the second a pharmacy car. This train was built at Derby and actually saw service in France but was typical of the type which brought the wounded to Cambridge. Such trains carried all the facilities and staff, including for servicemen suffering mental health issues, which would have been found in the hospitals of the day. They were lengthy trains, 16 vehicles being standard, and were very clearly marked externally with each vehicle having large red crosses on white backgrounds - the standard Red Cross symbol. Many thousands of wounded servicemen owed their lives to these trains and those who manned them, with the trains themselves being largely financed by voluntary donations. Over in Europe, the trains were used to take casualties from France and Flanders to Boulogne for the sea crossing to either Southampton or Dover. The Port of Dover received 1,260,506 casualties and 7,781 ambulance train movements transferred the casualties to 196 destinations, one of which was Cambridge. Nurses were, of course, almost exclusively female in those days. While many hundreds of nurses staffed the ambulance trains, many more women stepped into the shoes of men who had gone away to fight and a splendid job they did too. On the railways, women did almost any job which was normally a male preserve other than driving, firing and the heavy engineering tasks and Cambridge was no exception. Following the end of hostilities, government control during WWI had been seen as beneficial to the railways which had consisted of countless small companies often in competition with each other, this being in no small part a legacy of the 'Railway Mania' of the 19th century. The result was the creation of The Railways Act 1921 which saw most of Britain's railways formed into what came to be known as The Big Four (a name, incidentally, coined by the The Railway Magazine); GWR, SR, LMSR and LNER. Also known as The Grouping, the Act came into effect on and from 1 January 1923 and on that date the Great Eastern Railway ceased to exist. Thereafter Cambridge was in London & North Eastern Railway (LNER) territory but also served by the London, Midland & Scottish Railway (LMS), the former having also swallowed up the GNR and the latter the LNWR and Midland Railway.

Trumpington station was open for just five days between 4 - 8 July 1922 and was built to serve The Royal Show. The above view is looking south. Passenger platforms were provided on the up and down relief roads of the London line (left) with the third platform face (right) being for goods traffic Long Road runs across the picture in the background; the bridge over the LNWR Bedford line can be seen in the right background while in the left background can be seen the level crossing over the London Line. Trumpington signal box is also visible adjacent the the level crossing. A bridge replaced the level crossing in 1935; the bridge was built to span four tracks but has only ever spanned two. The platform on the left was stated as being 500ft x 27ft while that in the centre was stated as being 500ft x 45ft. Although not obvious from the image, the up side platform extended further south than the other platform. The goods platform road was a loop, connecting to the down relief road near Trumpington signal box at its south end and behind the camera at its north end. The road to its right, where the open wagon and what appears to be a crane sits, was a dead end siding connected to the goods platform road at its south end. The track ends abruptly just in front of the open wagon. Strangely, perhaps, no platforms were provided for the LNWR line. Passengers detraining from down trains accessed the showground via the platform ramp in the foreground and a temporary level crossing over the LNWR tracks. How passengers detraining from up trains accessed the showground is not clear, but there was a footpath from the south end of the up platform to Long Road and another entrance to the showground just west of the LNWR bridge. When the GER was formed in 1862 its livery, at least as far as locomotives are concerned, appears to have been something of a follow-on from that of the Eastern Counties Railway; essentially pea green and brown although Sinclair is known to have varied the shades. An excellent description has been provided by the Great Eastern Railway Society and which can be read here and in the light of this there is little point in repeating the information. As well as the liveries of the GER, including its famous Prussian Blue (alternatively referred to as Royal Blue, presumably due to the locomotive so painted for HM Queen Victoria's journey to Chingford), Cambridge was also graced with the green of the Great Northern Railway, the so-called Blackberry Black of the London & North Western Railway and the green (pre 1883) and Crimson Lake (post 1883) of the Midland Railway. Details of the GNR livery can be read here, as can that of the LNER, while LNWR livery details can be read here. Click here for Part 3: The Big Four period

|

The origins of Decapod could be said to have lain with the Central London Railway, now part of the Central Line of London Underground. Despite the well known problems of unsprung weight with the Central London's electric locomotives, the scheme was considered a success as had been, to a point, the earlier City & South London Railway which became partly abandoned and partly incorporated into what is now the Northern Line. As a result of the Central London's success a number of schemes were put before parliament for electrified suburban railways in north-east London. The politics of these schemes were complex and as they are not directly relevant to Cambridge we will avoid them here; suffice to say that the schemes were a serious threat to the GER's suburban traffic and that is where Decapod entered the story.

The origins of Decapod could be said to have lain with the Central London Railway, now part of the Central Line of London Underground. Despite the well known problems of unsprung weight with the Central London's electric locomotives, the scheme was considered a success as had been, to a point, the earlier City & South London Railway which became partly abandoned and partly incorporated into what is now the Northern Line. As a result of the Central London's success a number of schemes were put before parliament for electrified suburban railways in north-east London. The politics of these schemes were complex and as they are not directly relevant to Cambridge we will avoid them here; suffice to say that the schemes were a serious threat to the GER's suburban traffic and that is where Decapod entered the story.

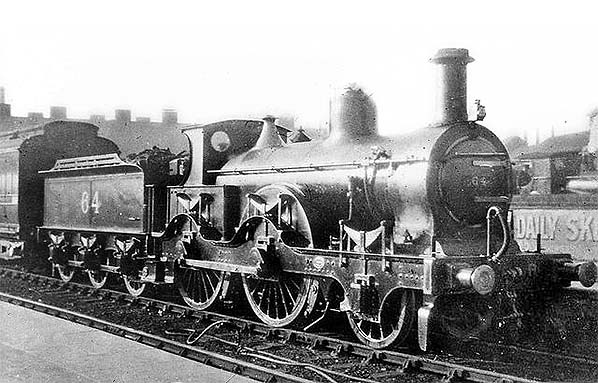

Typical of Midland Railway trains from the Kettering line for many years was Matthew Kirtley 800 Class No.64, seen above at platform 6 sometime between 1909 and 1923. These locomotives dated from 1870 and the last was withdrawn c1936. As mentioned elsewhere, the Kettering line required small, light locomotives because of weight restrictions on the St Ives - Huntingdon - Kimbolton section. These delightful Victorian relics were briefly replaced by other small, lightweight and almost as ancient Deeley and Johnson 2F types until the Ivatt 2MTs took over after the Second World War.

Typical of Midland Railway trains from the Kettering line for many years was Matthew Kirtley 800 Class No.64, seen above at platform 6 sometime between 1909 and 1923. These locomotives dated from 1870 and the last was withdrawn c1936. As mentioned elsewhere, the Kettering line required small, light locomotives because of weight restrictions on the St Ives - Huntingdon - Kimbolton section. These delightful Victorian relics were briefly replaced by other small, lightweight and almost as ancient Deeley and Johnson 2F types until the Ivatt 2MTs took over after the Second World War.

The events of 1922 are quite revealing if we read between the lines. The council wanted to build a new road over part of the old line and Jesus College wanted rid of the bridge, mentioned earlier, for which the college was responsible for maintenance. The benefits to Jesus College of the removal of the bridge had also been mentioned in the 1873 deviation plans which, as we have seen, came to nothing. The planned new road came to nothing either and it was not until the 1980s that what is now Budleigh Close was made into a proper roadway. Some sources say Natal Road was built on the trackbed but this road is north of the old line. Marmora Road existed before the line was dismantled and sits immediately north of the former trackbed. So, what is revealing? The fact the GER requested £24,000 from Jesus College suggests it was the college which was pushing for the old railway to be abandoned and less so the GER which by then was only using the old railway as a siding.

The events of 1922 are quite revealing if we read between the lines. The council wanted to build a new road over part of the old line and Jesus College wanted rid of the bridge, mentioned earlier, for which the college was responsible for maintenance. The benefits to Jesus College of the removal of the bridge had also been mentioned in the 1873 deviation plans which, as we have seen, came to nothing. The planned new road came to nothing either and it was not until the 1980s that what is now Budleigh Close was made into a proper roadway. Some sources say Natal Road was built on the trackbed but this road is north of the old line. Marmora Road existed before the line was dismantled and sits immediately north of the former trackbed. So, what is revealing? The fact the GER requested £24,000 from Jesus College suggests it was the college which was pushing for the old railway to be abandoned and less so the GER which by then was only using the old railway as a siding.

Home Page

Home Page