As with everywhere else, during the Second World War (WWII) Cambridge was a very different place to what it was during the First World War for two mains reasons; a) the advancements in aerial warfare and b) certain racial and eugenics policies of the Nazi regime in Germany. Both were to make their mark on Cambridge, the latter in the form of the Kindertransport.

The Kindertransport

During 1919 in Munich, Germany, one Anton Drexler had formed the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (English: German Workers' Party), abbreviated to DAP. Among the followers of the DAP was a young army corporal who had been decorated for his courage during WW1. On 24 February 1920 the DAP was renamed Deutsche Nationalsozialistische Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers' Party) or NSDAP, better known as the Nazi Party. In 1921 the young corporal became leader of the NSDAP; he was something of a drifter and one who did not make friends very easily but became known for his political beliefs and his effective, albeit monologue, public speaking. His name was Adolf Hitler.

Long before the death camps at Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek and Auschwitz-Birkenau began operations, the Nazis began to single out the physically and mentally handicapped, the so-called feebleminded (a general term which embraced those who were judged lazy, petty criminals, slow learners and so on) and others who were considered 'useless eaters' and a 'burden on the state'. Initially it was just children, then it progressed to adults and these people were ordinary Germans - not Jews or any other people the Nazis decided were supposedly 'inferior'. These people were murdered under the Nazis 'euthanasia programme', better known as Aktion T4*, at killing centres set up at Hartheim, Hadamar, Sonnenstein, Grafeneck, Bernburg and Brandenburg. The killing was later extended to include concentration camp prisoners and, under the code 14f13, at ordinary hospitals after the original killing centres had ostensibly been shut down in 1941 after the killings had become public knowledge. During that year the first of the death camps, Chelmno, had begun operating using gas vans. This camp, situated at the Polish village of Chelmno nad Nerem, predated the decision the instigate mass extermination of the Jews.

*From the address of the organisation, Tiergartenstrasse 4, Berlin. This was a Jewish owned villa confiscated by the Nazis; it no longer exists but a memorial and information board now marks the site. The memorial is a representation of one of the infamous grey buses of Gemeinnützige Krankentransport GmbH, known in short as Gekrat; a front organisation used to transport victims to the T4 killing centres.

Meanwhile, Dr Goebbels propaganda machine had been busy whipping up virulent anti-semitism; blaming the Jews for Germany losing WWI and for just about every other supposed problem facing Germany. It was with hindsight a foregone conclusion that Aktion T4 would in time develop into 'The Holocaust' but this could not happen during peacetime for a number of reasons nor, it seems, was it planned in the years prior to the war. In the interim the Nazis operated a policy of exclusion for the Jews. The measures were draconian to put it mildly; the details are lengthy but suffice to say the idea was to force Jews to leave The Reich. The price of a 'ticket' out for the Jews was the forfeiting of their property, businesses and money. These people fled Germany with literally the clothes they stood in and the meagre amount of possessions the programme, under Adolf Eichmann, allowed them to take. Many Jews, however, chose to remain behind believing the situation would soon blow over - a belief which would later cost them their lives.

The seriousness of the matter facing the Jews became abundantly clear following Kristallnacht of November 1938, and a programme to save Jewish children was put into action. Britain, after much deliberation and a refusal to allow a mass of refugees enter Palestine, agreed to take 10,000 children (the total evacuated was some 20,000) although the final total of arrivals in Britain is thought to have been somewhat less. In Britain, and without meaning to play down the efforts of others involved, the operation was overseen by Nicholas Winton (later Sir Nicholas Winton MBE). The Jewish children were evacuated by train and arrived, via Harwich, at Liverpool Street station where a memorial statue to what came to be known as the Kindertransport can be seen. The Germans co-operated but with the proviso that no Germany ports be obstructed; for this reason the children travelled via Hook of Holland, to Harwich. Nevertheless, some refugees left Germany via Hamburg and Bremen on ships bound for the USA which called, if necessary, at Southampton to disembark some refugees earmarked for Britain.

The Kindertransport continued, evacuating children from Germany, Czechoslovakia, Austria and Poland until the day war was declared. On that day in September 1939 occurred what could be ranked among the most tragic of events concerning these children. A train carrying some 200 children was due to leave Prague but because of the declaration of war and the resulting closed borders the train was never to make its journey. The children onboard who were so very close to being saved did not survive the war and they all eventually perished, probably in Chelmno during 1941. Reports vary as to precisely what happened to this train and its refugee passengers, but the brief account given here is the generally accepted version.

Of the children who did make it to England, some 2,000 came to, or via, Cambridge, whereas others went initially to hostels hastily set up at seaside holiday camps at Dovercourt and Pakefield (Harwich and Lowestoft respectively). In March 1939, the first batch of children, around 100, arrived at Cambridge station, being overseen by the Cambridge Refugee Children's Committee (CRCC). Those who went to the holiday camps arrived earlier, in December 1938. Holiday camps are summer seasonal establishments and in those days did not have heating, so conditions in the bitter winter of 1938/9 were quite appalling for the bewildered and frightened children in the camps which faced the winter wrath of the North Sea. The CRCC dealt with refugee children, while the Cambridge Refugee Committee (CRC) dealt with adults and families and was connected only indirectly with the Kindertransports.

The children, who ranged from infants to 17 year olds, separated from their families, had arrived in a foreign country which had a language and culture alien to them. Some Jews had already fled to Britain but the influx of large numbers of refugee children did provoke some hostility and resistance from at least one rabbi who was opposed to children of the Jewish faith being looked after by Christian British families. Whilst this could be said to be understandable, under the circumstances which brought the children to Britain it was in reality quite disgusting. There were also problems in the countries from which the refugee children came. As far as the Germans were concerned, at that point in time, a Jew was a Jew and they just wanted rid but others did not see it that way. There were arguments from the Jews themselves, in particular the rabbis, over which children should be saved and based upon religious considerations. For example, so-called non-Aryan Christians, that is, baptised Jews, were subjected to attempts to exclude them from the evacuations. Nicholas Winton won the argument with his words, paraphrased here, "What would you rather have? a baptised Jew or a dead one"? The use of the words dead one are significant as they indicate just how perilous the situation for the Jews was and this was, remember, long before the Nazis decided on mass extermination - The 'Final Solution' to the Jewish question as hatched at the Wannsee Conference of January 1942.

Furthermore, in many countries Jews were mistrusted and at best merely tolerated by the majority of populations and Britain was no exception. This had been the case for centuries. For example, Britain expelled her Jews in the 13th century and it wasn't until the 19th century that Jews, in spite of Benjamin Disraeli, were permitted to sit in parliament. In the 1930s Britain, as elsewhere, was suffering from The 'Great Depression' and as we have already seen Cambridge had its share of poverty and unemployment. Given the anti-semitism which existed and the poverty and unemployment caused by the depression, there was some unrest in Britain over the taking in of refugees. As war clouds gathered there was further unrest because the Jewish refugees were, after all, largely Germans. Once war was declared these [adult] refugees became, by default, enemy aliens and so, for fear of spies, on Churchill's order, they were sent to an internment camp. This internment involved enemy aliens over 16 years old and as the Kindertransport children were up to 17 years old, some of them were also involved. A total of 281 refugees from Cambridge were interned on the Isle of Man.

Furthermore, in many countries Jews were mistrusted and at best merely tolerated by the majority of populations and Britain was no exception. This had been the case for centuries. For example, Britain expelled her Jews in the 13th century and it wasn't until the 19th century that Jews, in spite of Benjamin Disraeli, were permitted to sit in parliament. In the 1930s Britain, as elsewhere, was suffering from The 'Great Depression' and as we have already seen Cambridge had its share of poverty and unemployment. Given the anti-semitism which existed and the poverty and unemployment caused by the depression, there was some unrest in Britain over the taking in of refugees. As war clouds gathered there was further unrest because the Jewish refugees were, after all, largely Germans. Once war was declared these [adult] refugees became, by default, enemy aliens and so, for fear of spies, on Churchill's order, they were sent to an internment camp. This internment involved enemy aliens over 16 years old and as the Kindertransport children were up to 17 years old, some of them were also involved. A total of 281 refugees from Cambridge were interned on the Isle of Man.

The Cambridge Daily News, was a typical local 'rag' of the time which placed more importance on coverage of, say, how well some local vicar did at his church fete rather than on coverage of more important events. This was well illustrated by the newspaper's rather lame coverage of the LMS diesel unit in which they seem to have struggled to find something to say but given what we have outlined above, the newspaper's silence on the Jewish plight could be said to have been expected. However and, it must be said, to its credit, the Cambridge Daily News did a massive U-turn following Kristallnacht. For an entire week, the newspaper, as indeed did others across the country, made what was happening in Germany its headline news and did so in some detail. As it was before war was declared, news reporting still enjoyed a degree of freedom - even from within Nazi Germany and despite attempts made by the Nazis to cover certain things up - and appears to have been the catalyst by which the refugee children were, by and large, welcomed to Cambridge. In some cases the children were met by their foster families directly off the trains at Cambridge station and in all cases by members of the Cambridge Refugee Children's Committee. Later, a social club for the refugees was set up in Cambridge where they could mix, have meals, converse in their own language and so on. Generally very successful, the club was located at 55 Hills Road; close to Station Road corner, the premises is now, at the time of writing, a barber's shop. This address was also the Committee headquarters and jurisdiction covered not just Cambridge but much of East Anglia including Norwich and, further west, Bedford. The keystone of all these efforts was the late Greta Birkill; a determined and fearless woman which we will probably never see the likes of again.

The children's stay in Britain was intended to be only temporary but nevertheless some and / or their descendants remain in the Cambridge area to this day and we should remember that the majority of these children (some 80% it is thought) were never to see their parents or older siblings again for they had also taken a train journey - on the so-called 'resettlement trains' to the death camps in occupied Poland or to concentration camps where they were starved, worked or beaten to death. The vast majority, however, who had not fled and who were still alive in 1942 ultimately perished in the death camps of which the most notorious were Birkenau (Auschwitz II) and Treblinka at which were murdered an estimated 1.3 million and 0.8 million respectively. The precise figures will never be known. The total number of Jews murdered by the Nazi regime and its collaborators by various means is thought to be at least 6 million. The six death camps, all of which were located in occupied Poland, accounted for approximately half that total.

Obviously we cannot mention the story of the Cambridge refugees without giving some background information, so the very brief account above, which hardly scratches the surface, has been given. The handicapped and the Jews were not the only groups to suffer Nazi persecution and the brevity of this account is in no way intended to offend any of those other groups. It is simply beyond the remit of this Cambridge feature to go into further depth.

It is convenient to mention here that following the declaration of war, Cambridge also became a destination for London evacuees. Most of these arrived at Cambridge station from Liverpool Street, with lesser numbers arriving from King's Cross. This was in the period known as the 'Phoney War' which we have already mentioned and many evacuees soon made the short journey back to London, only to return once the Blitz began. As we will later see, at least one London evacuee was thought to be among Britain's first civilian causalities of WWII when Cambridge was bombed in the summer of 1940.

Above are two views of the kindertransport memorial at Liverpool Street station. the first is by Colin Pyle and the second by Wjh31. both are reproduced under creative commons licence. Among those present at its unveiling in 2003 were the then Home Secretary David Blunkett, Sir Nicholas Winton and Bertha Leverton; one of the rescued children who came to Britain with her brother. Similar memorials have been erected at a number of other locations in Europe.

Wartime Cambridge and the Railway

Like the rest of Britain, Cambridge was subject to rationing, the blackout, a military presence, men away fighting or doing their day jobs as well as being active in the LDV (Local Defence Volunteers) or Home Guard as it was soon renamed on Churchill's instigation, while women did their bit on the Home Front. The Pye factories were involved in war work and Cambridge Airport (Marshall's) was very busy with aircraft production. The airport had moved to its present location in 1938, having previously been located nearby on what today is the Whitehill estate.

On the Home Front Cambridge, as elsewhere, turned over public land to the growing of food as part of the 'Dig For Victory' campaign while air-raid shelters popped up everywhere and sandbags became a common sight. Cambridge was literally surrounded by dozens of military airfields, fuel and ammunition dumps and all the other trappings of war. All these sites needed supplies, both of military equipment and for their personnel. The railways were vital for these needs as well as the needs of the military in general and, as in the First World War, Cambridge received many ambulance trains which brought the wounded to hospital facilities in the area. These trains often ran to Barnwell Junction in order to keep the main line and main station at Cambridge clear but quite how these lengthy trains were handled at the small Barnwell Junction station is not clear.

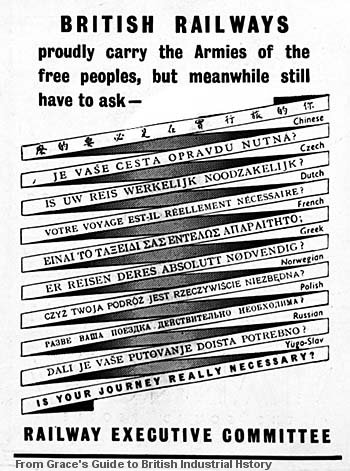

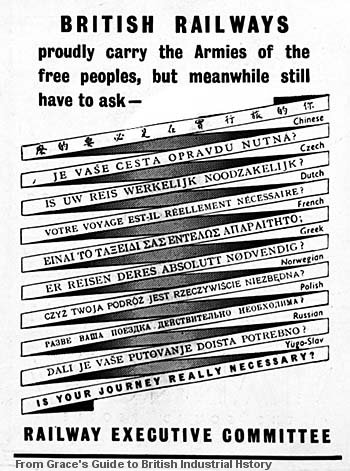

The railways through Cambridge were the backbone of the war effort and transported goods and equipment from the industrial north and midlands to London and the rest of the South-east. Passenger train services were cut back, often severely, in order to give priority to war-related traffic and passengers were asked by posters Is Your Journey Really Necessary? Whitemoor Yard, March, was the focal point for goods traffic converging from the north and midlands to be remarshalled for further distribution southwards. Because of this, Cambridge saw an endless procession of trains from Whitemoor carrying coal, military equipment and other goods to London and beyond - often via Temple Mills. These trains ran, as in peacetime, either via Ely of St Ives; the latter being known to railwaymen as 'The Loop'. Whitemoor and the railway south through Cambridge was thus a target for the Luftwaffe.

The Is Your Journey Really Necessary? notice is seen to the right. This, like others, appeared in many different forms with the most well known being the colourful and slightly humourous versions in poster form. Those relevant to the railways appeared on stations, in publications and sometimes in trains. The idea was two-fold; to convey a serious message and to help keep up morale. This notice was very clever in its design; the English text was at the bottom and as people would naturally read from the top downwards they would be reminded of Britain's non-English speaking allies. The inclusion of Russia indicates the poster was produced after Germany had attacked that country in Operation Barbarossa, June 1941. As we will later see, 'British Railways' was nothing to do with the not then nationalised British Railways. As in WWI, in WWII the railways came under government control and the title was simply a way of referring to all the railway companies collectively. It also had morale-boosting value as it gave a sense of unity.

The Is Your Journey Really Necessary? notice is seen to the right. This, like others, appeared in many different forms with the most well known being the colourful and slightly humourous versions in poster form. Those relevant to the railways appeared on stations, in publications and sometimes in trains. The idea was two-fold; to convey a serious message and to help keep up morale. This notice was very clever in its design; the English text was at the bottom and as people would naturally read from the top downwards they would be reminded of Britain's non-English speaking allies. The inclusion of Russia indicates the poster was produced after Germany had attacked that country in Operation Barbarossa, June 1941. As we will later see, 'British Railways' was nothing to do with the not then nationalised British Railways. As in WWI, in WWII the railways came under government control and the title was simply a way of referring to all the railway companies collectively. It also had morale-boosting value as it gave a sense of unity.

Of the countless aerodromes and other military installations in the region, several were decoys. These were dummy installations made to look, from the air, like the real thing in the hope enemy aircraft would drop their bombs on them rather than on the real targets. By and large, the ruse worked. Whitemoor Yard also had a decoy, as did several important railway yards across the country. The decoy for Whitemoor was located four miles away near the village of Coldham. Lights were set up in a field in the same pattern as those at the yard and left on during the blackouts to confuse bombers, whilst those at the real yard were switched off. It is still there today although, of course, long since put to other uses. Visible from the air, its outline is very similar to that of the real Whitemoor Yard as it was at the time.

The railways of Cambridge, being of strategic importance were, needless to say, targeted by the Luftwaffe. At the time, accurate bombing of specific targets from the air was a matter of luck more than anything else and many of Goering's bombs aimed at Cambridge missed their targets. On the night of 18/19 June 1940, high explosive (HE) bombs were dropped on Vicarage Terrace, a residential area north of Cambridge station and to the west of the railway. Eleven people died including some children, of which at least one is believed to have been a London evacuee. These eleven people are usually acknowledged as having been the first British civilian casualties of the Second World War, this being before the Blitz and at the end of the period referred to as the Phoney War.

During August 1940 more HE bombs fell on Cambridge in two separate incidents; Fenners cricket ground, Leys Avenue, Pemberton Terrace and Shaftesbury Avenue were all hit. Another raid was well off target, with bombs falling harmlessly into fields on the edge of Cambridge. Barrow Road was hit in a single attack during October of the same year.

During 1941 Cambridge received a number of attacks from both HE and incendiary bombs. In the late evening of 16 January an estimated 200 incendiaries were dropped on the Hills Road / Regent Street area; with Perse School being seriously damaged by fire.

Late in the afternoon of 30 January the area around Mill Road bridge was attacked; two railway cottages being hit. Two people died and eleven were injured. There was a heavy raid of 24 February which saw the area between the catholic church (known locally as Hyde Park Corner) and Station Road showered with both HE and incendiary bombs. On 9 May a heavy incendiary raid took place over the area between Hills Road and Trumpington Road, just west of the railway. Fifty houses received direct hits but only five caught fire and of those four were extinguished before any major damage was caused. On 29 August there was another attack on the Mill Road bridge area; this time HE bombs, ten it is thought, fell on Great Eastern Street resulting in two deaths and seven injuries.

Nothing then happened until 28 July 1942 when central Cambridge was attacked. A total of 137 buildings were damaged or destroyed, with three deaths and seven injuries. Later in the war Cambridgeshire received hits from twenty V1 flying bombs (Doodlebugs) but none are known to have come down on Cambridge itself. On 10 November 1944, late in the afternoon, a V2 rocket came down near Fulbourn. The crash site was actually near Fleam Dyke Pumping Station and close to the then extant former Newmarket Railway station at Balsham Road. The bridge over the railway just west of Dullingham station was also destroyed by bombing.

Incendiary bombs were nasty little things. Most people were sheltering and, after a raid, incendiaries could be difficult to locate. They had a delayed action and started fires some time after being dropped but if located in time could be rendered harmless simply by immersing them in a bucket of water, a pond or whatever. Later in the war the Germans dropped exploding incendiaries about which little could be done. It is thought this was the type of device dropped during the raid on central Cambridge. Some of the later attacks on Cambridge are often attributed to the Baedeker raids but whilst other towns such as Bury St. Edmunds and Norwich were Baedeker targets it remains unclear if Cambridge was a specific target. These raids used the 1937 edition of the Baedeker Guide; a German publication aimed at tourism. In it, locations in Britain were graded according the their tourism value by a system of stars. Anywhere given three stars was made an air-raid target. The purpose of the Baedeker raids was mainly to damage morale but, as in many other instances, the Germans failed to understand the 'stiff upper lip' culture of the British people so the Baedeker Raids were ultimately little more than a waste of German resources.

Cambridge was lucky, with only some 20 civilian deaths and some 1,500 injuries. The railway, despite its strategic importance, escaped with only minor damage. In comparison Newmarket, a small town of no great strategic importance, suffered 30 civilian deaths while the Blitz as a whole, which lasted from September 1940 to May 1941, caused some 40,000 civilian casualties with half of those being in London. The people of Cambridge who lived through the war often told of seeing the eerie orange glow in the sky to the south as London burned during the Blitz.

Meanwhile on the railway, there were incidents of trains being attacked by enemy aircraft including one on the Mildenhall branch, near Worlington, and another on the Saffron Walden branch. On both occasions the trains escaped but there were some injuries from, at least, the Mildenhall branch incident.

As in WWI, there was a number of armoured trains patrolling the countryside. In WWII these made use of LNER F4 tank locomotives sandwiched between converted open wagons. The locomotives received only basic protection but the wagons were more heavily armoured to the point where they more resembling of locomotive tenders. Initially manned by Polish soldiers, they were later manned by the Home Guard before they were stood down during 1944.

The armoured trains were identified by a letter and operated in many areas of the country, taking the F4's well aware from their usual haunts. Initially four such trains patrolled East Anglia but by the end of 1940 they had been transferred elsewhere, mainly to Scotland. One of the trains patrolled a triangular route; Cambridge - Hitchin - Bedford - Cambridge. This involved reversals, as did many other routes the trains patrolled, and this was the reason for the use of tank locomotives sandwiched mid-train. The final such train in East Anglia was Train C which patrolled, among other routes, Ipswich - Lowestoft, the Aldeburgh Branch, the Framlingham Branch, the Waveney Valley line via Bungay and Ipswich - Bury St. Edmunds - Newmarket. For reasons unknown, Train C is thought to have occasionally continued beyond Newmarket to Cambridge.

© Imperial War Museum (H 7034)

Due to image scarcity we have used the above image of armoured train K in Scotland. The locomotive is F4 No.7573 and appears to still retain its smokebox destination board brackets. Fuller details of this train and its weapons can be read here. The locomotive later became BR 67153, although this number may not have actually been carried, and was withdrawn from March depot in July 1951. The photograph is posed and as was the practice in wartime for security reasons the location was not stated. A little research, however, reveals the location is almost certainly Aberlady, on the now long-since-closed Gullane branch in East Lothian. This branch left the East Coast Main line east of Longniddry and was intended to reach North Berwick but in the event never progressed beyond Gullane. It closed to passengers in 1932 (another LNER economy measure) and to goods in 1964. The train is standing on the running line and the tracks just visible on the right serve the goods yard. Today, the site of Aberlady station is a caravan park but the platform survives as do some former North British Railway buildings and the road overbridge immediately east of the station.

Meanwhile back at Cambridge, the LNER and LMS were making a number of alterations, mainly in connection with the heavy wartime traffic. On the LNER there were alterations to Coldham Lane Junction and the sidings to the south, the up goods yard was extended, the hump yard relocated, water supplies for locomotives improved (the pump house at Chesterton Junction was part of this scheme), alterations made to private sidings and in particular those serving Messrs Travis & Arnold and Messrs Ridgeon, improvements to and relaying of junctions to the through goods lines. On the LMS, Cambridge Goods Yard box was rebuilt during 1943. The new box was given a brick base and extra equipment in connection with expansion of sidings at Trumpington (Long Road). Staff facilities were provided at the sidings and Trumpington Ground Frame was improved by provision of some shelter from the weather. All this work was undertaken with no disruption to passenger or goods trains.

It is easy to assume the endless procession of goods trains Cambridge handled during the war all carried shells, bombs and other weapon-related items but this was not so. Trains still carried the same goods for domestic use as during prewar days; military vehicles; troops; raw materials for war production; fuel and other oils; rubble from bombed areas.......the list goes on. In the planning for 'Operation Overload' (D-Day), traffic increased significantly. Some trains ran in connection with the construction of P.L.U.T.O., the undersea pipeline supplying fuel to the Allies, while others carried tanks en route to Hampshire and onwards to France. Some of these tanks were loaded onto trains at Newmarket's old station for onward movement via Cambridge.

On the locomotive scene, the former ROD 2-8-0s were continuing to do their duty while the Riddles* War Department 2-8-0 and 2-10-0 types appeared as did the USA S160s and the ubiquitous Austerity 0-6-0 saddletanks which were a Riddles idea based on an existing Hunslet design. The most common of these types at Cambridge was the Riddles 2-8-0; usually referred to as the WD 2-8-0 or, at least to enthusiasts, the 'Dubdees'. They carried War Department numbers and it was one of these, No.7337, which was involved in the Soham ammunition train explosion of 2 June 1944. 7337 went on to become Army No. 400 'Sir Guy Williams' on the Longmoor Military Railway. She ran until 1965 when she suffered a boiler failure and was scrapped c1967 but lives on in model form, being produced in 4mm scale by Bachmann. It is said that the explosion at Soham was heard in Cambridge, some 14 miles to the south-west, while the remains of the wagon which exploded remain at the bottom of in infilled crater to this day as passengers pass obliviously over the site in modern diesel multiple units.

*Robert Riddles, a man with a long railway career to his name, rose to become Locomotive Assistant to Sir William Stanier of the LMS and when WWII broke out moved to the Ministry of Supply. It was in the latter capacity that he designed the WD 2-8-0 and 2-10-0 locomotives. In 1948, Riddles in effect became Chief Mechanical Engineer of the British Railways Board and went on to be responsible for the BR Standard steam locomotives. He died in 1983, aged 91.

The military presence at Cambridge was further enhanced by the US Army General Depot G-23 at Histon. Despite the name, this depot was actually located between King's Hedges Road and Milton Road. A rail connection to the St Ives line was located just west of King's Hedges Road level crossing. Three Austerity 0-6-0ST locomotives worked here and could frequently be seen at Cambridge shed where they presumably went for maintenance and repair. The locomotives appear to have been changed at intervals but one that is known to have worked at the depot was the now preserved WD192 'Waggoner'.

Depot G-23 was later used by British Forces and it closed in 1959. Today, the site is bisected by the A14 road and Cambridge Science Park is built on the south part of the site. Until very recently, large concrete stop blocks could still be seen in what was by then fields north of the former St Ives railway line.

This link, from the D-day Museum, Portsmouth, website, gives a list of US bases across Britain. For those in Cambridge and the surrounding area it is quicker to search the document using keywords Cambridgeshire or Histon for specific details of G-23. Readers may be surprised to learn just how many military establishments there were in the Cambridge area during WWII and should remember the list gives only US establishments and not the countless British military establishments also in the area. All of these establishments relied in one way or another on the railways and thus gives an indication of just how busy Cambridge and its railways were during wartime.

This link, from the D-day Museum, Portsmouth, website, gives a list of US bases across Britain. For those in Cambridge and the surrounding area it is quicker to search the document using keywords Cambridgeshire or Histon for specific details of G-23. Readers may be surprised to learn just how many military establishments there were in the Cambridge area during WWII and should remember the list gives only US establishments and not the countless British military establishments also in the area. All of these establishments relied in one way or another on the railways and thus gives an indication of just how busy Cambridge and its railways were during wartime.

Then and now aerial views of Depot G-23 can be seen on Google Earth by switching between present day and 1945 views. Use Cambridge Science Park as the search phrase.

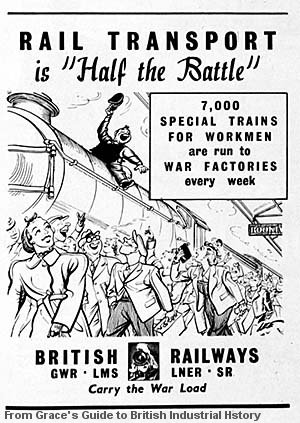

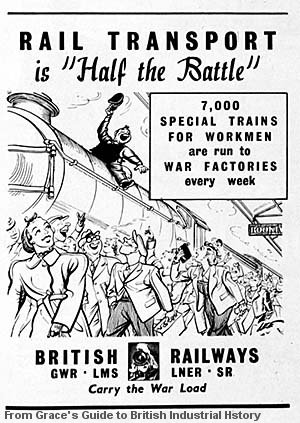

Above is another wartime notice and this one, as does that below, shows how the Big Four railway companies came under the singular title 'British Railways' which, as explained earlier, was nothing to do with the post 1948 British Railways although, it must be said, the use of the title for the nationalised rail network was in all probability more than mere coincidence. As already explained, these posters and notices were intended as morale boosters and often showed cheerful and jovial people as indeed does that above. The locomotive is an obvious representation of an LNER example but backgrounds were always generalised; they did not need to show specific locations to convey their messages and to do so may have posed security risks.

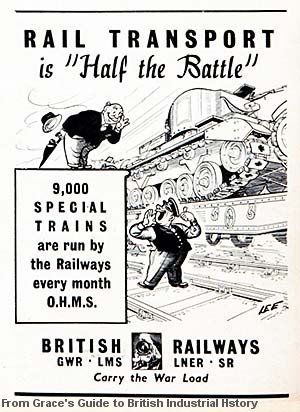

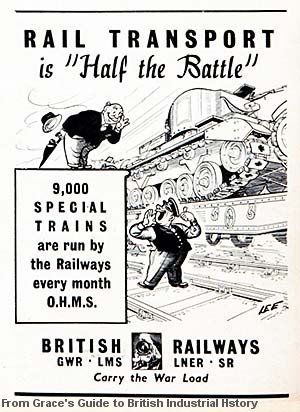

To the right is just one more example and this one, as before, shows just how busy the railways were during wartime and has a specific reference to military traffic. As ever, cheerful looking characters are depicted. There is another aspect to these notices and posters which may not be immediately obvious; they show cheerful people all getting along together irrespective of class or status. War, it is often said, is the great social leveller. O.H.M.S stood for On His Majesty's Service. Note that details are very realistic; track; tank, Warflat wagon; clothing. This, too, was deliberate in order to convey the impression of real life. No doubt this worked but these pictorials were never as popular as the more colourful and cartoon-like posters which have become synonymous with railway, and especially, tube stations.

To the right is just one more example and this one, as before, shows just how busy the railways were during wartime and has a specific reference to military traffic. As ever, cheerful looking characters are depicted. There is another aspect to these notices and posters which may not be immediately obvious; they show cheerful people all getting along together irrespective of class or status. War, it is often said, is the great social leveller. O.H.M.S stood for On His Majesty's Service. Note that details are very realistic; track; tank, Warflat wagon; clothing. This, too, was deliberate in order to convey the impression of real life. No doubt this worked but these pictorials were never as popular as the more colourful and cartoon-like posters which have become synonymous with railway, and especially, tube stations.

Local Defence and the GHQ line

With the passage of time, many people think of WWII as being a period or aerial warfare. Insofar as Britain was concerned air raids and, later in the war, Hitler's V weapons, were very much the face of the war. However, until Hitler turned his attentions to Russia and Operation Sealion, the planned invasion of Britain, was shelved, the threat of a seaborne invasion was very real. There was also the problem of enemy agents entering Britain, either by U-boat or, more usually, by parachute. Further, the matter of crews, if they survived, of crashed enemy aircraft was another aspect of the war for which contingencies had to be in place. The eyes and ears, as it were, for many of these possible threats was the Home Guard.

Much of Britain's coastline, especially the south and east coasts, was heavily defended but the south and east had a further line of defence running inland of the coast. This was the GHQ line (General Headquarters line); a defensive line stretching from near Highbridge, Somerset, eastwards to London, which it encircled on three sides, then northwards through Essex, Cambridgeshire, West Norfolk and eventually ending near Richmond, Yorkshire. Slowly becoming forgotten with the passage of time, the purpose of the GHQ line was not to stop an invasion force as many people think, but to hinder its advance to allow time for reinforcements to position themselves. Where possible and where appropriate, the GHQ line made use of natural obstacles such as rivers but much of it consisted of anti-tank ditches and other obstacles such as tank traps. The GHQ line was heavily guarded by Pillboxes, blockades, mortar and gun emplacements and where it crossed bridges, railway lines etc. explosives were often laid to further hinder an invasion force.

Cambridge was one of the few settlements of any size to actually sit on the GHQ line. The line, as we will call it, approached Cambridge from the south via the grounds of Audley End House, Great Chesterford (north of which it cut through the course of the abandoned Newmarket - Chesterford railway) and Stapleford. From the latter, The line turned north-east to cross Hinton Way and then what is today the A1307 road at a point some 200 yards from the present day Park & Ride carpark and on the Cambridge side. It then crossed Worts Causeway, Queen Edith's Way and then along the east side of Mowbray Road where Hulatt Road now is, then across Cherry Hinton Road to run parallel with Perne Road. Having crossed Birdwood Road, it then veered east-north-east at what is now the junction of Ancaster Way and Tiverton Way to cut through the abandoned trackbed of the pre 1896 Newmarket railway at a point just west of Brookfields. From there, the line then crossed the present Newmarket railway at a right angle and at a point just north-west of the Tins footbridge (this bridge being adjacent to the engine shed of the former Norman Cement works). The line then crossed Coldham's Lane and what is now the south-west corner of Cambridge airport, through what is now the Keynes Road/Dudley Road housing estate before arriving at a point near Chesterton Junction. From there it followed the rivers Cam and Ouse to Ely, Littleport and up to the Wash before heading back inland through Lincolnshire and up to Yorkshire. The Wash was the only point at which the GHQ line made use of the coast.

Today, the infilled anti tanks ditches between Stapleford and Worts Causeway can still be picked out from the air. Much of eastern Cambridge has seen all traces of the line obliterated by building and, around the former cement works, quarrying. Many pillboxes and gun emplacements were removed postwar but nevertheless a number still remain. Some ditches, especially in the Fens, were retained for use as drainage ditches while the remains of road blocks and tank traps can still be found here and there if one is determined enough to look and knows what to look for.

The GHQ line ran immediately east of the main north - south railway through Cambridge. As we have already seen, the railway was vital to the war effort, as were railways everywhere, and Cambridge also had a number of other industries vital to the war effort. To this end, Cambridge was protected by two further anti tank ditches; one running from just north of Chesterton Junction and east of the railway, ie from the river, round the north of Cambridge to a point just north-east of Huntingdon Road and another from near the junction of Madingley Road and Grange Road south towards Grantchester. There were numerous road blocks and some 40 pillboxes throughout the city and at its perimeters. Too numerous to describe their locations in full here, many were close to the railway and of note were roadblocks on Long Road, west of the bridge over the Bedford line; Hills Road at the south end of the bridge; Mill Road, east of the bridge; Coldham's Lane, east of the bridge; Paper Mills Road (Newmarket Road), east of the bridge; Fen Road, east of the level crossing at Chesterton Junction. The were also pillboxes at Chesterton Junction, west of the railway; Barnwell Junction, again west of the railway; Coldham's Road, in the V formed by the main line/Newmarket line junction.

Photo by Keith Edkins reproduced from Geograph under creative commons licence

The pillbox seen above sits close to the River Cam and the railway at Fen Road level crossing, Chesterton Junction. The overhead wires of the railway can be seen in the background. This pillbox is a Type 22, one of the standard designs seen across the country. It was part of the GHQ line and would have been manned by D Company Home Guard, headquartered in Chesterton.

Photo by Keith Edkins reproduced from Geograph under creative commons licence

Above is a Type 24 pillbox; another standard design and a thicker-walled version of the Type 22. This example sits on the down side of the railway between Chesterton Junction and Waterbeach, at a point where the river bends to run very close to the railway. This pillbox was also part of the GHQ line and both railway and river are behind the photographer. Both pillboxes were photographed in 2008. Near the second location is a surviving spigot mortar base; Spigot mortars being a type of anti tank weapon and their concrete bases remain common today.

There were also several Home Guard headquarters in Cambridge and those relevant to the railway were located at Mill Road, up side and north of the bridge (A Company Home Guard); Mill Road, up side and south of the bridge (G Company Home Guard); Hills Road, up side and south of the bridge (B Company Home Guard); Milton Road, east side and south of the St Ives line (E Company Home Guard).

The End Of The War and Nationalisation

On 30 April 1945, in his Berlin bunker, Adolf Hitler committed suicide and Germany signed an unconditional surrender one week later; the European theatre of the Second World War thus drew to a close with 8 May 1945 being VE Day (Victory in Europe). But while the bombing ceased and blackout restrictions were lifted, life by no means returned to normal overnight. Prisoners of war (POWs) remained in detention for the time being and rationing did not finally end until 1955.

Not only were there thousands of troop movements, equipment had to be moved and disposed of while British industry and domestic needs had to get back on their feet. To quote another familiar phrase from wartime; 'And still the railways carried on'. As elsewhere, the railways of Cambridge were as busy as ever carrying coal, oil, food, military equipment, rubble from bomb sites and other now-almost-forgotten commodities such as components for prefabricated housing (prefabs) for people who had lost their homes through bombing. In Cambridge, one of the best known and last surviving estates was that east of Coleridge Road, in the Golding Road area. It survived until 1974 when it was replaced by modern housing.

Cambridge was also the scene of much scrapping of surplus military equipment. Land west of the airport around what is now Barnwell Road (which was not made a through road linking Newmarket Road with Coldham's Lane until relatively recent times) was used for the dismantling of redundant aircraft and the scrapyard of Richard Duce was very busy scrapping dismantled aircraft, bombs, shells and other equipment. A record survives of the LMS Mill Road Wharf (the former Midland Railway sidings) being proposed as a 'stacking ground' for Richard Duce during 1946 although it is not known if this actually occurred.

Further along Coldham's Lane, near its Cherry Hinton end, the scrapyard of Messrs Rich also dealt with ex-military equipment, mostly vehicles. Road tankers formerly used on aerodromes and other military installations became a common sight in farmyards around Cambridge and other parts of the country. A significant amount of this redundant equipment, as said, was transported by rail.

With the end of the war, many of the aerodromes became superfluous and were gradually closed down from 1946 onwards. This, too, involved yet more movement of equipment by rail but with the onset of the Cold War some bases were retained by both British and American forces. Of the aerodromes which did close in the years immediately following the war, traces of many are now difficult to discern but at others enough remains to stand as ghostly reminders of those who not only did their duty but also of those who did not survive to see the freedom they so bravely fought for.

For all those who gave their lives in pursuit of freedom in all wars:

We will remember them

Click here to continue Part 4:

The Second World War and Nationalisation

Furthermore, in many countries Jews were mistrusted and at best merely tolerated by the majority of populations and Britain was no exception. This had been the case for centuries. For example, Britain expelled her Jews in the 13th century and it wasn't until the 19th century that Jews, in spite of Benjamin Disraeli, were permitted to sit in parliament. In the 1930s Britain, as elsewhere, was suffering from The 'Great Depression' and as we have already seen Cambridge had its share of poverty and unemployment. Given the anti-semitism which existed and the poverty and unemployment caused by the depression, there was some unrest in Britain over the taking in of refugees. As war clouds gathered there was further unrest because the Jewish refugees were, after all, largely Germans. Once war was declared these [adult] refugees became, by default, enemy aliens and so, for fear of spies, on Churchill's order, they were sent to an internment camp. This internment involved enemy aliens over 16 years old and as the Kindertransport children were up to 17 years old, some of them were also involved. A total of 281 refugees from Cambridge were interned on the Isle of Man.

Furthermore, in many countries Jews were mistrusted and at best merely tolerated by the majority of populations and Britain was no exception. This had been the case for centuries. For example, Britain expelled her Jews in the 13th century and it wasn't until the 19th century that Jews, in spite of Benjamin Disraeli, were permitted to sit in parliament. In the 1930s Britain, as elsewhere, was suffering from The 'Great Depression' and as we have already seen Cambridge had its share of poverty and unemployment. Given the anti-semitism which existed and the poverty and unemployment caused by the depression, there was some unrest in Britain over the taking in of refugees. As war clouds gathered there was further unrest because the Jewish refugees were, after all, largely Germans. Once war was declared these [adult] refugees became, by default, enemy aliens and so, for fear of spies, on Churchill's order, they were sent to an internment camp. This internment involved enemy aliens over 16 years old and as the Kindertransport children were up to 17 years old, some of them were also involved. A total of 281 refugees from Cambridge were interned on the Isle of Man. The Is Your Journey Really Necessary? notice is seen to the right. This, like others, appeared in many different forms with the most well known being the colourful and slightly humourous versions in poster form. Those relevant to the railways appeared on stations, in publications and sometimes in trains. The idea was two-fold; to convey a serious message and to help keep up morale. This notice was very clever in its design; the English text was at the bottom and as people would naturally read from the top downwards they would be reminded of Britain's non-English speaking allies. The inclusion of Russia indicates the poster was produced after Germany had attacked that country in Operation Barbarossa, June 1941. As we will later see, 'British Railways' was nothing to do with the not then nationalised British Railways. As in WWI, in WWII the railways came under government control and the title was simply a way of referring to all the railway companies collectively. It also had morale-boosting value as it gave a sense of unity.

The Is Your Journey Really Necessary? notice is seen to the right. This, like others, appeared in many different forms with the most well known being the colourful and slightly humourous versions in poster form. Those relevant to the railways appeared on stations, in publications and sometimes in trains. The idea was two-fold; to convey a serious message and to help keep up morale. This notice was very clever in its design; the English text was at the bottom and as people would naturally read from the top downwards they would be reminded of Britain's non-English speaking allies. The inclusion of Russia indicates the poster was produced after Germany had attacked that country in Operation Barbarossa, June 1941. As we will later see, 'British Railways' was nothing to do with the not then nationalised British Railways. As in WWI, in WWII the railways came under government control and the title was simply a way of referring to all the railway companies collectively. It also had morale-boosting value as it gave a sense of unity.

To the right is just one more example and this one, as before, shows just how busy the railways were during wartime and has a specific reference to military traffic. As ever, cheerful looking characters are depicted. There is another aspect to these notices and posters which may not be immediately obvious; they show cheerful people all getting along together irrespective of class or status. War, it is often said, is the great social leveller. O.H.M.S stood for On His Majesty's Service. Note that details are very realistic; track; tank, Warflat wagon; clothing. This, too, was deliberate in order to convey the impression of real life. No doubt this worked but these pictorials were never as popular as the more colourful and cartoon-like posters which have become synonymous with railway, and especially, tube stations.

To the right is just one more example and this one, as before, shows just how busy the railways were during wartime and has a specific reference to military traffic. As ever, cheerful looking characters are depicted. There is another aspect to these notices and posters which may not be immediately obvious; they show cheerful people all getting along together irrespective of class or status. War, it is often said, is the great social leveller. O.H.M.S stood for On His Majesty's Service. Note that details are very realistic; track; tank, Warflat wagon; clothing. This, too, was deliberate in order to convey the impression of real life. No doubt this worked but these pictorials were never as popular as the more colourful and cartoon-like posters which have become synonymous with railway, and especially, tube stations.

Home Page

Home Page