CATLOW QUARRIES[Source: Alan Young]

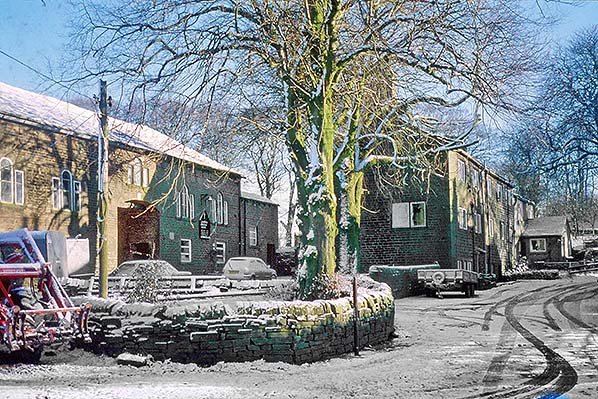

Catlow Quarry was first worked in the 1830s by Robert Hartley and Richard Elliott. The earliest edition of the Ordnance Survey 1:10,560 map of 1848 shows Catlow Quarry immediately east of Southfield Lane and south of the Shooters Inn (now the Shooters Arms). Several other small sandstone quarries are also shown in the surrounding area on this map. Catlow was a source of excellent stone for building and paving, described as fine-to-medium current-bedded massive and flag sandstone up to 60ft in thickness. In the ownership of Benjamin Chaffer (b1815 – d1883) the quarry expanded rapidly and a new working was established west of Southfield Lane, leaving the local blacksmith’s premises adjacent to the original quarry almost surrounded by excavations; if not actually established to cater for the quarry’s mechanical and equestrian requirements the quarry undoubtedly brought much business to the smithy.

Chaffer claimed that his stone had built ‘half of Liverpool’; it could be conveyed there by means of the Leeds & Liverpool Canal and (after it opened in 1849) by rail. The canal passed about two miles west of the quarries through what was to become the town of Nelson, and the opening of the railway established this name for the new town when its station was called after the nearby Lord Nelson inn. The quarry was the principal source of stone for building Nelson, a latecomer to the east Lancashire industrial scene which grew rapidly with cotton-weaving mills and sheds, terraced housing and a variety of civic, commercial and religious buildings after the mid nineteenth century. It might have been built of excellent stone, but the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner (1969) was disparaging about the town: ‘Nelson has no past and no architectural shape … Only the Parish Church keeps up a civic dignity’, and he felt that the town’s saving grace was the surrounding natural landscape. The town might have lacked architectural attraction but its residents in the 1930s were proud of their town; indeed only Southport was judged to be a cleaner and tidier Lancashire town. Catlow stone was of such high quality that it was even in demand overseas, with large quantities sent to South Africa. Whilst the nearby Clough Head colliery (OS Grid Reference SD 873372) was using a ‘tram road’ down to the railway near Nelson by the late 1840s (and Town House Quarry used it later), it is perhaps surprising that Catlow stone was always conveyed from the quarries by road. In 1884 the Chaffer family invested in a steam traction engine to take the stone downhill to Chaffers Siding, and whilst this beast caused amusement to local people as it emitted a ‘Chaffer! Chaffer! Chaffer!’ sound as it chugged along Barkerhouse Road its destructive impact was not so well received. To comply with a law then in force the vehicle had to be preceded by a man waving a red flag to warn of its approach, but in 1896 this legislation was repealed. The track from Catlow Quarries past Southfield Chapel was busy for some decades with carts taking the stone downhill to Brunswick Street in Nelson where it was conveyed by horse and cart to the numerous building sites in the town and to the canal. It passes close to the dam of Walverden Reservoir, constructed in 1867 using Catlow stone. Sandstone setts laid on the track to provide a stable surface can still be seen today. In the years immediately after the First World War the stone continued to be moved by horse and cart; eight large Belgian horses were kept to transport the stone in loads of up to 7 tons, one horse leading and another following to prevent the cart from gathering momentum on the downhill slope.

Between the surveying for the OS maps of 1891 and 1912 the quarry west of Southfield Lane was greatly extended, and to accommodate its expansion part of the track from Southfield Lane down to Southfield Chapel and Southfield House Farm was diverted along the course of an existing footpath through Todd Field to leave Southfield Lane at the quarry office immediately north of Mount Pleasant; another track already left Southfield Lane at this point leading downhill to Lower Row, Southfield Farm and Southfield Fold Farm. A further diversion of the track to the chapel took place c1914 to avoid a new northward extension of the quarry. In 1902 Nelson Corporation built a smallpox hospital in the southern end of the quarry, east of Southfield Lane and close to the hamlet of Catlow. A site about 200yd from the smallpox hospital, west of Southfield Lane was used for the corporation’s scarlet fever hospital. At the height of their importance in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Catlow Quarries were of great economic benefit to the area, employing over 200 men. Some of the workforce lived within easy walking distance, as seen in the 1891 Census. In five of the six Mount Pleasant cottages there were quarry workers; one cottage accommodated three, and another two, quarrymen. One of the foremen lived in Mount Pleasant, and one quarry employee was described as a stone dresser. The quarry office was located adjacent to Mount Pleasant. Similarly five cottages in Catlow Row were occupied by employees of the quarries, two described more specifically as a mason and a stone breaker. Referring to the workers as quarry ’men’ overlooks the employment of children. Peter Smith, a local farmer recalls that his great-grandfather was a quarryman and at the age of seven his grandfather began work there at the expense of schooling, leaving him unable to read and write; the child was to work at the quarry for almost 60 years, continuing as a night watchman until the quarry closed, then dying that same year of silicosis, a disease that claimed the lives of many quarry workers.

Life for the quarrymen was difficult and at times work and pay ceased altogether when they were ‘frozen out’. At an altitude of nearly 900ft during some bad winters with persistent frost or snow the quarrying came to a halt, sometimes for weeks on end. In the 1840s one such episode temporarily deprived Henry Elliott (son of Richard who first worked the quarry) and his brothers Francis and John who were also Catlow quarrymen of their work and income. However Henry’s son, Thomas, had the good fortune during this ‘freeze out’ to discover two shilling pieces embedded in the frozen ground while on his way to the post office near Lomeshaye Lane top. The family’s simple diet of porridge could suddenly be replaced with a feast! Quarry life had its lighter moments. Apparently, on at least one occasion advantage was taken of a gullible young worker who would be instructed to paint a crane in the quarry. The jib was about 100ft in length and the young man would make his way to the far end of the jib armed with his brush and paint and start work. Meanwhile another quarryman would begin painting halfway along the jib and paint back towards the crane, leaving 50ft of wet paint for his junior colleague to have to scramble across to reach safety. On their Sabbath day of rest (after chapel?) the quarry workers and other local men would gather at the Shooters for a session of ‘Road Bowling’ along the two-mile moorland lane to Coldwell Inn (on the way to Hebden Bridge via the ‘Widdop Road’). The bowl was a lump of stone shaped and angled for throwing round corners, and whoever completed the journey with the fewest throws was the winner. ‘Knur and Spell’, a variation on road bowling, was also played from the Shooters to Coldwell, but across the fields. The ‘Knur’ (a stone probably about the size of a golf ball) was thrown in the air and clouted with the ‘Spell’ (a shaft of wood). Undoubtedly, money changed hands as part of these games.

After World War 1 the demand for building stone declined as brick proved to be cheaper and more fashionable; brickworks in Accrington supplied much of the North-West with its plum red product which is not to everyone’s taste. Even in Nelson itself, with excellent stone on its doorstep, inter-war estates were brick-built; however they were usually given a rendered finish and did not clash dramatically with the earlier stone terraces. Demand continued to fall and the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 with the call-up of able-bodied men spelt the end of stone extraction at Catlow. In the ownership of William F Chadwick the quarry closed in 1939 or 1940; sources differ on the date. Only a small area the most easterly end of the quarries was worked after World War 2 and stone is still extracted in limited quantities. The OS map of 1932 shows that the smithy beside the quarries on Southfield Lane had closed and been demolished. When the quarries closed the office building close to Mount Pleasant, with its commanding view westwards over Nelson and Barrowford became an ARP (Air Raid Protection) lookout post. The ARP warden would spend the night on duty before walking downhill in the morning to milk his cattle and resume other farming tasks. The buildings, stone-cutting machines and cranes in Catlow Quarries were intact as late as 1942. During the war the quarries were used for training the Home Guard and youngsters would seek out stray hand-grenades as playthings. A ‘pill box’ was constructed during the war close to Southfield Lane at the southern end of the quarry, on a bluff next to the former smallpox hospital, with a clear view across the valley of Catlow Brook as far as Lane Bottom and Haggate. The pill-box remains in place today, but nothing is left of the hospital which, having closed, would be used for some years to house poultry. Structures in the quarries were demolished in the late 1940s on the orders of the local council following an accident in which a young girl playing there was injured when she fell from a crane. The demolition work was not thorough as the base of a crane remains in the east quarry and west of Southfield Lane huge stone blocks which carried a steam-operated saw are still in place. In the mid 1960s Catlow Quarries provided ‘waste’ rock for use in the construction of the Padiham Bypass (A6068) whilst mud from the construction site (referred to locally as ‘sludge’) was conveyed to the quarries to be dumped along with waste from households, hospitals, butchers and other sources. In 1978 the revival of quarrying became a distinct possibility

when an application was made to remove rubble to be used as footings for the M65 motorway (Blackburn to Colne), but this did not go ahead owing to local concerns about noise and disruption..

In 2003 the Southfield Conservation Area was established to preserve the character of this rural-industrial landscape most of whose buildings are pre-Victorian; it includes the two hamlets of Southfield, Mount Pleasant cottages and the old quarry office, several farm buildings and the hamlet of Catlow, as well as the abandoned Catlow Quarries which represent the principal Victorian contribution to the landscape. The chapel, officially Southfield Methodist Church, was established in 1797 and is still an active place of worship; John Wesley stayed and preached on several occasions in the hamlet between 1784 and 1790. Despite the new Conservation Area status an application was made in 2005 for a development of over 100 holiday chalets and associated facilities in Catlow Quarries, on both sides of Southfield Lane. An ‘ecology centre’ was to be included - no doubt to silence objectors to the ecological insensitivity of the whole scheme. The application was withdrawn when the deadline for an environmental audit could not be met, but the project bounced back in 2007 in a more restrained form for 25 chalets to be constructed in the western quarry but nothing east of Southfield Lane. Some ground preparation has been carried out and a screen of alders has been planted on Southfield Lane, but nine years later no chalets have appeared. Just outside the Conservation Area, as noted above, the field bordered by Southfield Lane and Delves Lane (historically known as Main Delves) on Crawshaw Hill is formed of hummocky terrain as a result of numerous shallow pits being dug to remove coal. These were worked in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and were abandoned before the coming of the canal and railway. Each hole was dug and extended a short distance sideways until it became unstable and was abandoned; the cross-section of these workings was bell-shaped, thus the descriptive name ‘bell pits’. This method of mining was found elsewhere in England where coal seams were close to the surface (for example in the Town Moor, Newcastle upon Tyne) but there can be few places where the evidence of this primitive mining is clearer than at Southfield. Dedicated to Peter K Smith (5 February 1934 - 9 January 2017) whose recollections, some of them written in a journal, were shared with the author towards the end of 2016. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

See also Chaffers Siding (feature) Catlow Quarries Gallery 1  Before sandstone was extracted on a large scale at Catlow there were many small coal pits nearby (known as ‘bell’ or ‘beehive’ pits because of their shape in cross section) worked in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and possibly earlier. This uneven ground in the field known as Main Delves, seen here in December 2016, is clear evidence of shallow coal pits. Just above the centre of the picture is Barkerhouse Road leading westwards downhill into the town of Nelson, and Catlow sandstone was carried down this road to the stone works at Chaffers Siding. Pendle Hill (1927ft) is on the horizon.

Photo by Alan Young

This uneven ground in the field known as Main Delves is evidence of shallow coal pits abandoned for more than two centuries. The view is westwards towards Nelson and Pendle Hill (December 2016).

Photo by Alan Young

On Crawshaw Hill, Southfield, this area of chaotic relief is evidence of former coal pits. The hollows correspond to the ‘bell pits’ dug over two centuries ago and the ridges were formed by spoil dumped around the pits; the pits themselves have been partially infilled as they collapsed when they were abandoned and natural weathering will have continued the process before the grass was established. The view in December 2016 is eastwards. The field is known as Main Delves and although it is mostly turned over to sheep pasture, it also includes the distant belt of deciduous trees. The evidence of the bell pits ends at a drystone wall immediately beyond the trees.

Photo by Alan Young  Dairy cattle are the only northbound traffic along Southfield Lane past the Shooters Arms on 25 July 1992. The Shooters Inn, as it was formerly known, dates from 1660 and served travellers on the King’s Highway between Burnley and Colne (before nearby Nelson existed) as well as local farmers and quarrymen. In the distance is Mount Pleasant, a terrace of cottages adjacent to Catlow Quarries and formerly occupied by quarrymen and their families.

Photo by Alan Young

The hamlet west of Catlow Quarries is seen on 25 February 1991, looking east; the quarry is immediately beyond the trees in the distance. In this part of Southfield which includes Southfield House (to the right, off the photo) and Nos. 4 to 7 Southfield Cottages, residents have historically worked in farming, quarrying and weaving; the upper of the three floors in the cottages were ‘loomshops’. Southfield Methodist Church, usually called ‘Southfield Chapel’ is set back on the left. It is still (2017) an active Methodist place of worship.

Photo by Alan Young

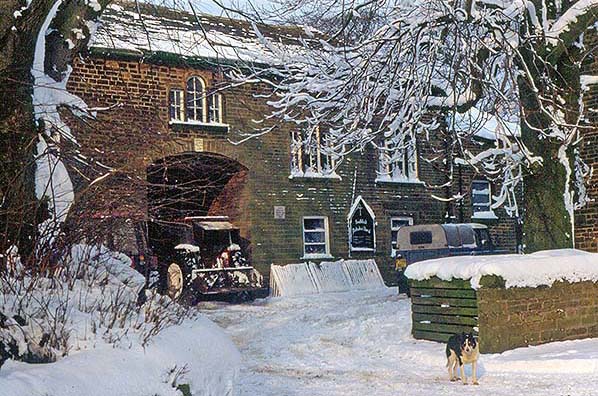

Southfield Methodist Church is seen here in the snow on 25 February 1991. Southfield House is behind the camera. What is locally called Southfield Chapel was built in 1797 by William Sagar of Southfield House who was a friend of John Wesley, the ‘founder’ of Methodism. On several occasions Wesley stayed and preached in this hamlet; a plaque, on the outer wall of the ‘chapel’, records that in 1786 Wesley preached at Southfield. The building incorporates a barn on the ground floor and the chapel above with space for about fifty worshippers. The Venetian windows add a suitably Classical character as nonconformists preferred the dignity of Classicism to what they considered the fussiness of Gothic architecture. In a region where Primitive and Independent Methodism and the Inghamites (a local denomination with Methodist characteristics) also provided places of worship, Southfield was a Wesleyan chapel. It undoubtedly welcomed many Catlow quarrymen and their families and in 2017 remains an active place of worship despite the gloomy prediction in 1899 by a historian of local Methodism that its days were numbered.

Photo by Alan Young

Southfield House and chapel and the former Catlow Quarries are behind the camera in this westward view in December 2016. Sandstone blocks and flagstones from the quarries were carried on carts down this this track into the town of Nelson. The stone setts provided a firm surface for the heavy vehicles. Nelson was a latecomer to the industrial landscape, expanding rapidly from the late 1840s when the railway arrived. Until World War 1 almost every building in the town was constructed of stone from Catlow Quarries.

Photo by Alan Young  The stone from Catlow Quarries that was to be dispatched by rail was conveyed down Barkerhouse Road to Catlow Stone Works and the adjacent Chaffers Siding. This distinguished building was passed on Barkerhouse Road. It was the home of Amos Nelson (1860-1947), a wealthy cotton manufacturer and was built c1900 on what was then the eastern fringe of Nelson’s built-up area. In later years the building was Springhill Home for the Blind and it ended its life as Great Marsden Hotel. This view of 3 June 2008 shows the derelict building between its sale by auction in 2006 and demolition in November 2008. The site is now occupied by Marsden Manor nursing care home, a tasteful building in a The stone from Catlow Quarries that was to be dispatched by rail was conveyed down Barkerhouse Road to Catlow Stone Works and the adjacent Chaffers Siding. This distinguished building was passed on Barkerhouse Road. It was the home of Amos Nelson (1860-1947), a wealthy cotton manufacturer and was built c1900 on what was then the eastern fringe of Nelson’s built-up area. In later years the building was Springhill Home for the Blind and it ended its life as Great Marsden Hotel. This view of 3 June 2008 shows the derelict building between its sale by auction in 2006 and demolition in November 2008. The site is now occupied by Marsden Manor nursing care home, a tasteful building in atraditional style. Photo by Alan Young Click here for Catlow Quarries Gallery 2

Home Page Home Page

|

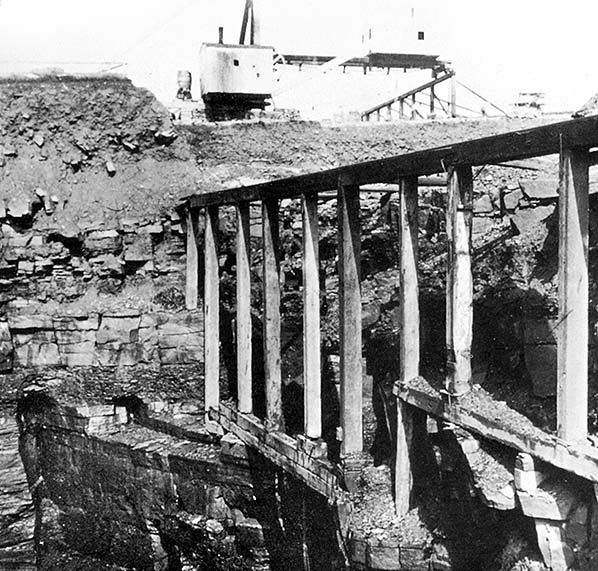

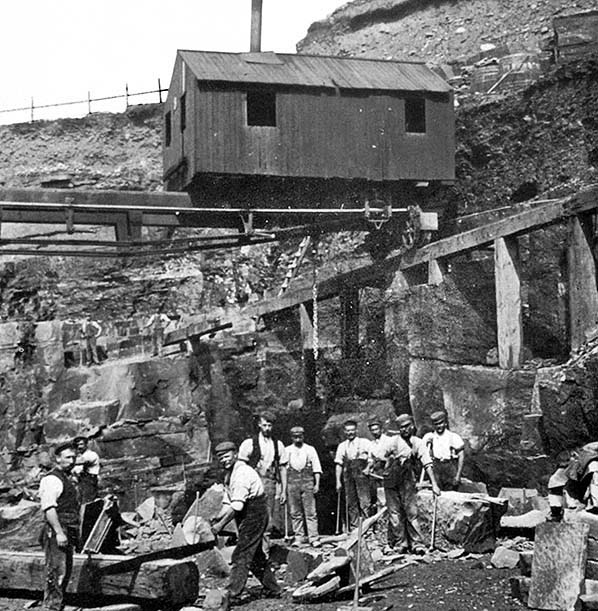

An undated photograph taken within Catlow Quarries.

An undated photograph taken within Catlow Quarries. 1930 1: 10,560 OS map. By 1930 Catlow Quarries had expanded to their fullest extent both east and west of Southfield Lane. Stone was conveyed from the quarries to Chaffers Siding via Barkerhouse Road which leaves Southfield Lane north-west of the Shooters Arms, and to the town and canal via Southfield House. Catlow Quarry office was at the northern end of Mount Pleasant cottages. The relatively isolated location prompted Nelson Corporation to build small hospitals, one within the quarry for victims of smallpox within the quarries and another for scarlet fever patients on the opposite side of Southfield Lane just outside the quarries. Main Delves field (not named) containing numerous abandoned bell-pits where coal was extracted before the Industrial Revolution is on Crawshaw Hill, north of the Shooters Arms. Only the small, most easterly section of Catlow Quarries has been worked since World War 2. Click

1930 1: 10,560 OS map. By 1930 Catlow Quarries had expanded to their fullest extent both east and west of Southfield Lane. Stone was conveyed from the quarries to Chaffers Siding via Barkerhouse Road which leaves Southfield Lane north-west of the Shooters Arms, and to the town and canal via Southfield House. Catlow Quarry office was at the northern end of Mount Pleasant cottages. The relatively isolated location prompted Nelson Corporation to build small hospitals, one within the quarry for victims of smallpox within the quarries and another for scarlet fever patients on the opposite side of Southfield Lane just outside the quarries. Main Delves field (not named) containing numerous abandoned bell-pits where coal was extracted before the Industrial Revolution is on Crawshaw Hill, north of the Shooters Arms. Only the small, most easterly section of Catlow Quarries has been worked since World War 2. Click  Workers photographed in Catlow Quarries, probably in the 1930s.

Workers photographed in Catlow Quarries, probably in the 1930s. A group of quarrymen at Catlow circa 1900. Please let us know if you can identify any of the men.

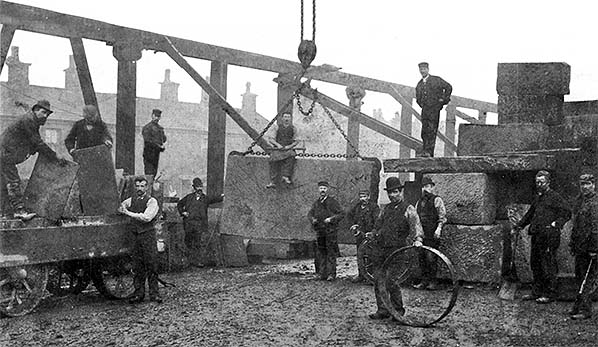

A group of quarrymen at Catlow circa 1900. Please let us know if you can identify any of the men. Stone from Catlow Quarries to be sent onward by rail was carried via Barkerhouse Road to Catlow Stone Works beside the line between Nelson and Colne. Here it was cut and shaped before a travelling crane loaded the stone onto wagons standing on Chaffers Siding. This view dating from about 1900 is looking north-west with Chapel Street, Nelson, in the background.

Stone from Catlow Quarries to be sent onward by rail was carried via Barkerhouse Road to Catlow Stone Works beside the line between Nelson and Colne. Here it was cut and shaped before a travelling crane loaded the stone onto wagons standing on Chaffers Siding. This view dating from about 1900 is looking north-west with Chapel Street, Nelson, in the background.