Introduction

These pages are primarily concerned with the Shipston-on-Stour branch as it became under the Great Western Railway and British Railways Western Region. This cannot be realistically done however without providing some history of its predecessor, the horse-drawn Stratford and Moreton Railway, ‘the tramway’. This section covering the tramway has been written purely as a relatively brief overview and rather more intense histories can be found via the Sources and further reading section below. There are a number of myths and unknowns surrounding the tramway and some attempt has been made herein to describe these and when possible provide some form of conclusive evidence.

Background

Britain is a collection of islands and around its coastline are ample provisions of harbours, either natural or man-made, along with estuaries giving access to inland areas via rivers insofar as rivers were navigable. Until the coming of the railways and metalled roads, coastal shipping was the primary means of transporting goods along with rivers and canals. While vessels could transport large quantities of goods, this method was painfully slow and was therefore unsuitable for fresh produce, fish and meat unless preserved by processes such as drying and salting. Such commodities were expensive and beyond the means of many. Most people therefore had to depend upon produce obtainable locally and\ or which they could grow themselves. In most cases this was seasonal and weather dependent. The transportation of coal and minerals was also a problem largely reliant upon coastal shipping and inland waterways. The problem here was that rivers and canals were not always navigable due to periods of drought and flooding.

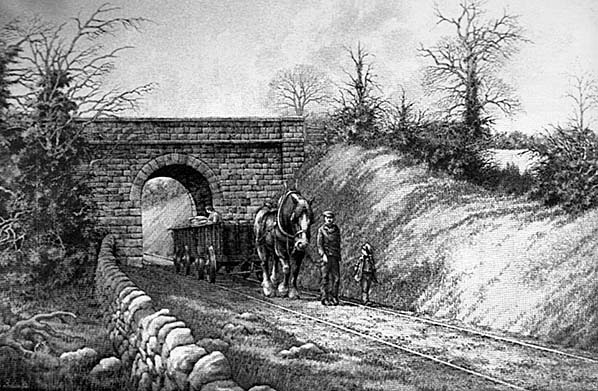

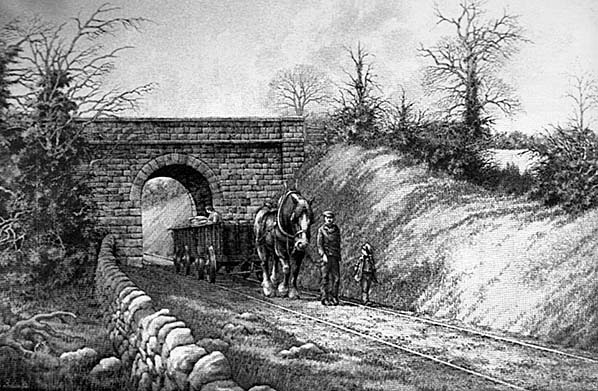

A painting by artist Sean Bolan showing a horse with two wagons, passing beneath Lemington Lane bridge with one passenger onboard. The location is a little under one mile north of Moreton-in-Marsh on the section which became part of the Shipston-on-Stour branch. The artist has depicted the bridge in as-designed by engineer Rastrick condition. It would have been rebuilt, possibly to accommodate Mr Bull's passenger service which used a conventional railway carriage of the time but certainly in preparation for what became the Shipston-on-Stour branch railway. Today the bridge no longer exists and the approach cuttings have been infilled and the road levelled. The site looks for all the world that it was once a level crossing. With due respect to the artists, some of those modern paintings are rather whimsical and show one horse hauling multiple wagons. Given the crude, plain bearings on these wagons, the rickety track and the gradients one might consider it unlikely one horse could haul anymore than a single loaded wagon.

A painting by artist Sean Bolan showing a horse with two wagons, passing beneath Lemington Lane bridge with one passenger onboard. The location is a little under one mile north of Moreton-in-Marsh on the section which became part of the Shipston-on-Stour branch. The artist has depicted the bridge in as-designed by engineer Rastrick condition. It would have been rebuilt, possibly to accommodate Mr Bull's passenger service which used a conventional railway carriage of the time but certainly in preparation for what became the Shipston-on-Stour branch railway. Today the bridge no longer exists and the approach cuttings have been infilled and the road levelled. The site looks for all the world that it was once a level crossing. With due respect to the artists, some of those modern paintings are rather whimsical and show one horse hauling multiple wagons. Given the crude, plain bearings on these wagons, the rickety track and the gradients one might consider it unlikely one horse could haul anymore than a single loaded wagon.

At the turn of the nineteenth century roads were still little more than dirt tracks, often muddy at some times of the year and rutted at others. We tend to think of highwaymen as a medieval problem but they were still active into the nineteenth century, predominantly around the major cities and especially London; the victims usually being lone travellers. Nevertheless the problem remained across the more populous areas of the country and made the transporting of goods by road a risky business. It is from highwaymen that the expression ‘Highway Robbery’, meaning something excessively priced, originated. Macadam, a name derived from John McAdam, roads did not appear until circa 1820 with the first such road reputedly being Marsh Road, Ashton Gate in Bristol. Macadam roads were a vast improvement on the dirt tracks, being made up from stone slabs vertically positioned, with the voids in between filled by small stones. The idea was that cart wheels would compress the stones into a near solid surface but they were far from perfect. Nevertheless Macadam roads persisted until the arrival of the road motor vehicle from the late nineteenth century when it was found that the relatively faster speeds created clouds of dust. In 1902 a Swiss, Dr. Ernest Guglielminetti, came up with the idea of using coal tar from gasworks to bind road surfaces, thereby ridding of the dust problem. At around the same time, Welshman Edgar Purnell Hooley was walking in Denby, Derbyshire and noticed a stretch of hard, smooth, dustless road which had been created by accident when a barrel of tar had been spilled and covered with slag. Hooley realised the potential and in 1902 patented a mix of tar and aggregate for use as a road surface. The following year, Hooley, following some tweaks to the ‘recipe’, formed the Tar Macadam Syndicate of which its trade name is today very familiar - Tarmac. The world's first Tarmac road was Radcliffe Road in Nottingham and the use of this product became widespread from circa 1920, effectively giving us the roads we are familiar with today. Cobbled roads had existed for a very long time (Roman roads were generally stone paved) but were impractical for anything more than short local roads and did not really come into their own until it became possible to infill with tar. They were also hazardous and still are in wet and icy conditions.

The transformation of roads into something practical and in theory usable at all times, was long after the creation of the Stratford and Moreton Railway which was the legal title that appeared as such on company seals. At least one of the seals has survived. However, this railway was and historically is commonly referred to as the ‘Stratford and Morton Tramway’ and the ‘tramway’ term is used in this work for reason of avoidance of any possible confusion with other railways in the area; in particular the section which ultimately became the Shipston-on-Stour branch of the GWR and British Railways.

Some form of guided transport had existed for long time previously, arguably back to Roman times when ruts formed in the surface of Roman roads by carts were found to act as a crude form of guideway. It was heavy industry though, which needed to shift large and heavy quantities of coal for example, which gave birth to what we now know as railways. Various terms were used in Britain; tramroad, tramway, railroad and of course railway; all without a hyphen. There was also the ‘plateway’, again with or without a hyphen, which used flanged rails rather than flanged wheels. While these plateways did the job they were designed to do, notwithstanding frequent broken rails, they were not really suitable for anything more than the plodding horse-drawn or manpowered tubs known.

The surviving tramway bridge over the Avon at Stratford-upon-Avon, seen here in 2010. This view is facing north-west towards the terminus wharf where the preserved wagon is located. The house at the far end of the bridge was originally a toll house; this is how revenue was collected, it being payable by the operators of the horse-drawn wagons.

The surviving tramway bridge over the Avon at Stratford-upon-Avon, seen here in 2010. This view is facing north-west towards the terminus wharf where the preserved wagon is located. The house at the far end of the bridge was originally a toll house; this is how revenue was collected, it being payable by the operators of the horse-drawn wagons.

Photo by Richard Croft reproduced from Geograph under creative commons licence

The surviving tramway bridge over the Avon at Stratford-upon-Avon, seen here on 27 November 2018. This view is facing north-west towards the terminus wharf where extensive sidings fanned out, many by means of wagon turntables, both dead ahead and in the left background. The sidings served the two canal basins, one of which is now infilled, rather than the River Avon. The premises to the right of the toll house were a timber yard. The somewhat fragmented strips on the bridge deck are illuminated and presumably supposed to represent tramway rails

Photo by Vauxford. Reproduced from Wikipedia under creative commons licence

We now return to the aforementioned problem of inland transport. Enter one William James who has been described by one author as a somewhat ‘shadowy’ figure. James, born in Henley-in-Arden on 13th of June 1771 was well educated, a solicitor by profession and acted as a land agent and supervisor of country estates, notably for the Earl of Warwick. He was also a promoter of canals with an added interest in early railways and geology as well as being a colliery owner. James is also described by many as an engineer but in what particular field, if any, is unclear.

James was however a visionary and dreamed of an extensive linked canal and railway system including the never built ‘Central Junction Railway’ which he proposed would have connected Stratford-upon-Avon with London. Via his father, James inherited interests in inland waterways and became part of the management of the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal. He was also a shareholder of the Upper Avon Navigation, sometimes known as the ‘Warwickshire Avon’. James' vision of a linked canal and railway, or tramroad system would, had it been built, have been an early version of what we would today call an ‘integrated transport system’. In any case canals take a very long time to construct; for example the Leeds Liverpool Canal which took 47 years to complete. The James plan, had work commenced, would very likely have fallen victim to the massive and rapid expansion of the railway network which at the time was on the proverbial horizon. It is not clear precisely when James proposed his schemes for what in his opinion comprised ‘southern England’ but the ‘Central Junction’ part is known to have been mooted around 1820/ 1. By this time the then primitive contraptions that were steam locomotives had already made an appearance so quite why James proposed a network of linked canals and railways/ tramroads, the canal sections of which would have taken decades to complete, is by no means clear. Perhaps he was simply blinded by his faith in canals.

As things turned out, James was too much of a visionary and he became a bankrupt. There is some suggestion he was given a prison sentence in 1822 (bankrupts could be and often were given prison sentences) but either way being declared bankrupt at the time was considered a total disgrace and James was reduced, at least on paper, to the status of clerk with the Stratford and Moreton Railway Company. James moved to Bodmin, Cornwall in 1827 taking some of his visionary ideas with him. He died at Bodmin on the 10th of March 1837, reputedly after having contracted pneumonia as a result of a lengthy mail coach journey in the depths of winter.

At this point it is worth mentioning the names Stratford-upon-Avon and Moreton-in-Marsh. These have also been presented as ‘Stratford-on-Avon’ and ‘Moreton-in-the-Marsh’. The latter was a misdescription rectified in 1930, but occasionally still seen today. They can also been seen on period Ordnance Survey maps including in the somewhat clumsy title Stratford-on-Avon & Moreton-in-the-Marsh Tramway which seems to have been, on the part of the Ordnance Survey, more of a geographical title than anything else. Similarly, after the northern section of the tramway fell into disuse the Ordnance Survey chose to title this section the ‘Stratford-on-Avon and Longdon Road Tramway’.

At the time when the Stratford and Moreton Railway was still on the drawing board, James toured the country to examine the various railways and tramroads then in operation. This tour found him visiting Bedlington Ironworks, Northumberland where the works manager, John Birkenshaw, showed him his new invention of fish belly rails made from wrought iron and which could be produced in lengths up to 18ft. Until this time fish belly rails (see illustration) had been of cast iron and in lengths no longer than sleeper spacings - typically around 4ft. Cast iron has a high carbon content and while it can withstand high compressive forces it is brittle and cannot withstand sheer forces and sudden violent impacts. This was the reason why early railways and tramroad, including plateways, suffered so many broken rails and especially when steam locomotives were introduced to them; the 'grasshopper' locomotives with vertical cylinders linked to the wheels by vertical rodding. Wrought iron, on the other hand, is softer and therefore malleable. Steel has existed for a very long time but it was not until the invention of the Bessemer process, patented in 1856, that it was possible to mass produce steel in large quantities and with consistent quality. While wrought iron rails would be absolutely useless on the railways of today, James decided, rightly, that this type of rail would be suitable for the Stratford and Moreton Railway. During his tour James also came into contact with the Stephensons and as a result entered into some form or arrangement whereby steam locomotives would be supplied to James for his expansive ideas in southern England which he defined as being south of an imaginary line drawn between Liverpool and Hull. It can be safely assumed rails for the tramway came from Bedlington but whether this was all the rails, chairs etc is unclear. Some, at least, would have done with others possibly manufactured more locally.

What we today know as ‘standard gauge’ railway track, 4ft 8½in, did not exist under that terminology in the early 19th century and instead was, and to a degree still is, known as ‘Stephenson Gauge’. It is thought to have started out as 4ft 8ins with an extra ½in added subsequently in an attempt to reduce wear while leaving the gauge of wagons, then spelled ‘waggons’, unaltered. It is possibly for the same reason that Brunel's nominal 7ft broad gauge for the Great Western Railway actually appeared as 7ft ¼in. At the time, early 19th century, there was no standardised gauge as the railways, tramways/ tramroads then in existence were isolated affairs built to serve, primarily, heavy industry; gauge variations were therefore irrelevant. As railways began to spread beyond the industrial enclaves to form a countrywide network it was glaringly obvious a standardised gauge was an absolute necessity and probably because of the Stephensons’ involvement with many early railways their gauge became the ‘standard’ gauge. This was the reason for the eventual downfall of the Great Western Railway broad gauge - the loser of the so-called ‘Gauge War’.

The Railway Magazine of February 1935 stated that the Stratford and Moreton Railway was built to the 4ft gauge and converted to standard gauge at a later date. This is likely incorrect, but has unfortunately been perpetuated, and the railway was built either to 4ft 8in or standard gauge. Either way though, that difference of half an inch was probably irrelevant given how the tramway track was laid. While William James had surveyed the route its engineer was John Urpeth Rastrick, the Rastrick name being more familiar in the title Foster, Rastrick and Company of Stourbridge which built a number of early steam locomotives such as Agenoria and Stourbridge Lion to name just two. Rastrick, as tramway engineer, had some assistance from Thomas Telford and apparently also from Robert Stephenson but precisely what input these two men provided is not known. However, it is not unreasonable to suggest the support of Robert Stephenson resulted in the line being built to standard gauge. Remaining with the gauge subject, a drawing has survived of a flat wagon built by, or for, engineer Rastrick. While the specific purpose of this wagon is unclear, the drawing refers to it as a ‘testing carriage’. This drawing is to scale and from this, the gauge of the wheels can be calculated to be standard gauge or something very close to it, perhaps 4ft 8in. This acts to confirm the track gauge to which the tramway was built. One may therefore ask from where did The Railway Magazine obtain the 4ft gauge claim. The answer may lay with the Oxford Worcester & Wolverhampton Railway (OW&WR) which opened its station at Moreton-in-Marsh in 1853 and for reasons which are explained later took over the Stratford and Moreton Tramway. The OW&WR surveyed the tramway and undertook much remedial work including ‘regauging’. This necessitated the tramway ceasing operations for some weeks. Given the aforementioned evidence it would seem the regauging was nothing more than gauge correcting. The rails being mounted upon stone blocks with no cross ties would have meant the passage of wagons would, over time, cause the gauge to spread. There is some evidence that the OW&WR installed transverse sleepers on certain sections of the tramway as part of the same remedial works and this would also suggest gauge spreading had become a problem.

One prominent supporter of the tramway, arguably the most prominent, was John Freeman-Mitford, 1st Baron Redesdale (Northumberland) (1748 -1830) He was one time Speaker of the House of Commons and seated at Batsford Park, to the north-west of Moreton-in-Marsh. The Mitford name may be familiar to some readers. Many decades later the family produced what came to be referred to as ‘The Mitford Sisters’ of whom one, Unity Mitford (8 August 1914 - 28 May 1948), was to become a keen supporter of and allegedly a friend of Adolf Hitler. The 1st Baron was responsible for Redesdale Hall, Moreton-in-Marsh.

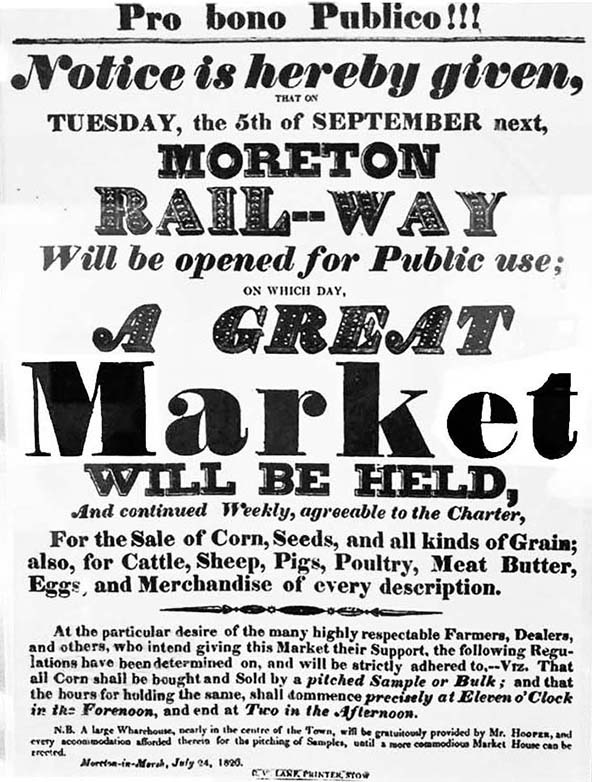

The Act allowing construction to begin was passed on 28 May 1821 but the use of steam locomotives was forbidden and this decision was possibly influenced by Thomas Telford who was known to be against any form of steam locomotion be it on road or rail. Telford had built up a good reputation for himself and such people were taken notice of by Parliament. It is the same today with considered experts usually being labelled as ‘Advisors to Number 10’ or some other similar wording to the same end. Authorised Capital was £35,000 with a five year time limit on completion of works. The five year stipulation was adhered to with the exception of the Shipston-on-Stour branch but the Authorised Capital was well exceeded - by some £45,000 according to a figure quoted at one point.

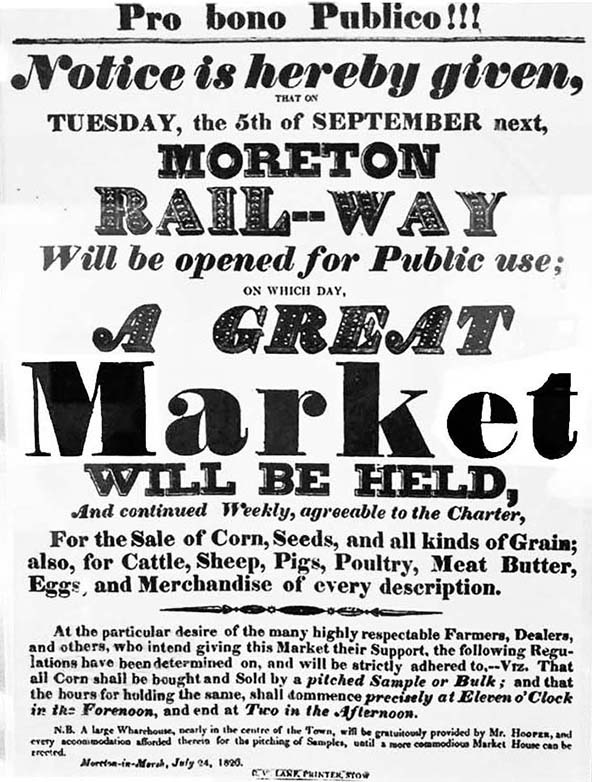

A hand drawn plan of Moreton-in-Marsh tramway wharf as it is thought to have looked in 1835. At this time the tramway only ran Moreton-in-Marsh to Stratford-upon-Avon as it was to be a further year before the [tramway] branch to Shipston-on-Stour opened. There are a number of very short sidings and this would have been for the operational convenience of the various wagon owners. Only one wagon turntable is present, in contrast to the wharf at Stratford-upon-Avon where they abounded. Whether the weighbridge was provided at the outset in 1826 is not known. Slightly curious is that the weighbridge was only directly accessible from certain sidings and it is likely these were predominantly used for coal and minerals traffic. The buildings, marked here only in outline, south side of the road were used by various merchants and also contained the headquarters of the Stratford & Moreton Railway Company. Today, the entrance from the High Street is the entrance to the supermarket now occupying the site.

A hand drawn plan of Moreton-in-Marsh tramway wharf as it is thought to have looked in 1835. At this time the tramway only ran Moreton-in-Marsh to Stratford-upon-Avon as it was to be a further year before the [tramway] branch to Shipston-on-Stour opened. There are a number of very short sidings and this would have been for the operational convenience of the various wagon owners. Only one wagon turntable is present, in contrast to the wharf at Stratford-upon-Avon where they abounded. Whether the weighbridge was provided at the outset in 1826 is not known. Slightly curious is that the weighbridge was only directly accessible from certain sidings and it is likely these were predominantly used for coal and minerals traffic. The buildings, marked here only in outline, south side of the road were used by various merchants and also contained the headquarters of the Stratford & Moreton Railway Company. Today, the entrance from the High Street is the entrance to the supermarket now occupying the site.

Construction

Construction of the Stratford and Moreton Railway was reported as being well underway in 1823. The rails were 12ft lengths of wrought iron fish belly rail mounted in iron chairs which themselves were spiked via wooden inserts in the stone block sleepers. Some 66,000 of these stone blocks were apparently ordered. The rails were 'T' shaped in cross section and mounted with the flat flange surface uppermost and upon which the wagon wheels ran. The running surfaces of the wheels were also therefore flat, in other words railheads and wheels were not profiled in the manner they are today. The underside of the rail flanges rested directly on top of the chairs the latter of which also served the same purpose as fishplates. The fish belly sections of the underside of the rails sat between the sleeper blocks. The whole was deeply ballasted to ease the passage of horses. As far as is known there was no form of cross ties at intervals to maintain the gauge and this arrangement was adequate for the slow speed horse-drawn wagons although there must have been some gauge spreading on curves.

The railway began at its station adjacent to the junction of the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal and River Avon. Stations on the railway, it should be mentioned, were referred to as ‘wharfs’, signifying the link with James and the canal system. That aside, this was also a time when railway terminology as we know it today was a long way from becoming more or less standardised. The track layout at the terminus was a little peculiar, at least to modern eyes, in that the sidings which sprang off to serve the basins (there were two basins) could only be accessed from the running line via a reversal. One of these sidings reached down to what is now the Royal Shakespeare Theatre but for what purpose is unknown. The original theatre on this site burned down in 1926.

Immediately after leaving the station/ wharf the line passed a toll house and then crossed the impressive bridge over the Avon. Both of these original features survive today. The railway then turned south and in later years would cross the Stratford-upon-Avon & Midland Junction Railway on a bridge at this point. The countryside south of Stratford-upon-Avon is of a rolling, if not exactly hilly, nature and construction involved some fairly considerable earthworks and gradients. There were a number of bridges, an abundance of level crossings and a tunnel where the line passed beneath the [Chipping] Campden Road about one mile north of Stretton-on-Fosse. Campden Road is now the B4035. Toll houses were provided at intervals (the reason for these is described in a later section). The route followed the Stour Valley through, from north to south, Atherstone-on-Stour, Preston-on-Stour, Alderminster and Ilmington at which point the Stour turned eastwards toward Shipston-on-Stour. The tramway then veered south south-west through Stretton-on-Fosse (named after the Fosse Way Exeter to Lincoln Roman road) towards Moreton-in-Marsh. This constituted the ‘main’ line of some 16 miles in length. On its approach to Moreton-in-Marsh the line crossed what is now Todenham Road by means of yet another level crossing after which the line turned sharply west south-west to arrive at its southern terminus known as ‘Moreton Wharf. Here were several buildings used as offices, stables, warehouses and domestic accommodation. The latter were rented to persons involved in the operation of the tramway or to those with businesses which transported their goods via the tramway or in a couple of cases rented to third parties

The OS 25 inch map surveyed in 1885 and published in 1887 shows the Campden Road Tunnel in situ and this would be the final OS map to do so. The track north and south of the tunnel is misaligned; probably this is merely a cartographic error for insofar as is known there was no 'dogleg' in the short tunnel and nor would there need to be. To the north can be seen Tunnel Wharf, one of several 'stations' positioned along the tramway. At some point in time a siding served a brickworks at Tunnel wharf as did another at Newbold Brickworks, to the south of Newbold Wharf. Some maps show these sidings, some do not depending upon period.

The OS 25 inch map surveyed in 1885 and published in 1887 shows the Campden Road Tunnel in situ and this would be the final OS map to do so. The track north and south of the tunnel is misaligned; probably this is merely a cartographic error for insofar as is known there was no 'dogleg' in the short tunnel and nor would there need to be. To the north can be seen Tunnel Wharf, one of several 'stations' positioned along the tramway. At some point in time a siding served a brickworks at Tunnel wharf as did another at Newbold Brickworks, to the south of Newbold Wharf. Some maps show these sidings, some do not depending upon period.

This plan is from an 1849 survey. It shows the possible maximum extent of the tramway sidings at Stratford-upon-Avon. Note the large number of wagon turntables, the track crossing the swing bridge over the cut between the two basins and the sidings serving what were predominantly coal wharfs on the left and alongside Waterside (named as such on the later map below). The location is the confluence of the Stratford Canal and River Avon, the canal coming in towards top left. Alongside coal, timber was another commodity catered for. The flow of these traffics was southbound, with northbound flows being predominantly agricultural produce, but there appears to have been no warehousing for this perhaps because produce was collected by traders immediately upon arrival, the maintaining of freshness being key. Click here for a large version.

This plan is from an 1849 survey. It shows the possible maximum extent of the tramway sidings at Stratford-upon-Avon. Note the large number of wagon turntables, the track crossing the swing bridge over the cut between the two basins and the sidings serving what were predominantly coal wharfs on the left and alongside Waterside (named as such on the later map below). The location is the confluence of the Stratford Canal and River Avon, the canal coming in towards top left. Alongside coal, timber was another commodity catered for. The flow of these traffics was southbound, with northbound flows being predominantly agricultural produce, but there appears to have been no warehousing for this perhaps because produce was collected by traders immediately upon arrival, the maintaining of freshness being key. Click here for a large version.

Several maps exist showing the tramway terminus at Stratford-upon-Avon, this one being the OS 6 inch map surveyed in 1885. The northern section of the tramway, it should be remembered, was never converted into a proper railway. By 1885 the fortunes of the northern section were declining and this map shows the by-then reduction in the number of sidings which had previously existed. Wagon turntables once proliferated and sidings had served the various coal wharfs which lined the east side of what had become Waterside. The tramway also once crossed the swing bridge over the cut between the two basins.

Several maps exist showing the tramway terminus at Stratford-upon-Avon, this one being the OS 6 inch map surveyed in 1885. The northern section of the tramway, it should be remembered, was never converted into a proper railway. By 1885 the fortunes of the northern section were declining and this map shows the by-then reduction in the number of sidings which had previously existed. Wagon turntables once proliferated and sidings had served the various coal wharfs which lined the east side of what had become Waterside. The tramway also once crossed the swing bridge over the cut between the two basins.

While railway construction in the 1820s was still something of a learning curve, mistakes were made which even for the time should have been apparent. These mistakes included cutting sides too steep, inadequate or no drainage and subsiding embankments. The steep cutting sides probably came about as steep sides meant narrow cutting width and therefore less land needed acquiring. If so it was a false economy as slippages were a problem throughout the life of the tramway. Jumping ahead for a moment to February 1828, a mere seventeen months after the tramway opened. A Benjamin Baylis who was a Stratford-upon-Avon coal merchant and a licensed user of the tramway (see the tramway in operation section) made a scathing complaint about the condition of the tramway. The actual document is quite lengthy so we will here give a summary of his complaints which were; stone sleeper blocks bedded directly upon natural earth; sleeper blocks sinking into soft clay; horses having to travel through a trench of mud in wet weather; sleeper blocks and rail chairs being imperfect and in some cases broken; sides of cuttings and embankments too upright; Potters Valley, Ditchford and other embankments slipping; fences and post railing in poor condition and in many cases broken. Mr Baylis clearly knew what he was talking about and his complaint also included remedies for all the various defects. The response from the Directors of the tramway was along the lines of and to use a modern phrase “If you can do any better .....” and that is precisely what happened. Thomas Oakley, who had supervised the line on behalf of John Rastrick, his employer, was dismissed and Baylis at his own suggestion took out a lease on the tramway at a rent of £2,100 per annum but with strings attached, among which were a requirement to maintain the line in good order. Oakley was replaced by a John Smith who oversaw the remedial work. Smith was an acquaintance of Baylis so it is possible Smith was appointed at the suggestion of Baylis. This all worked out well and the formerly loss making tramway began to return a profit. Given the list of defects and their remedies given by Baylis it might be assumed he had experience of railways or some other form of related engineering, such as earthworks, but no evidence has been found which supports this. Being a coal merchant perhaps he had some knowledge of colliery tramroads or of canal construction. Wherever or however he obtained his knowledge he was certainly a remarkable character for the time and it was perhaps unfortunate with hindsight that he did not oversee the construction of the tramway.

For a long time Britain lived in fear of and guarded against an invasion by the French, part of a desire by France to dominate Europe. Following the defeat of Napoleon at The Battle of Waterloo which formally ended with the Treaty of Paris on 20 November 1815, Britain and her allies went through a period of jubilation which came to an abrupt halt due to an economic downturn and the resultant high unemployment. This was the reason the branch of the tramway to Shipston-on-Stour was deferred. The time allowed for construction had elapsed and a new Act plus the raising of capital was therefore required. The Shipston-on-Stour branch finally opened on the 11th of February 1836, some ten years after the ‘main’ line and included the stations at Stretton-on-Fosse and Longdon Road. The line to Shipston-on-Stour branched off at Darlingscott Junction, sometimes referred to as Ilmington Junction, with points facing in the southbound direction. As a result, journeys between Moreton-in-Marsh and Shipston-on-Stour were not possible without a reversal. This would have been a nuisance with the horse drawn wagons but as Stratford-upon-Avon was the focal point of the tramway in respect of goods flows, the layout of the junction probably wasn't too serious an issue. The branch meandered its way eastwards and approached Shipston-on-Stour to the town's north west, it then turning sharply to the south for some 22 chains to enter the terminus. The hamlet of Darlingscott is thus spelled but the road leading to it from Shipston-on-Stour is spelled Darlingscote.

The reason for this seemingly peculiar routing lies in the plan for the tramway to turn northwards to a point north of Coventry where it would have tapped into the Hinckley Coalfield which in turn was connected to the Ashby Canal (Ashby-de-la-Zouch). Had this line been built in full, the line from Darlingscott Junction via Shipston would have been some 35 miles long. With the abandonment of the line beyond Shipston to the Hinckley Coalfield either of two scenarios then prevailed. Either Shipston would have been served by a branch heading south from a junction or the short southwards section into Shipston. The short southwards section into Shipston was built as an afterthought. If the latter was the case then Shipston would have been planned to have a station/ wharf outside of and to the north of the town. The route beyond Shipston is known to have been surveyed but that, it would appear, is as good as it got before the plan was abandoned.

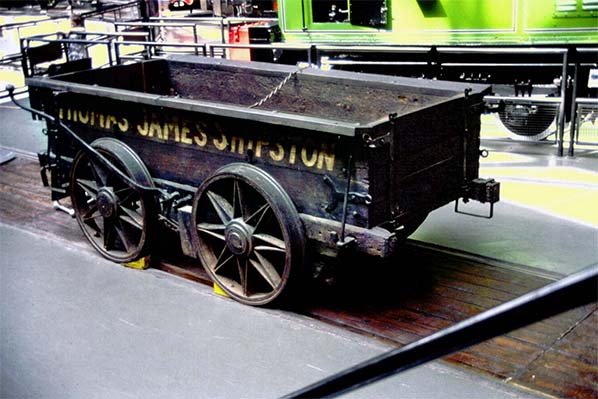

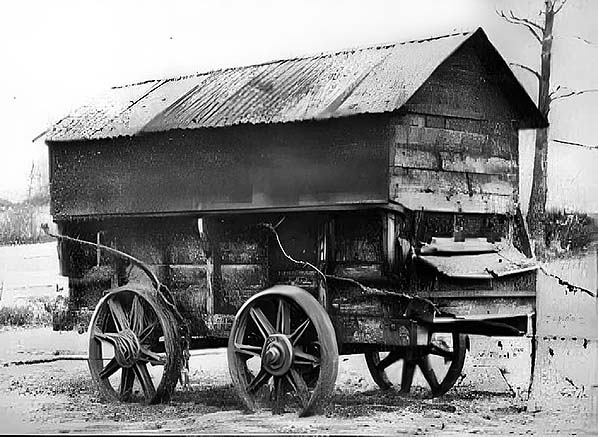

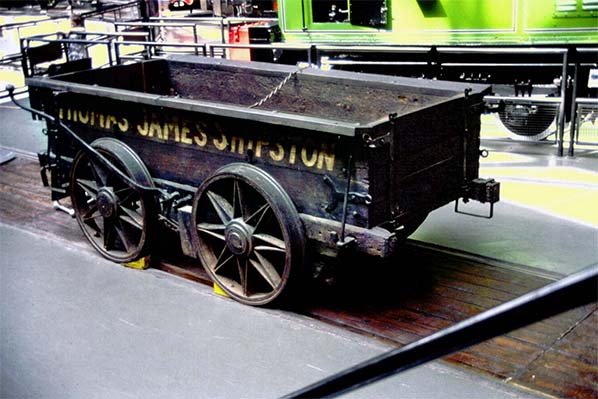

The preserved wagon at Stratford-upon-Avon, at the site of the wharf just north of the bridge over the River Avon. The wagon spent many years in use as a chicken coop on a farm at Alderminster before being rescued for preservation. While the wheel sets are genuine originals it is unclear if they are original to this particular wagon. The wheels are 3ft diameter and mounted upon 3½in diameter axles. Rescued for preservation in 1935 thanks to the efforts of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, the wagon stands upon a section of original track. It is thought the stone block sleepers lay where they were positioned in the 1820s but the rails and chairs were recovered from elsewhere. In 1935 much of the world, including Britain, was struggling through "The Great Depression" and nervousness about another World War was beginning to appear. It was also not very long after the northern section of the horse tramway had been abandoned and general interest in it would not have been particularly great. The rescue and preservation of this wagon was therefore quite an achievement. It is known that, when in service, these wagons carried the owner/operator's name and also a plate displaying his licence number. The Thomas Hutchings plate seen here was added subsequent to preservation; it is rather unkind to the eyes with words split between lines and perhaps did not look like this originally. During the 1980s an interpretation board was mounted midway along the body side. The wagon is today protected behind iron railings and has had the operator's details daubed right across the body side, including over the framing. This has probably been done for the benefit of tourists, making the wagon stand out more, but it is not particularly attractive (see photograph). The wagon, now at the National Railway Museum, is to a different design and while it also has the operator's name across the body sides it is not disfigured by external framework

The preserved wagon at Stratford-upon-Avon, at the site of the wharf just north of the bridge over the River Avon. The wagon spent many years in use as a chicken coop on a farm at Alderminster before being rescued for preservation. While the wheel sets are genuine originals it is unclear if they are original to this particular wagon. The wheels are 3ft diameter and mounted upon 3½in diameter axles. Rescued for preservation in 1935 thanks to the efforts of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, the wagon stands upon a section of original track. It is thought the stone block sleepers lay where they were positioned in the 1820s but the rails and chairs were recovered from elsewhere. In 1935 much of the world, including Britain, was struggling through "The Great Depression" and nervousness about another World War was beginning to appear. It was also not very long after the northern section of the horse tramway had been abandoned and general interest in it would not have been particularly great. The rescue and preservation of this wagon was therefore quite an achievement. It is known that, when in service, these wagons carried the owner/operator's name and also a plate displaying his licence number. The Thomas Hutchings plate seen here was added subsequent to preservation; it is rather unkind to the eyes with words split between lines and perhaps did not look like this originally. During the 1980s an interpretation board was mounted midway along the body side. The wagon is today protected behind iron railings and has had the operator's details daubed right across the body side, including over the framing. This has probably been done for the benefit of tourists, making the wagon stand out more, but it is not particularly attractive (see photograph). The wagon, now at the National Railway Museum, is to a different design and while it also has the operator's name across the body sides it is not disfigured by external framework

Copyright photo by John Alsop collection

Wagons

All wagons with the exception of Rastrick's somewhat mysterious one-off described earlier resembled the typical English farm cart of the time with the obvious exception of the running gear, which was manufactured by Messrs. Smith & Willey at their Windsor Foundry, Smithdown Road in Liverpool. It seems likely that Smith & Willey manufactured the running gear for all the wagons. Bodywork was of sturdy wooden construction with longitudinal frame members projecting slightly beyond each end to form simple dumb buffers. There was a brake operating on one wheel and manually worked by means of a long lever. This mechanism was duplicated on both sides of the wagons but diagonally opposite to allow the driver to operate from either end. Horses were attached via the usual tack to a chain attached to the wagons by wrought iron brackets, two at each end of the wagons. Wagons could be coupled by a simple chain and hook arrangement. The equipment supplied by Smith & Willey would have been delivered by waterway to Stratford-on-Avon and it is likely that wagon bodywork was manufactured by local carpenters. Surviving wagons display variations in the body design but whether these variations were original or subsequent modifications or rebodying is not known. On the tramway the wagons were restricted to a maximum weight of 4 tons laden. A horse in good fettle was reckoned to be capable of hauling 8 tons on rails, meaning a maximum of two fully laden wagons. Maximum permitted speed on the tramway was 8 MPH but quite how this was policed, if at all, and for how long horses could maintain this speed, if they could, is not known.

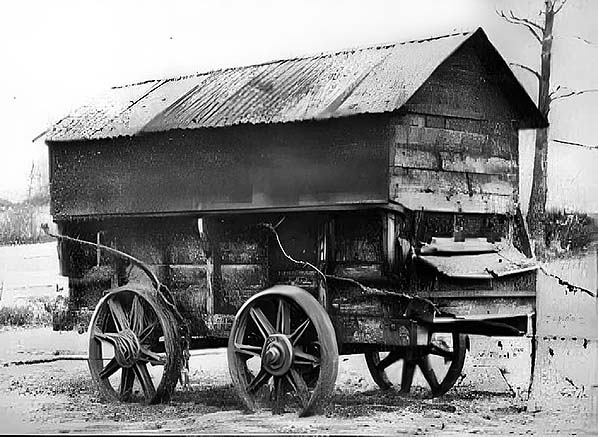

The tramway wagon now preserved at Stratford-upon-Avon seen here when in use as a chicken coop on a farm sometime between the wars. The location of the farm is thought to have been Alderminster although sources vary between there, Newbold-on-Stour and Ilmington. All three places are close to each other so the farm could have been somewhere in between. There is some damage to the photograph, especially around the wheels and hubs of the wagon but this does not detract from the historical record. Chicken coops should ideally be able to be moved around and indeed most are wheeled to permit this, but this wagon's wheels appear to be sinking into the ground so presumably mobility was not a requirement in this case. The wagon is largely intact although the leather-faced wooden brake block is missing. There was a brake lever on both sides and diagonally opposite each other but it is unclear if the other lever was present when on the farm. Close examination shows the presence of a plate on the bodyside, behind and just above the wheel nearest the camera. This would have been the plate giving details of the wagon's operator's licence when in use on the tramway. Under magnification some letters can be made out but the whole is totally indeterminable. One wonders what became of this plate as it is no longer present. The other preserved wagon, in the care of the National Railway Museum, is said to have had a similar history and it is quite possible these were not the only wagons to have ended up on farms.

The tramway wagon now preserved at Stratford-upon-Avon seen here when in use as a chicken coop on a farm sometime between the wars. The location of the farm is thought to have been Alderminster although sources vary between there, Newbold-on-Stour and Ilmington. All three places are close to each other so the farm could have been somewhere in between. There is some damage to the photograph, especially around the wheels and hubs of the wagon but this does not detract from the historical record. Chicken coops should ideally be able to be moved around and indeed most are wheeled to permit this, but this wagon's wheels appear to be sinking into the ground so presumably mobility was not a requirement in this case. The wagon is largely intact although the leather-faced wooden brake block is missing. There was a brake lever on both sides and diagonally opposite each other but it is unclear if the other lever was present when on the farm. Close examination shows the presence of a plate on the bodyside, behind and just above the wheel nearest the camera. This would have been the plate giving details of the wagon's operator's licence when in use on the tramway. Under magnification some letters can be made out but the whole is totally indeterminable. One wonders what became of this plate as it is no longer present. The other preserved wagon, in the care of the National Railway Museum, is said to have had a similar history and it is quite possible these were not the only wagons to have ended up on farms.

Images above and below. Two of the surviving horse-drawn tramway wagons are on public display. Above, looking a little incongruous at the National Railway Museum, York but nevertheless safely preserved is this example. Wagons were owner-operated under licence, a condition of which was the owner's name being displayed. Wagons were also required to carry a number, not present on either of these two wagons, which was probably the owner's licence number as opposed to a fleet number. Thomas James was a coal merchant based at Shipston-upon-Stour. This wagon is usually dated to circa 1840 and was photographed at York on 18 June 1999. Below, this wagon is on display in the open air at Cox's Yard, Stratford-upon-Avon, just north of the tramway bridge over the Avon. It stands upon an original length of track which is useful as it provides a 'real time' idea of what the fish belly rails on stone block sleepers looked like. This wagon had famously spent many years in use as a chicken coop before being preserved. Newbold Limeworks was located on the northern section of the tramway between Darlingscott just north of Newbold Wharf. The name on this wagon will of course have been applied when or after the wagon was preserved but whether the name was originally daubed in such an untidy manner over the external body framework is not known. Comparison of these wagons reveals a number of differences but whether both survive in as-built condition, not withstanding repairs and conservation work, is unknown

Images above and below. Two of the surviving horse-drawn tramway wagons are on public display. Above, looking a little incongruous at the National Railway Museum, York but nevertheless safely preserved is this example. Wagons were owner-operated under licence, a condition of which was the owner's name being displayed. Wagons were also required to carry a number, not present on either of these two wagons, which was probably the owner's licence number as opposed to a fleet number. Thomas James was a coal merchant based at Shipston-upon-Stour. This wagon is usually dated to circa 1840 and was photographed at York on 18 June 1999. Below, this wagon is on display in the open air at Cox's Yard, Stratford-upon-Avon, just north of the tramway bridge over the Avon. It stands upon an original length of track which is useful as it provides a 'real time' idea of what the fish belly rails on stone block sleepers looked like. This wagon had famously spent many years in use as a chicken coop before being preserved. Newbold Limeworks was located on the northern section of the tramway between Darlingscott just north of Newbold Wharf. The name on this wagon will of course have been applied when or after the wagon was preserved but whether the name was originally daubed in such an untidy manner over the external body framework is not known. Comparison of these wagons reveals a number of differences but whether both survive in as-built condition, not withstanding repairs and conservation work, is unknown

Photo by Cambooxer reproduced from Wikipedia under creative commons licence

Photo by Len Williams. Reproduced from Geograph under creative commons licence

Photo by Len Williams. Reproduced from Geograph under creative commons licence

Operation of the tramway

As previously mentioned, wagons were owner-operated as were the horses and in some cases under licence from the company. ‘in some cases’ means that unlicensed operators were required to defer to licensed operators who had priority but were required to travel at 8 MPH, the speed limit mentioned in an earlier section. The licence cost was one shilling. The tramway was of course single track and wagons travelled in both directions. To cater for this what are usually described as ‘turnouts’ were provided at approximate quarter mile intervals and midway between turnouts was a sign displaying the letter ‘D’. What ‘D’ stood for is unconfirmed but was probably ‘Defer’ or perhaps ‘Deviate’. When two wagons were approaching each other in opposite directions, whichever wagon was last to pass the ‘D’ sign was required to set back onto the nearest turnout to allow the other wagon to pass. There was a rule which stated wagons were to pass on the left which implies turnouts were provided on both sides of the track, one for each direction. What form these turnouts took is unclear and while some sources have referred to loops, it seems likely they were merely short single ended sidings which would be more likely, as a loop would be of no use for a wagon required to set back, only to then carry on in the same direction it was previously travelling. Maps showing the tramway with track in situ exist but none have been discovered which show these turnouts.

There were mileposts at quarter mile intervals, used to calculate tolls. Toll houses were located at intervals as were some form of weighbridges, details being written on wagons to indicate distance travelled, loads and tolls paid with these details being noted at the following tollhouse and so on. This system was not far removed from that of the turnpike roads and may well have been based upon it. With the need for wagons to comply with the ‘D’ rule as well as stopping at tollhouses a journey on the tramway must have been quite a performance. On the plus side far easier passage would have been possible in comparison with the roads of the time.

There were accidents on the tramway including fatal to both men and horses. The usual causes were out of control wagons on the gradients (the steepest was 1:53, on the Shipston branch) and horses falling only to be run over by the wagons which when laden must have been difficult to stop with the crude braking system if they became out of control. We know details of accidents through surviving records as published mainly in newspapers and there were probably others, especially the non-fatal, which either went unrecorded or were but the records are lost. All in all though, the tramway seems to have operated without serious accidents occurring too frequently. Supposedly on falling gradients horses were unhitched and coaxed up onto the wagons which then trundled down the gradients by gravity. While this practice was common on early railways and tramways/ tramroads a special wagon, or simply an empty wagon, was often provided for this purpose but it is not known if this was the case on the Stratford and Moreton. If it was not, a somewhat comical vision of a horse perched on a loaded wagon is conjured up.

Springfield Cutting about one mile south of Stratford-upon-Avon facing north towards Stratford. This section of the tramway was not converted into a railway and most sources agree that the last wagon trundled along this section in about 1904 and this view would have been taken soon afterwards. Nature is gradually taking over the track and the rails were lifted by or during 1918. This bridge has survived.

Springfield Cutting about one mile south of Stratford-upon-Avon facing north towards Stratford. This section of the tramway was not converted into a railway and most sources agree that the last wagon trundled along this section in about 1904 and this view would have been taken soon afterwards. Nature is gradually taking over the track and the rails were lifted by or during 1918. This bridge has survived.

Copyright photo by John Alsop collection

The surviving, Grade II listed bridge over Springfield Cutting seen here in 2004. The camera is facing north-west and the location is immediately adjacent to the Shipston Road, currently the A3400. When driving along this road the bridge is not immediately obvious and is a 'blink and you'll miss it' situation especially during the summer when foliage is abundant. The bridge carries a private road to Springfield House and currently, 2024, a roadside sign to that effect is the marker to look out for. While the bridge arch appears quite sturdy, one wonders what damage tree roots are causing or will cause in the future. Photo from Historic England

The surviving, Grade II listed bridge over Springfield Cutting seen here in 2004. The camera is facing north-west and the location is immediately adjacent to the Shipston Road, currently the A3400. When driving along this road the bridge is not immediately obvious and is a 'blink and you'll miss it' situation especially during the summer when foliage is abundant. The bridge carries a private road to Springfield House and currently, 2024, a roadside sign to that effect is the marker to look out for. While the bridge arch appears quite sturdy, one wonders what damage tree roots are causing or will cause in the future. Photo from Historic England

While we do not know for certain when passengers were first carried, it was probably from the outset in 1826 and unofficially. These passengers would have simply sat on the wagons, on top of a load of coal or other goods. While often somewhat whimsical, watercolours and drawings depicting this practice on several early railways are quite common. The suggestion that passengers were carried from the outset may be borne out by the introduction of licenses for the carriage of passengers on 12 December 1834, thereby making it official. The licence system was by no means simple, probably to cater for the various requirements of licence holders. Licence fees were 2/- (two shillings) for one day regardless of which section of the tramway the licence holder wished to operate over. Weekly fees varied from 4/6d to 6/- while monthly fees were either 15/- or £1. Licence holders were issued with a plate to be attached to their wagons, presumably displaying the licence number.

For licensing purposes the tramway was divided into sections as follows:

- From Stratford to Ilmington Wharf, Moreton or Shipston or any place in between

- From Moreton and as above

- From Shipston and as above

In all cases the licence covered return journeys between the points mentioned. It is curious that Shipston-on-Stour was included as in 1834 this branch was still two years away from opening. The probable reason for the inclusion may have simply been anticipation of the branch opening. ‘Any place in between’ suggests passengers could be picked up and set down wherever they could access the tramway, which in the majority of cases would have been road crossings. The northern section of the tramway largely ran alongside what is now the A3400 road and passed right through the middle of the village of Alderminster, some five miles from Stratford-upon-Avon. No doubt Alderminster was one of those ‘any place in between’ points at which passengers were picked up and set down.

The flat crossing mystery

Construction of the Oxford, Worcester & Wolverhampton Railway (OW&WR) proceeded from the Evesham direction and its station at Moreton-in-Marsh opened on 4 June 1853. At Wolvercot Junction (sometimes spelled 'Wolvercote') just north of Oxford, the line junctioned with the broad gauge Oxford & Rugby Railway. The Oxford & Rugby was never to reach Rugby and reached only as far as Banbury. The OW&WR was originally single track and therefore Moreton-in-Marsh had a single platform on the down, west, side of the line. The railway was supported by the Great Western Railway and by Act the OW&WR was required to cater for the Great Western's broad gauge, but what actually happened is not exactly crystal clear. The consensus among authors is that a single track mixed gauge line was constructed and a second track was added soon afterwards, together with a second platform added at Moreton-in-Marsh. At this time there was [another] economic downturn, caused in no small part by crop failures, and the Great Western seemingly lost interest in the OW&WR who noticed the Great Western was concentrating its resources on its route via Banbury and Leamington Spa. Given the economic situation of the time this was not unreasonable but the OW&WR felt compelled to ask the London & North Western Railway to operate trains on its behalf. The OW&WR was reputedly built as a competitor to the London & Birmingham Railway which at the time had a less than good reputation, although how such a circuitous route could hope to compete with the London & Birmingham is puzzling but such as it was during the so-called Railway Mania.

Relations with the Great Western eventually eased and reputedly only one broad gauge train ever traversed the OW&WR, on 13 April 1854, probably a special for officers and invited guests, with public passenger services only ever operated by standard gauge trains. A legacy of what might be called ‘the broad gauge which never was’, is the wide track spacing in the Moreton-in-Marsh area. In any event, by this time the broad gauge was being abandoned and on 31 March 1869 the last broad gauge train north of Oxford ran on, of course, the Banbury line.

The Stratford and Moreton Railway approached its Moreton Wharf terminus in a west south-westerly direction on the east side of what would become the course of the OW&WR while the actual terminus was on what would become the west side of the OW&WR. It is well reported that construction of the OW&WR severed the tramway at the eastern end of its Moreton Wharf terminus. It is what happened next which is a unclear and there are a number of opinions including a flat crossing and the more logical suggestion that the tramway was simply diverted southwards to terminate on the ‘Up’ side of the OW&WR as indeed was the situation in subsequent years. The map reproduced below suggests otherwise.

This is an extract from the 1855 (published date) 1:1800000 map which appears to show the tramway crossing the OW&WR to enter its original Moreton Wharf terminus. However, maps of this scale cannot show the finer details as witnessed by the branch from Honeybourne appearing to junction with the tramway just south of Stratford-upon-Avon which was most certainly not the case. The vagueness due to map scale notwithstanding, the suggestion of the tramway crossing the OW&WR is intriguing. The truth would be found on a one or six inch map which was surveyed, as opposed to published, at the time the OW&WR railway was built through Moreton-in-Marsh but none are known to exist. What we can be sure of is that the tramway was diverted, as mentioned, southwards at some point in time although no evidence has been found that at least some of the tramway facilities at Moreton Wharf were replaced on the Up side of the OW&WR. One further possibility is that a flat crossing was installed when the OW&WR was single track, being abandoned and the tramway diverted when the former was double tracked. In August 1857 Mr. Sherriff, General Manager of the OW&WR, wished to inspect the line with a view to introducing 'proper' passenger carriages. Accordingly a steam locomotive, with carriage, reached Shipston-upon-Stour and a report in The Worcester Herald of 5 September 1857 confirms this did indeed take place. Certainly, therefore, the tramway was connected to the OW&WR at Moreton-in-Marsh by August 1857. The outcome seems to have been the trial with a locomotive being deemed successful and probably because of the rather flimsy track.

This is an extract from the 1855 (published date) 1:1800000 map which appears to show the tramway crossing the OW&WR to enter its original Moreton Wharf terminus. However, maps of this scale cannot show the finer details as witnessed by the branch from Honeybourne appearing to junction with the tramway just south of Stratford-upon-Avon which was most certainly not the case. The vagueness due to map scale notwithstanding, the suggestion of the tramway crossing the OW&WR is intriguing. The truth would be found on a one or six inch map which was surveyed, as opposed to published, at the time the OW&WR railway was built through Moreton-in-Marsh but none are known to exist. What we can be sure of is that the tramway was diverted, as mentioned, southwards at some point in time although no evidence has been found that at least some of the tramway facilities at Moreton Wharf were replaced on the Up side of the OW&WR. One further possibility is that a flat crossing was installed when the OW&WR was single track, being abandoned and the tramway diverted when the former was double tracked. In August 1857 Mr. Sherriff, General Manager of the OW&WR, wished to inspect the line with a view to introducing 'proper' passenger carriages. Accordingly a steam locomotive, with carriage, reached Shipston-upon-Stour and a report in The Worcester Herald of 5 September 1857 confirms this did indeed take place. Certainly, therefore, the tramway was connected to the OW&WR at Moreton-in-Marsh by August 1857. The outcome seems to have been the trial with a locomotive being deemed successful and probably because of the rather flimsy track.

The result of the OW&WR arriving at Moreton-in-Marsh resulted in the railway company taking over the tramway on a perpetual lease. At the time the tramway was turning a profit and the OW&WR railway left the tramway to carry on as previously. This included leaving officers of the tramway in their posts for a time but they were later dismissed as a cost saving measure. In 1853 the OW&WR railway instigated some remedial work to halt, or try to halt, slippages, improved drainage and possibly some track re-laying using conventional transverse sleepers. In the case of the latter however, photographs of the all-but-derelict northern section of the tramway taken in the early 20th century show no evidence of this although track re-laying in the manner described may have been confined to the Shipston-on-Stour section. Some validity to the latter theory might be provided by the opening by the OW&WR of its branch from Honeybourne to Stratford-upon-Avon which although not opening until 12 July 1859 had been authorised by Act as early as 1846. This line eventually became part of the Stratford - Cheltenham line. It was the Honeybourne - Stratford-upon-Avon line which sounded the death knell for the northern section of the tramway although this section did manage to plod on with increasingly infrequent use into the early 20th century.

Campden Road Tunnel was to be opened out in 1887-8 and a new bridge provided for the road to cross the resulting cutting. A further brickworks was served just outside Moreton-in-Marsh but for space reasons is not shown on this diagram. Newbold Limekilns later became a brickworks site. The intermediate locations north of Darlingscott Junction are included to give a geographical context and are not necessarily the locations of official stopping places, i.e. wharfs.

Campden Road Tunnel was to be opened out in 1887-8 and a new bridge provided for the road to cross the resulting cutting. A further brickworks was served just outside Moreton-in-Marsh but for space reasons is not shown on this diagram. Newbold Limekilns later became a brickworks site. The intermediate locations north of Darlingscott Junction are included to give a geographical context and are not necessarily the locations of official stopping places, i.e. wharfs.

Mr Bull's passenger service

Mr Bull of The George Hotel, Shipston-upon-Stour was given a licence by the OW&WR to operate a passenger service, which commenced on the 1st of August 1853, but using a proper railway carriage of which some details are known. It was a diminutive three-compartment vehicle, two Second Class and one First Class, modified for horse haulage. There was an external seat for the driver mounted on each end. To imagine what this vehicle looked like one only has to think of the well known, yellow, Liverpool & Manchester Railway carriages but with the accoutrements for horse haulage added at each end. A parallel might be the Port Carlisle ‘Dandy’ although this was purpose built for horse haulage and its body was to a different design. Mr Bull's service also catered for Third Class passengers and these, like on the ‘Dandy’, would have been accommodated on the external seat with the driver. This would have been most unpleasant during winter or rough weather but people were hardier in those days; they had to be, and in any case it was far better than having to perch atop a coal wagon. Through tickets were available to Oxford, London and probably other places.

The timetable below dates from August 1858 and Mr Bull's service disappeared from timetables in September 1858. The following month the OW&WR advertised for a replacement operator but it appears none was forthcoming, therefore this particular passenger service never ran again. Why Mr Bull ceased to operate the service is not known. The fact the OW&WR sought another operator may suggest Mr Bull operated the service single-handedly. However The Railway Magazine of February 1935 offered a minor contradiction by stating “This ceased when the branch from Honeybourne to Stratford was opened on July 11, 1859”. It is well recorded that the Honeybourne - Stratford line sounded the death knell for the northern section of the tramway but this fails to answer one question; If Mr Bull ceased his passenger service for the aforementioned reason then why did the OW&WR seek a new operator when the operation can be assumed to have become unremunerative? On the other hand, perhaps this is why no new operator came forward. As an aside it will be noted there is a date conflict regarding the opening of the Honeybourne - Stratford line, July the 11th 1859 and July the 12th 1859. Perhaps the 11th of July was the official opening day and public services commenced the following day. Whatever the answer, the difference of one day has no relevance to Mr Bull's tramway passenger service.

Pages 104 (left) and 105 (right) of the 1858 Bradshaw which have unfortunately received some damage. The times for Mr Bull's horse-drawn service are shown. The timetables imply the service ran only between Stratford-on-Avon and Shipston-on-Stour but it also ran to Moreton-in-Marsh although the timetable gives only the times of connecting trains at the latter. As far as is known Mr Bull operated only one carriage, therefore a reversal involving the running-round of the horse would have been necessary at Darlingscott Junction. Click here for a large version.

Pages 104 (left) and 105 (right) of the 1858 Bradshaw which have unfortunately received some damage. The times for Mr Bull's horse-drawn service are shown. The timetables imply the service ran only between Stratford-on-Avon and Shipston-on-Stour but it also ran to Moreton-in-Marsh although the timetable gives only the times of connecting trains at the latter. As far as is known Mr Bull operated only one carriage, therefore a reversal involving the running-round of the horse would have been necessary at Darlingscott Junction. Click here for a large version.

Given that Mr Bull operated a conventional, for the time, carriage it is not unreasonable to wonder if some form of platform was provided at Stratford and Shipston. If so they would likely have been crude wooden affairs or simply earth mounds but no evidence of any such has been found. Railway carriages of that era had either footboards running the length of the body or steps accessing individual compartments from ground level. In the absence of any evidence of platforms, passengers using Mr Bull's service probably merely clambered up and down from and to ground level.

The Great Western Railway takeover

The OW&WR merged with a number of other companies with effect from the 1st of July 1860 and as a result changed its name to the ‘West Midland Railway’. This was merely a geographically suitable title and had no connection with the county now known as West Midlands which was not created until 1974. The West Midland Railway was vested into the Great Western Railway on the 1st of August 1863 and finally legally ceased to exist under the Great Western Railway Act, 1872. This of course meant the Great Western found itself owner of the Stratford & Moreton Tramway and while one might think the Great Western would want to get rid, this was not the case and the company left the tramway to plod on with horse traction much as before.

Movements of people and goods to and from Shipston-on-Stour had always focussed upon Stratford-on-Avon rather than Moreton-in-Marsh and despite the latter eventually having a main line railway connection. An attempt had been made to close the Shipston branch in 1862 but this met with much hostility and calls for better railway facilities to serve the town. By this time horse-drawn tramways and railways had become very outmoded, although a small number carried on into the 20th century including the northern section of the Stratford and Moreton. During the 1870s the Great Western came under fire due to its charges for use of the tramway. This resulted in the appearance of a competitor in 1880 with the rather long-winded title, The Shipston-on-Stour Steam Locomotive and Coal Company Limited. This outfit had two locomotives, insofar as is known, of which one was an Aveling & Porter contraption. However, this was a road operation and it quickly found itself embroiled in a number of legal matters including highway obstruction, damage to road surfaces and locomotives not consuming their own smoke. This was a form of what we would today call a ‘Road Train’ and lasted just two years. By this time traffic was in any case tailing-off considerably on the tramway and seemingly regardless of the GWR's charges so quite what the road outfit hoped to achieve is hard to understand. The requirement for locomotives to ‘consume their own smoke’ was to rear its ugly head again when the GWR planned to convert the tramway to locomotive operation by which time it was archaic and outdated. The requirement was written into Acts from the very early days of steam traction be they on rail or road. It was probably the reason why early steam locomotives often burned coke rather than coal.

A surviving and well maintained former tramway bridge in the southern outskirts of Stratford-upon-Avon. The tramway passed over the bridge left to right and this view faces east from the playing fields towards Shipston Road, the bridge being opposite No. 92.

Photo by David Stowell. Reproduced from Geograph under creative commons licence

The original Act of 1833 had stipulated, among many things, that if locomotives were to be used on the tramway, all road crossings had to be by means of bridges. When the Great Western decided to build, i.e. upgrade the Shipston-on-Stour branch from a tramway, the 1833 Act had to be revoked by The Great Western Railway No.1 Act of 1884 which latter continued to include the ‘smoke consumption’ clause but “so far as practicable” which for all intents and purposes meant the clause could be ignored within reason. The Act of 1884 included further stipulations which meant that although the Shipston-on-Stour branch, as rebuilt by the Great Western, was not a Light Railway it was in effect operated as though it was. For example a speed limit of 20 MPH was imposed with 4 MPH at road crossings even though road crossings were, for a time anyway, provided with crossing keepers. The conversion of the Moreton - Shipston section to a proper railway also involved the opening out of Campden Road Tunnel.

With the opening of the Shipston-on-Stour branch in 1889, which included a new south-to-east chord avoiding Darlingscott Junction, the horse tramway was disconnected at the point where the new chord turned away eastwards to the north of Stretton-on-Fosse. The tramway continued to operate, infrequently, between Longdon Road where transshipment facilities were provided and Stratford-upon-Avon. The remaining section then came to be known, officially or otherwise, as the Stratford-on-Avon and Longdon Road Tramway.

For an interesting description of the abandoned tramway explored in 1997 see David Shaws blog The Stratford & Moreton Tramway. It should be remembered that with the passage of time parts of the description may have changed, for example at Todenham Road level crossing

Sources and further reading:

- The Stratford & Moreton Tramway, John Norris, Railway and Canal Historical Society 1987 ISBN 0 901461 40 7

- The Shipston-on-Stour Branch, Jenkins/Carpenter, Wild Swan Publications Ltd. 1997 ISBN 1 874103 34 8

- Hand-Book of Stations, British Transport Commission Railway Clearing House 1956

- Clinker's Register of Closed Passenger Stations and Goods Depots, C. R. Clinker, Avon Anglia 1978 ISBN 0 905466 19 5

- Railway Passenger Stations in Great Britain, Michael Quick, Fifth Edition Version 5.05 September 2023. This is an online edition available via the Railway and Canal Historical Society.

-

-

- Old Maps Online

- David Rumsey Map Collection

- Warwickshire Railways

-

- The National Archives

- National Railway Museum

-

David Shaw's blog -

The Stratford & Moreton Tramway

In addition, various timetables have been used or consulted either from the author's own collection or from Timetable World.

For further reading it is recommended the books listed above by Norris and Jenkins/ Carpenter are both acquired. The latter has a section on the horse tramway and both books contain information which the other does not, thereby complimenting each other. The Warwickshire Railways website has a comprehensive collection of tramway photographs dating from and subsequent to the time when the tramway was in effect derelict.

Proof reading Alan Lawrence

A painting by artist

A painting by artist  The surviving tramway bridge over the Avon at Stratford-upon-Avon, seen here in 2010. This view is facing north-west towards the terminus wharf where the preserved wagon is located. The house at the far end of the bridge was originally a toll house; this is how revenue was collected, it being payable by the operators of the horse-drawn wagons.

The surviving tramway bridge over the Avon at Stratford-upon-Avon, seen here in 2010. This view is facing north-west towards the terminus wharf where the preserved wagon is located. The house at the far end of the bridge was originally a toll house; this is how revenue was collected, it being payable by the operators of the horse-drawn wagons.

A hand drawn plan of Moreton-in-Marsh tramway wharf as it is thought to have looked in 1835. At this time the tramway only ran Moreton-in-Marsh to Stratford-upon-Avon as it was to be a further year before the [tramway] branch to Shipston-on-Stour opened. There are a number of very short sidings and this would have been for the operational convenience of the various wagon owners. Only one wagon turntable is present, in contrast to the wharf at Stratford-upon-Avon where they abounded. Whether the weighbridge was provided at the outset in 1826 is not known. Slightly curious is that the weighbridge was only directly accessible from certain sidings and it is likely these were predominantly used for coal and minerals traffic. The buildings, marked here only in outline, south side of the road were used by various merchants and also contained the headquarters of the Stratford & Moreton Railway Company. Today, the entrance from the High Street is the entrance to the supermarket now occupying the site.

A hand drawn plan of Moreton-in-Marsh tramway wharf as it is thought to have looked in 1835. At this time the tramway only ran Moreton-in-Marsh to Stratford-upon-Avon as it was to be a further year before the [tramway] branch to Shipston-on-Stour opened. There are a number of very short sidings and this would have been for the operational convenience of the various wagon owners. Only one wagon turntable is present, in contrast to the wharf at Stratford-upon-Avon where they abounded. Whether the weighbridge was provided at the outset in 1826 is not known. Slightly curious is that the weighbridge was only directly accessible from certain sidings and it is likely these were predominantly used for coal and minerals traffic. The buildings, marked here only in outline, south side of the road were used by various merchants and also contained the headquarters of the Stratford & Moreton Railway Company. Today, the entrance from the High Street is the entrance to the supermarket now occupying the site. The OS 25 inch map surveyed in 1885 and published in 1887 shows the Campden Road Tunnel in situ and this would be the final OS map to do so. The track north and south of the tunnel is misaligned; probably this is merely a cartographic error for insofar as is known there was no 'dogleg' in the short tunnel and nor would there need to be. To the north can be seen Tunnel Wharf, one of several 'stations' positioned along the tramway. At some point in time a siding served a brickworks at Tunnel wharf as did another at Newbold Brickworks, to the south of Newbold Wharf. Some maps show these sidings, some do not depending upon period.

The OS 25 inch map surveyed in 1885 and published in 1887 shows the Campden Road Tunnel in situ and this would be the final OS map to do so. The track north and south of the tunnel is misaligned; probably this is merely a cartographic error for insofar as is known there was no 'dogleg' in the short tunnel and nor would there need to be. To the north can be seen Tunnel Wharf, one of several 'stations' positioned along the tramway. At some point in time a siding served a brickworks at Tunnel wharf as did another at Newbold Brickworks, to the south of Newbold Wharf. Some maps show these sidings, some do not depending upon period. This plan is from an 1849 survey. It shows the possible maximum extent of the tramway sidings at Stratford-upon-Avon. Note the large number of wagon turntables, the track crossing the swing bridge over the cut between the two basins and the sidings serving what were predominantly coal wharfs on the left and alongside Waterside (named as such on the later map below). The location is the confluence of the Stratford Canal and River Avon, the canal coming in towards top left. Alongside coal, timber was another commodity catered for. The flow of these traffics was southbound, with northbound flows being predominantly agricultural produce, but there appears to have been no warehousing for this perhaps because produce was collected by traders immediately upon arrival, the maintaining of freshness being key. Click

This plan is from an 1849 survey. It shows the possible maximum extent of the tramway sidings at Stratford-upon-Avon. Note the large number of wagon turntables, the track crossing the swing bridge over the cut between the two basins and the sidings serving what were predominantly coal wharfs on the left and alongside Waterside (named as such on the later map below). The location is the confluence of the Stratford Canal and River Avon, the canal coming in towards top left. Alongside coal, timber was another commodity catered for. The flow of these traffics was southbound, with northbound flows being predominantly agricultural produce, but there appears to have been no warehousing for this perhaps because produce was collected by traders immediately upon arrival, the maintaining of freshness being key. Click  Several maps exist showing the tramway terminus at Stratford-upon-Avon, this one being the OS 6 inch map surveyed in 1885. The northern section of the tramway, it should be remembered, was never converted into a proper railway. By 1885 the fortunes of the northern section were declining and this map shows the by-then reduction in the number of sidings which had previously existed. Wagon turntables once proliferated and sidings had served the various coal wharfs which lined the east side of what had become Waterside. The tramway also once crossed the swing bridge over the cut between the two basins.