Notes: When the single-track line opened between Cambridge and the junction with the Newmarket & Chesterford line, one mile west of Six Mile Bottom station, on 9 October 1851, Fulbourn station was not ready. It probably did not open with the line and did not appear in Bradshaw until August 1852.

It had a very similar building to the other new intermediate station at Cherry Hinton and was sited on the west side of Hay Street (renamed Station Road in the twentieth century). The station was provided with a two-storey brick station house beneath a pitched slate roof with two single-storey wings, one at the rear and the other facing onto the platform at the west end. A ticket window, protected by a porch in later years, was located in the end wall of the building facing onto Hay Street. The doorway at the front of the building decorated with plain pilasters and a pediment opened onto a short low platform. This feature was found on many Newmarket & Chesterford buildings, including crossing keepers' cottages. In the early years trains only ever stopped at Fulbourn station by request.

The Eastern Counties Railway timetable and map of 1853 shows the spelling of the station as Fulbourn (which is the accepted spelling of the village) and the February 1863 Bradshaw also shows that spelling but by the twentieth century the station had become Fulbourne, and this incorrect spelling appeared in all timetables and on tickets and station signs until closure.

With the coming of the railway, a community built up around the station. The ‘Railway Tavern’ opened to the south of the station in 1858. It survived into the 1960s but with declining rail traffic it was forced to close. It was bought by local farmer John Lacey and two years later, in 1966, the building was demolished. A steam mill had opened to the north of the station by 1863. It worked into the 1930s and finally closed in 1963.

Doubling of the track was first mooted in late 1874; this included ‘single line alterations, additional sidings, signals and platforms’ at a number of stations on the GER system. Curiously, the cost for the changes at Fulbourne was stated as being £4,085 - roughly twice the cost of alterations elsewhere. However, a further entry, in the GER company records for Dec 1874, gives the aforementioned £4085 as being the cost of ‘line doubling of the Fulbourne Branch’.

In October 1874, plans were discussed for a ‘passing place’ at Fulbourne and in June 1875, signalling works at Fulbourne were agreed at a cost of £579; Saxby & Farmer were the contractors. A signal box with an 18-lever frame was built at the west end of the stationmaster’s house in 1885. Fulbourne was a fine example of one of the earliest standard signal boxes of the Great Eastern Railway. Although first seen in the 1860s, standard contractors’ designs were the norm until 1873. The box controlled access to the goods yard but the level crossing gates were always hand-operated.

With the doubling of the line the station was re-sited to the east side of Hay Road. The new station had two facing platforms, the up platform being longer than the down. In April 1886 approval was given for ‘station alterations’ at Fulbourne, the cost being £270, and these alterations included the building of waiting rooms and the provision of toilets. The up platform had a small brick building with a flat canopy supported on three decorated cast iron brackets on columns. It had a fretted valance which stretched the full width of the platform. The building comprised two rooms, a waiting room and a ladies’ room. Further east along the platform there was a brick gents’ toilet. The down platform was provided with an open-fronted timber shelter with a slightly sloping narrower canopy. The shelter was divided into three bays; two had seating while the third was for storing barrows. There was a barrow crossing between the platform and the level crossing. The original booking office on the other side of the crossing, with its ticket window and porch, was retained until closure of the station. With the doubling of the line the station was re-sited to the east side of Hay Road. The new station had two facing platforms, the up platform being longer than the down. In April 1886 approval was given for ‘station alterations’ at Fulbourne, the cost being £270, and these alterations included the building of waiting rooms and the provision of toilets. The up platform had a small brick building with a flat canopy supported on three decorated cast iron brackets on columns. It had a fretted valance which stretched the full width of the platform. The building comprised two rooms, a waiting room and a ladies’ room. Further east along the platform there was a brick gents’ toilet. The down platform was provided with an open-fronted timber shelter with a slightly sloping narrower canopy. The shelter was divided into three bays; two had seating while the third was for storing barrows. There was a barrow crossing between the platform and the level crossing. The original booking office on the other side of the crossing, with its ticket window and porch, was retained until closure of the station.

A rectangular brick building stood opposite the station house on the west side of the level crossing. This might have been part of the original station or it may have been built when the station was resited to the east side of the level crossing. It was known locally as the 'Ladies' waiting room'. In later years it appears to have been used as a permanent way tool store.

The goods yard, which covered nearly two acres, was to the west of Hay Road on the down side. In 1885 this comprised a siding entered by trailing points that ran through a brick goods shed with a loop round the south side of the shed; at its west end the siding split into two. The shed had a canopy on the north side to provide weather protection for goods being loaded onto, or unloaded from, road vehicles. The shed was extended in the late nineteenth century. Coal merchant Staveley Coals stored house coal, steam engine coal and brickyard coal at the yard. There was also a siding on the up side.

During the latter years of the nineteenth century a number of excursions ran from Fulbourne, which included an ‘Excursion to Ipswich and a boat ride to Harwich’ in 1866 and ‘Pantomime in London’ in 1881. Early stationmasters at Fulbourne included Richard Dalley (1881), Richard Hornford (1891) and Ernest Orman in 1901.

In 1940 large concrete silos were constructed to the rear of the down platform. They were built by the War Office as part of their Strategic Food Storage Programme, to hold wartime emergency supplies of wheat and barley. The silos were not initially rail-connected but, after discussions with the LNER in 1942, a trailing siding from the down main line was laid into the works; this split into two sidings embedded in concrete between the silos and the down platform.

Fulbourne goods yard closed 18 April 1966 although a private siding remained in use after that date. Passenger services were withdrawn on 2 January 1967. Within two years some of the platform edge stones and the waiting room canopy had been removed. By 1975 the stationmaster’s house and the down platform shelter had been demolished. Between 1979 and 1982 The Fielding Industrial Estate with several warehouses was laid out on former goods yard. The waiting room on the up platform survived into the 1990s.

The line was singled in 1983, and the signal box was closed and the level crossing automated under the Cambridge resignalling scheme on 8 May that year, and the box was quickly demolished, probably soon after the down track was lifted in October that year. About 400yd of the down main line east of Fulbourne station was retained to give access to the grain silo siding. In 1986, Vogan Limited, part of the Banks Group, took over the silo and refurbished it for continued grain storage – particularly malting barley. The siding remained in use until c1990, the same time as rail traffic ended at the Dower Wood silos at Newmarket. Today Vogan is part of S&B Herba Foods Limited and the plant handles the milling of rice, plus the splitting and polishing of dried peas and lentils for most of the UK supermarkets and food processors. The sidings are still in place as is 400yd of the old down main line which ends at buffers alongside the former down platform. There is no longer a connection with the still-used up line.

Re-opening of the station was proposed by Cambridgeshire County Council in May 2013 as part of an infrastructure plan to deal with projected population growth up to 2050.

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE NEWMARKET RAILWAY

The first proposal for a railway to serve Newmarket came in 1845 when a prospectus for the ‘Newmarket and Chesterford Railway with a branch to Cambridge ‘ was issued in October for a 17½-mile line from half a mile north of Chesterford on the Eastern Counties Railway's London - Cambridge line which opened on 30 July 1845. The proposed line would provide a fast commuter route between Newmarket and the Capital.

The promoters were lucky to obtain the services of engineers Robert Stephenson, who already had an extensive portfolio of new lines, and John Braithwaite, who had been Engineer-in-Chief to the Eastern Counties Railway until May 1843.

The proposed new line quickly received much social and political support including that of John Manners, 5th Duke of Rutland, who owned the Cheveley Park Estate. Cheveley Park is the oldest stud in Newmarket, with evidence that the site has been used for breeding horses since the reign of Athelstan (924–939). While many new railways were constructed primarily to serve industry, the influential Jockey Club was of the opinion that “a railway to Newmarket would not only be a great convenience to parties anxious to participate in the truly British sport of racing but would enable Members of Parliament to superintend a race and run back to London in time for the same night’s debate“. As a result, the Company’s Bill was unopposed and had an easy passage through Parliament, receiving Royal assent on 16 July 1846.

Share capital of £350,000 was authorised with borrowing powers of £116,666. The Act contained a number of unusual clauses including one that forbade the company from taking on board or setting down passengers at Cambridge station or within three miles of the station between 10am and 3pm on Sundays. Any contravention would incur a £5 per person fine payable to Addenbrooke’s Hospital or another charity nominated by the University.

The contract for construction was awarded to the well known railway contractor Thomas Jackson, and the ceremony for the ‘turning of the first sod’ took place at Dullingham on 30 September 1846.

On 11 November 1846 the N & C convened a shareholders’ meeting to approve an agreement with the Eastern Counties Railway to lease the main line between Newmarket and Chesterford and the Cambridge branch upon completion. Following objections from the Eastern Counties this was not approved and, as a reprisal, the N & C proposed a line from Chesterford to make a connection with the Great Northern Railway (under construction at that time) at Royston. This would have provided and independent route into East Anglia using connections with the Norfolk Railway at Thetford, and the Eastern Union Railway at Bury St Edmunds.

In June 1847 the Company obtained Acts to extend its line to Bury with a branch to Ely and to Thetford, which would have provided a new through route to Norwich with a connection to the Norfolk Railway which ran from Brandon to Norwich and Yarmouth. None of the lines were built at this time due in part to friction between the Eastern Counties and the Norfolk Railway, with the Newmarket & Chesterford Railway becoming a pawn in the acrimonious negotiations between the two larger companies.

While these complex ‘games’ were being played out, construction of the twin-track line proceeded rapidly, and in 1847 the Newmarket & Chesterford Railway changed its name to the Newmarket Railway.

Further unsuccessful negotiations with the Eastern Counties Railway to lease or amalgamate with Newmarket Railway took place in February 1848. Following this failure to reach an agreement, the Newmarket Company approached the Norfolk Railway who agreed to transfer the proposed Thetford – Newmarket route to them. This proposal would have diverted around £40,000 worth of traffic away from the ECR onto the Newmarket Railway but, before an agreement was reached, the ECR changed its mind and approached the Newmarket Company with a new proposal. An agreement was reached on 27 March allowing the ECR to take over the management of the line. As a result, the Newmarket Company deferred its agreement with the Norfolk Railway and abandoned its own scheme to extend its main line south-west to Royston. As part of their agreement, the ECR would provide funds to liquidate the liabilities of the Newmarket Railway and to complete the Cambridge branch. Newmarket shareholders would receive a guaranteed dividend of 3 per cent for two years and, thereafter, 3 per cent.

On 3 January 1848 the Newmarket Railway opened its main line to goods traffic, opening fully on 4 April 1848, with intermediate stations (from south to north) at Bourn(e) Bridge, Balsham Road, Westley (later renamed Six Mile Bottom) and Dullingham. The rolling stock included six tender locomotives (Twelve were ordered but only six were delivered, the remainder going to the Stockton & Darlington Railway). built by Gilkes, Wilson and Company of Middlesbrough, first class, second class and third class carriages, luggage vans and horse boxes. The Company timetable for August 1848 shows four passenger trains on weekdays in each direction with two on Sundays. At that time passengers wishing to continue to Bury St Edmunds had to travel by horse and carriage from Newmarket. The result of the three months up to 30 June 1848, showed that the total traffic receipts were £3,085 7s 7d and the running expenses £2,059 5s 7d, showing a balance of £1,026 2s Od. The Newmarket Company ran its own line for only ten months with the ECR taking control of the management on 2 October 1848. This agreement still, however, had to be approved by ECR shareholders.

By this time the fortunes of ‘Railway King’ George Hudson had begun to decline. Hudson had been appointed Chairman of the ailing Eastern Counties Railway in 1845. He was interested in the ECR as he felt it offered an opportunity for an alternative route from York to London, although the truth was the ECR had an appalling reputation for time-keeping and safety at this time. Hudson immediately ordered the payment of a generous dividend for the shareholders.

In 1848 a pamphlet called ‘The bubble of the age’ or ‘The fallacy of railway investment, Railway Accounts and Railway dividends’ alleged that the dividend of Hudson’s companies was paid out of capital rather than revenue. Hudson had been borrowing money at a high interest rate to keep some of his companies afloat, and many of these companies were left in a difficult position with falling revenues in an economic depression and little scope for future shareholder dividends. By October 1848 it seemed doubtful whether the disgruntled ECR shareholders would approve the agreement with the Newmarket Railway. At the ECR’s Annual General Meeting on 28 February 1849 Hudson and his Directors decided not to put the confirmation of the agreement before the shareholders. Hudson decided not to attend to face the wrath of the shareholders, and within a short time he was forced to resign and the agreement with the Newmarket Railway was scuppered. In 1848 a pamphlet called ‘The bubble of the age’ or ‘The fallacy of railway investment, Railway Accounts and Railway dividends’ alleged that the dividend of Hudson’s companies was paid out of capital rather than revenue. Hudson had been borrowing money at a high interest rate to keep some of his companies afloat, and many of these companies were left in a difficult position with falling revenues in an economic depression and little scope for future shareholder dividends. By October 1848 it seemed doubtful whether the disgruntled ECR shareholders would approve the agreement with the Newmarket Railway. At the ECR’s Annual General Meeting on 28 February 1849 Hudson and his Directors decided not to put the confirmation of the agreement before the shareholders. Hudson decided not to attend to face the wrath of the shareholders, and within a short time he was forced to resign and the agreement with the Newmarket Railway was scuppered.

Having taken over control of the line without the agreement of its shareholders the ECR did its best to force the Newmarket Railway out of business by forcing exorbitant running costs on the company. The ECR introduced a charge of 1s 5d a mile for locomotives, much in excess of the normal rate elsewhere, and it also charged the Newmarket Railway £600 a year for the management or rather, as the Chairman of the Newmarket Railway had no hesitation in calling it, the ‘mismanagement’ of the line.

During the three months to 4 January 1849 the Newmarket Company made a profit of only £704, out of which they had to pay bond interest of £2,000, a problem rendered all the more difficult because the Eastern Counties Railway held on to even this small balance on the grounds of alleged other claims; in addition the Newmarket Company had to defray out of capital the cost of maintaining the permanent way and stations.

On 22 March 1849 a committee was set up to look into the affairs of the company. The committee was chaired by Cecil Fane, a Commissioner in Bankruptcy. In his report presented on 14 May 1849 Fane was of the opinion that the only way of saving the company was to construct the Cambridge branch.

The Newmarket Railway considered regaining control of the line and approaching contractor Thomas Jackson to take over the operation; nothing came of this or a further appeal to the Eastern Counties Railway for more lenient terms. Without funds to pay Jackson to build the Cambridge branch it was soon clear that the only option was to close the line which was quickly effected without consulting the shareholders. The line closed to all traffic on 30 June 1850 just 2½ years after it opened, and Newmarket lost its rail connection. The ECR took all the company’s rolling stock in lieu of existing debts.

With no income, and mounting debts, the company had no option other than to go into administration under the control of Commissioner Fane who soon made it clear that he was unimpressed by the manner in which the directors had closed the line without calling a shareholders’ meeting. He criticised the decision to build the line from Chesterford (a small village) rather than Cambridge (a large town) and reprimanded the Board for mishandling negotiations with the Norfolk and Eastern Counties Railways. A meeting of shareholders was eventually called on 27 July 1850 at which the existing Newmarket board was replaced by Cecil Fane and a new board of Directors.

The line was reopened between Newmarket and Chesterford on 9 September 1850 using rolling stock borrowed from the Eastern Counties Railway. G W Brown was appointed Manager, and he was quickly able to increase revenue and reduce running costs. All outstanding debts were renegotiated and settled amicably, and Fane was even able to convince the ECR to permit trains to run into its station at Cambridge, avoiding the unnecessary expense of a separate station. Under the Eastern Counties and Newmarket Railways Arrangements Act 1852 the ECR agreed that in any year after the opening of the Cambridge branch in which the revenue was insufficient to pay a dividend of 3 per cent on the Newmarket Company’s capital of £350,000, the Eastern Counties Railway would make it good up to not exceeding £5000 in any one year. In the first year of operations this agreement cost the ECR £3,705 9s 7d.

At this point it’s worth mentioning that some strange discrepancies appeared in the track mileages which ‘moved’ Dullingham and Six Mile Bottom stations much closer to Newmarket. Although technically this would mean a loss of revenue at the Newmarket end of the line, it had the knock-on effect of increasing mileages from Newmarket, Dullingham and Six Mile Bottom to the Chesterford section stations. This may account for the high fares applied to the latter section during the course of its existence, thus hastening its demise. However, although skulduggery is suspected it is not known if this was indeed the case. The suspect mileages appear in a number of surviving Bradshaw’s Guides but, significantly, not until the ECR had taken over operation of the line.

In 1851 the ECR published a guide aimed at promoting their routes and the places they served. The entry for the Newmarket & Chesterford would do little to attract custom. 'The line is sixteen miles long; and, as a pecuniary speculation, has been a most unfortunate one. It was constructed by an independent Company, but is now worked by the Eastern Counties. Chesterford we have already noticed; and between that place and Newmarket, there is little worth attention.'

Having settled the debts owed to Thomas Jackson the contractor agreed to finish the line at a cost not exceeding £9,000. Cecil Fane had an ingenious plan for financing the construction costs. As built, the Chesterford – Cambridge line was double track, but it was clear that the volume of traffic that would be handled by the line once the Cambridge branch was opened could easily be accommodated on a single line with passing places. On the southern section of the line one set of rails and sleepers were lifted, and these provided 11 miles of track and sleepers which could be used for the Cambridge branch, far in excess of what was needed.

Construction of the single-track branch was far from plain sailing as the connection with the Eastern Counties Railway at Cambridge proved problematic. The plans approved by Parliament showed a curve at the junction with a radius of 20 chains but, owing to circumstances beyond the control of the company, it was necessary to realign the curve to one with a radius of only 8 chains. This deviation required the consent of the Commissioners of Railways but was turned down as the company’s powers of compulsory purchase had expired and the approval of the landowners involved had not been received. The impasse was eventually resolved and the line was completed. An inspection place on 7 October 1851 and, with approval now received, the Cambridge branch opened to all traffic on 9 October 1851. Construction of the single-track branch was far from plain sailing as the connection with the Eastern Counties Railway at Cambridge proved problematic. The plans approved by Parliament showed a curve at the junction with a radius of 20 chains but, owing to circumstances beyond the control of the company, it was necessary to realign the curve to one with a radius of only 8 chains. This deviation required the consent of the Commissioners of Railways but was turned down as the company’s powers of compulsory purchase had expired and the approval of the landowners involved had not been received. The impasse was eventually resolved and the line was completed. An inspection place on 7 October 1851 and, with approval now received, the Cambridge branch opened to all traffic on 9 October 1851.

By this time it was clear that the Chesterford line would never be profitable so it closed permanently on 9 October 1851, coinciding with the opening of the Cambridge branch; the service from Newmarket was diverted onto the new branch from that date despite the distance between London and Newmarket increasing by 7½ miles. The last timetable issued in August 1851 showed three trains in each direction and no Sunday service. Trains stopped at the intermediate stations only by request. Two intermediate stations on the Cambridge branch were provided at Cherry Hinton and Fulbourne. Neither of these was ready for the opening of the line and they did not appear in Bradshaw until August 1852. Cherry Hinton station was very short-lived closing permanently in March 1854.

The new line was an immediate success and quickly revived the fortunes of the company. Four months later the Company declared a dividend of 1s 6d with a further dividend of 5s 0d being paid the following August: a paltry return on a £25 share, but considering that the company had just come out of bankruptcy it was a promising rebirth.

An Act of 1852 authorised the Eastern Counties Railway to purchase the Newmarket Company at any time. It exercised this right and took over the Newmarket Company’s bond debt of £116,666, and by 30 June 1854 had paid off the debentures of £210,000 in cash which they had issued in purchase of the Newmarket Company’s lines. They thus paid £326,923 for 13 miles of line between Cambridge and Newmarket and included the redundant track between Six Mile Bottom and Great Chesterford which was not officially abandoned until 1858. The ECR timetable for 1853 shows three trains in each direction on weekdays, with trains stopping at the four intermediate stations only by request. The ECR minutes for 10 August 1854 record that the line of the route from Six Mile Bottom is to be abandoned and the land offered to the original owners. An ECR working timetable from September 1856, five years after the southern section of the Newmarket Railway closed but two years before the Act of Abandonment, confirms there was no goods traffic over the old line, and it is likely there was no traffic of any kind after 1851. The minutes of the ECR make reference to ‘Chesterford Junction’ at least as late as 1856 but not of the junction at Six Mile Bottom after the 1851 closure. This suggests the junction at Six Mile Bottom was removed but the remaining single track remained connected at Chesterford, probably until after the Abandonment Act which was passed on 8 July 1858.

N & C Fares

Newmarket - London |

1st class |

2nd class |

3rd Class |

Parly |

| August 1848 |

14/2 |

10/6 |

6/6 |

5/5½ |

| March 1850 |

15/- |

11/- |

7/- |

5/5½ |

| May 1851 |

15/6 |

11/6 |

7/6 |

5/5½ |

Between 1852 and 1854 the Newmarket line was extended north to Bury St Edmunds, thereby completing the route to Ipswich. This extension involved tunnelling 1099yd under the Warren Hill training grounds to the north of the 1848 station. When the Bury St Edmunds extension opened on 1 April 1854, trains running into the old terminus then had to reverse out of the station to continue their journey to Bury.

Under an Act of 1862 the Eastern Counties, East Anglian, Newmarket, Eastern Union and Norfolk Railways and about thirty smaller companies amalgamated to form the Great Eastern Railway.

Doubling of the line between Cambridge and Six Mile Bottom was completed in the second half of 1875. When the line from Newmarket to Ely opened on 1 September 1879, bringing additional through traffic, the awkward reversal was avoided by opening a new island platform at a slightly lower level east of the original terminus. The new platform was usually referred to as the ‘Lower’ station. For some years Newmarket was, in effect, two separate stations although they did share a restaurant. The original single upper platform was used by trains from Cambridge terminating at Newmarket while the lower island was used by through trains to Bury and Ely.

On 14 September 1880 GER minutes record a proposed revival of the abandoned line between Chesterford to Six Mile Bottom and an estimate of the cost of land and works was requested. Although a revival of the line was again discussed in 1892 and 1893 it was always deferred and no action was ever taken.

On 21 April 1885 a non-timetabled station called Warren Hill was opened at the north end of Warren Hill Tunnel. This was built to cater for the increasing number of passengers arriving from the east and the north on race days.

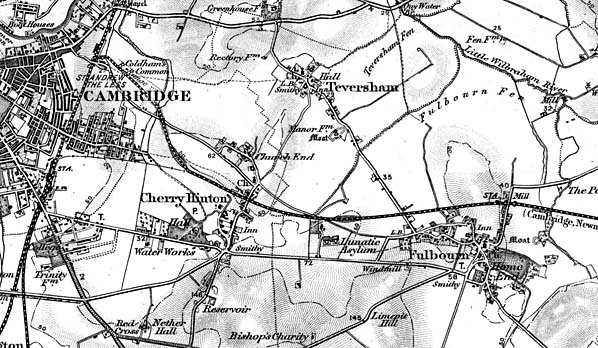

At Cambridge major platform lengthening and remodelling of the main building took place in 1863, and the station layout was altered in 1896 by deviating the Newmarket line approaches with a new alignment curving round to the north of the Romsey Town area of Cambridge to a new junction with the Ely – Cambridge line at Coldham Lane Junction. This avoided the delays caused by the previous difficult crossing of main lines to enter Cambridge station. The old alignment was retained as a siding for carriage storage until at least 1910 but disconnected at Brookfields - the point of commencement of the deviation half a mile west of the former Cherry Hinton station.

Newmarket was home to all the major British racing and training stables which resulted in constant inward/outward traffic in horses going to and coming from race meetings all over the country. Additional horse traffic came from the annual sales at Tattersalls in December and the bloodstock sales which took place at the spring, summer and autumn race meetings. Around the turn of the twentieth century around 12,500 horses were being dealt with annually.

Newmarket station was replaced with a much larger facility half-a-mile south on 7 April 1902. The town’s grand 'New' station opened together with the construction of the access road ‘The Avenue' giving better connections to the town and racecourse. Both were made possible by substantial financial backing from millionaire racehorse owner Colonel Harry McCalmont of Cheveley Park. The new station lacked goods facilities, and the old terminus was retained as the town's goods station and for all horse traffic. It was also used by excursion trains on race days until at least 1954.

During WW1 the railway and goods yard were busy moving troops and armaments. The old terminus building was used as a temporary respite/hospital for wounded soldiers. At the 1923 Grouping the London & North Eastern Railway took control of all the lines around Newmarket, but already there had been a slow decline in rail travel owing to emerging road transport. WW2 was an exceptionally busy period for strategically positioned Newmarket station when traffic increased by 600%. The goods yard proved invaluable for the handling of armaments, including tanks and armoured vehicles as well as thousands of tons of road-making and building material for the many airfields under construction in East Anglia. Race meetings continued throughout the war years and many race specials had to be dealt with in addition to the military traffic. During WW1 the railway and goods yard were busy moving troops and armaments. The old terminus building was used as a temporary respite/hospital for wounded soldiers. At the 1923 Grouping the London & North Eastern Railway took control of all the lines around Newmarket, but already there had been a slow decline in rail travel owing to emerging road transport. WW2 was an exceptionally busy period for strategically positioned Newmarket station when traffic increased by 600%. The goods yard proved invaluable for the handling of armaments, including tanks and armoured vehicles as well as thousands of tons of road-making and building material for the many airfields under construction in East Anglia. Race meetings continued throughout the war years and many race specials had to be dealt with in addition to the military traffic.

Warren Hill station closed in 1945. After the arduous work and neglected maintenance during the war the rail network and rolling stock were in a poor condition; the LNER suffered near-bankruptcy and could not afford the repairs and improvements necessary. 1948 brought Nationalisation with the lines around Newmarket coming under the control of the Eastern Region of British Railways.

Newmarket station remained busy through the 1950s and into the 1960s and the line was never under threat from the Beeching axe. Two of the three remaining intermediate stations, Fulbourne and Six Mile Bottom were, however, closed on 2 January 1967.

Newmarket goods yard closed on 3 April 1967. The line between Cambridge (Coldham Lane Junction) and Chippenham Junction, excepting the section through Warren Hill tunnel which always was single track, was singled between 1980 and 1985 with the exception of a long passing loop at Dullingham, and the station buildings at Newmarket were sold leaving just the north end of the station in use; it had been unstaffed since 2 January 1967. The station is, at the time of writing,served by one train an hour in each direction between Cambridge and Ipswich, with the service operated by Abellio Greater Anglia.

Click here to see a 1904 1:10,560 (6") map showing the original approach to Cambridge station and the 1896 deviation.

Click here to see 14 photos around Cambridge in 1970 by Alan Brown.

Click here to see an animated film of a rail journey between Fulbourne and Cambridge in 1950.

Route map drawn by Alan Young. Bradshaw from Nick Catford. Tickets from Michael Stewart (except 2178 Darren Kitson). Totem from Richard Furness.

Special thanks to Darren Kitson for his research notes. Great Eastern Railway Society for various documents, English Heritage for a free licence to reproduce two photographs and The Newmarket Local History Society for permission to reproduce some text from their web site.

Sources:

See also: Cherry Hinton, Six Mile Bottom, Dullingham, Newmarket (2nd), Newmarket (1st), Balsham Road, Bourne Bridge

See also

Newmarket

Warren Hill

See also special feature: The mystery of Abington Road bridge |

old1.jpg)

old19.jpg)

old2.jpg)

old3.jpg)

old9.jpg)

old10.jpg)

old12.jpg)

1.jpg)

old4.jpg)

old6.jpg)

With the doubling of the line the station was re-sited to the east side of Hay Road. The new station had two facing platforms, the up platform being longer than the down. In April 1886 approval was given for ‘station alterations’ at Fulbourne, the cost being £270, and these alterations included the building of waiting rooms and the provision of toilets. The up platform had a small brick building with a flat canopy supported on three decorated cast iron brackets on columns. It had a fretted valance which stretched the full width of the platform. The building comprised two rooms, a waiting room and a ladies’ room. Further east along the platform there was a brick gents’ toilet. The down platform was provided with an open-fronted timber shelter with a slightly sloping narrower canopy. The shelter was divided into three bays; two had seating while the third was for storing barrows. There was a barrow crossing between the platform and the level crossing. The original booking office on the other side of the crossing, with its ticket window and porch, was retained until closure of the station.

With the doubling of the line the station was re-sited to the east side of Hay Road. The new station had two facing platforms, the up platform being longer than the down. In April 1886 approval was given for ‘station alterations’ at Fulbourne, the cost being £270, and these alterations included the building of waiting rooms and the provision of toilets. The up platform had a small brick building with a flat canopy supported on three decorated cast iron brackets on columns. It had a fretted valance which stretched the full width of the platform. The building comprised two rooms, a waiting room and a ladies’ room. Further east along the platform there was a brick gents’ toilet. The down platform was provided with an open-fronted timber shelter with a slightly sloping narrower canopy. The shelter was divided into three bays; two had seating while the third was for storing barrows. There was a barrow crossing between the platform and the level crossing. The original booking office on the other side of the crossing, with its ticket window and porch, was retained until closure of the station.

In 1848 a pamphlet called ‘The bubble of the age’ or ‘The fallacy of railway investment, Railway Accounts and Railway dividends’ alleged that the dividend of Hudson’s companies was paid out of capital rather than revenue. Hudson had been borrowing money at a high interest rate to keep some of his companies afloat, and many of these companies were left in a difficult position with falling revenues in an economic depression and little scope for future shareholder dividends. By October 1848 it seemed doubtful whether the disgruntled ECR shareholders would approve the agreement with the Newmarket Railway. At the ECR’s Annual General Meeting on 28 February 1849 Hudson and his Directors decided not to put the confirmation of the agreement before the shareholders. Hudson decided not to attend to face the wrath of the shareholders, and within a short time he was forced to resign and the agreement with the Newmarket Railway was scuppered.

In 1848 a pamphlet called ‘The bubble of the age’ or ‘The fallacy of railway investment, Railway Accounts and Railway dividends’ alleged that the dividend of Hudson’s companies was paid out of capital rather than revenue. Hudson had been borrowing money at a high interest rate to keep some of his companies afloat, and many of these companies were left in a difficult position with falling revenues in an economic depression and little scope for future shareholder dividends. By October 1848 it seemed doubtful whether the disgruntled ECR shareholders would approve the agreement with the Newmarket Railway. At the ECR’s Annual General Meeting on 28 February 1849 Hudson and his Directors decided not to put the confirmation of the agreement before the shareholders. Hudson decided not to attend to face the wrath of the shareholders, and within a short time he was forced to resign and the agreement with the Newmarket Railway was scuppered.

Construction of the single-track branch was far from plain sailing as the connection with the Eastern Counties Railway at Cambridge proved problematic. The plans approved by Parliament showed a curve at the junction with a radius of 20 chains but, owing to circumstances beyond the control of the company, it was necessary to realign the curve to one with a radius of only 8 chains. This deviation required the consent of the Commissioners of Railways but was turned down as the company’s powers of compulsory purchase had expired and the approval of the landowners involved had not been received. The impasse was eventually resolved and the line was completed. An inspection place on 7 October 1851 and, with approval now received, the Cambridge branch opened to all traffic on 9 October 1851.

Construction of the single-track branch was far from plain sailing as the connection with the Eastern Counties Railway at Cambridge proved problematic. The plans approved by Parliament showed a curve at the junction with a radius of 20 chains but, owing to circumstances beyond the control of the company, it was necessary to realign the curve to one with a radius of only 8 chains. This deviation required the consent of the Commissioners of Railways but was turned down as the company’s powers of compulsory purchase had expired and the approval of the landowners involved had not been received. The impasse was eventually resolved and the line was completed. An inspection place on 7 October 1851 and, with approval now received, the Cambridge branch opened to all traffic on 9 October 1851. During WW1 the railway and goods yard were busy moving troops and armaments. The old terminus building was used as a temporary respite/hospital for wounded soldiers. At the 1923 Grouping the London & North Eastern Railway took control of all the lines around Newmarket, but already there had been a slow decline in rail travel owing to emerging road transport. WW2 was an exceptionally busy period for strategically positioned Newmarket station when traffic increased by 600%. The goods yard proved invaluable for the handling of armaments, including tanks and armoured vehicles as well as thousands of tons of road-making and building material for the many airfields under construction in East Anglia. Race meetings continued throughout the war years and many race specials had to be dealt with in addition to the military traffic.

During WW1 the railway and goods yard were busy moving troops and armaments. The old terminus building was used as a temporary respite/hospital for wounded soldiers. At the 1923 Grouping the London & North Eastern Railway took control of all the lines around Newmarket, but already there had been a slow decline in rail travel owing to emerging road transport. WW2 was an exceptionally busy period for strategically positioned Newmarket station when traffic increased by 600%. The goods yard proved invaluable for the handling of armaments, including tanks and armoured vehicles as well as thousands of tons of road-making and building material for the many airfields under construction in East Anglia. Race meetings continued throughout the war years and many race specials had to be dealt with in addition to the military traffic.

Home Page

Home Page