A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE COCKERMOUTH KESWICK & PENRITH RAILWAY[Source: Alan Young} This exceptionally scenic route across the northern Lake District came into being principally for the carriage of freight. By 1860 the pig iron and raw ore produced in west Cumberland were required by the steel industries in Durham and Yorkshire. At the same time the available coke ovens were unable to convert coal mined in Cumberland and suitable coal had to be brought there from the Durham coalfield. A two-way traffic thus appeared guaranteed to the promoters of this cross-country railway. A route was already available for these freight movements via Maryport, Carlisle and Newcastle but in 1858, the Eden Valley Railway was authorised from Kirkby Stephen to Penrith. When this and the Stainmore route across the Pennines from County Durham opened, only the 30-mile gap between Penrith and Cockermouth remained to be filled to complete a shorter, more southerly coast-to-coast route.

The Cockermouth & Workington Railway The westernmost link in the cross-country chain was the 8¾-mile Cockermouth & Workington (C&W). Authorised in 1845 and opened on 28 April 1847, this line left the Whitehaven Junction (WJ) Railway at Derwent Junction, ¼-mile north of Workington station. The single line was built economically with 11 wooden bridges which had to be replaced with iron structures in the early 1860s when the opportunity was also taken to widen them in anticipation of a second track being laid. Double track was in use throughout by 1868, the work having been completed by the London & North Western (LNW) railway which absorbed both the C&W and the WJ on 16 July 1866.

The Cockermouth, Keswick & Penrith Railway The company which was to build the 31¼-mile single line from Cockermouth via Keswick to Penrith was incorporated on 1 August 1861. It was quickly decided that the CK&P would not be an operating railway. A subsequent Act of 29 June 1863 provided that passenger and general goods trains would be worked by the LNW and mineral traffic by the Stockton & Darlington as successor to both the South Durham & Lancashire Union (Stainmore) and Eden Valley railways. Soon after, the Stockton & Darlington merged into the North Eastern Railway who in June 1864 obtained powers for the curve between Redhills and Eamont junctions to enable traffic to and from their line to avoid reversal at Penrith.

On 24 October 1864 the CK&P line was inspected by Capt F H Rich for the Board of Trade and the route opened to goods on 26 October 1864. The introduction of passenger trains was not permitted on account of 11 shortcomings notably the inadequate pitching of the railway bank alongside Bassenthwaite Lake and the quality of some abutments, parapet walls, and viaduct structures. Capt Rich visited the line once more on 22 December and was satisfied that the necessary work had been done, enabling the railway to open for passenger traffic on 2 January 1865. The Redhills curve followed on 5 September 1866; the curve was double-track, leaving the CK&P on the north side then passing underneath. Never an operating company, the CK&P retained ownership of the track, stations and signalling until 1923 when the Grouping brought it into the London, Midland & Scottish Railway (LMS). With the demise of the heavy freight traffic in the 1920s, the Redhills Junction to Eamont Junction curve fell into disuse after 1928 though it was not finally abandoned until June 1938. Redhills Junction signal box was then closed and single-line working was introduced between Blencow and Penrith No.1 box.

The CK&P route described Although the company name would suggest that a west-to-east description is logical, most passengers on the line will have travelled from the Penrith end, so a journey along the route will be described.

To avoid high ground east of Penruddock the CK&P made a gradual but complete horseshoe curve to the north between Blencow and Penruddock. Sidings served Flusco Quarry and Harrison's Limeworks. The countryside in this area is gently undulating and given over to pasture. Having passed through Blencow station the line served Flusco Limeworks. The track ran through Andrew's Cutting, excavated into solid rock; this portion of the line was subject to snow drifts and blockages in severe weather.

From Troutbeck Summit there was a short stretch of 1 in 66 down, followed by an easing to 1 in 300 into the station. Whilst the goods yards at Blencow and Penruddock were the usual small country affairs, Troutbeck boasted an array of sidings, and a substantial water tank. The extensive sidings were required for two reasons. First, they provided storage accommodation for heavy trains which had to be worked up the long climb from Threlkeld to Troutbeck in more than one portion. Secondly they could accommodate cattle trucks for the sheep sales held at the auction market, hard by the station. Since the majority of the locomotives had used a considerable amount of their water supply after working up the gradient from Threlkeld, the provision of a water tank of generous size at Troutbeck was essential.

Apart from a short level stretch the gradient continued to fall between Threlkeld and Keswick, as the neighbouring river pursued its course downhill tumbling vigorously over its rock-strewn bed. The 1 in 76 portion was a mile long, ending just before the line emerged from the gorge and passed under the main road eastwards out of Keswick. This was the most substantial station on the line, attractively set adjacent to parkland to the south and with the lofty Skiddaw (3,053ft) dominating the northern horizon.

At the west end of Bassenthwaite Lake station the CK&P crossed the main Keswick - Cockermouth road on the level, the gates being mechanically operated from the signal-cabin. There were only two other level crossings on the line, both being between Bassenthwaite and Embleton, but neither of these was mechanically worked. Although less splendid the scenery through which the line passed to Embleton was still delightful, with the uplands of Thornthwaite Forest to the south and Setmurthy Common to the north. Embleton, the next station, was approached on a rising gradient of 1 in 100. A few hundred yards short of the station a siding served the quarry of the Cumberland Granite Company. Embleton possessed one platform, and there was a small goods yard on the up side, facing Cockermouth, where empty wagons for Close Quarry were often stored.

Passenger train services In 1885, there were five weekday trains in each direction between Workington and Penrith with just one on Sunday. Twenty-five years later in 1910 the number had risen to six on weekdays, but still only one on Sunday. There was an extra train, including one on Sunday, between Workington and Cockermouth. The basic year-round service was supplemented in the height of summer by additional trains including some conveying through carriages further afield. Having previously resisted pressure from the CK&P, the LNW first introduced a through train from Keswick to London during the summer of 1886.

The service was reduced towards the end of the 1914-18 war leaving a basic service of only four trains each way, weekdays only by 1918. Modernisation then closure

All but two of the intermediate stations between Penrith and Workington (Main) were given BR(LM) vitreous enamel nameboards and totems, probably in the late 1950s. Braithwaite (and possibly Brigham) received a new nameboard but no totems. Unfortunately, that was just about the extent of the revolution which accompanied dieselisation. Old thinking continued and by 1959 there were suggestions that the line might be closed because it was losing £50,000 per annum. This was one of a number of BR(LM) lines and individual stations under consideration from closure (Railway Magazine July 1959).

Nothing of significance happened until March 1963 when the ‘Beeching Report’ recommended abandonment of the entire route. All goods facilities were withdrawn with effect from 1 June 1964 except for access to the quarries at Flusco and Blencow. A proposal to withdraw all passenger services was published on 5 July 1963 and followed the usual TUCC procedure. In late December 1966 Barbara Castle became Minister of Transport and one of her early decisions, announced on 10 January 1966, was that the route should close between Workington and Keswick but the remainder of the line to Penrith should be retained in view of the hardship which would be suffered by users of that section. The last trains ran between Keswick and Workington on 16 April 1966 leaving a service of six trains each way between Penrith and Keswick, some of them running from Carlisle. ‘The Lakes Express’ had run for the last time at the end of the previous summer timetable. The last steam-hauled train to travel the entire line between Penrith and Workington was SLS/MLS The Lakes and Fells Railtour on 2 April 1966 hauled by Ivatt Class ‘2’ 2-6-0 locos Nos. 46426 and 46458. The latter loco had the privilege on 22 July 1966 of hauling the Royal Train when HRH the Duke of Edinburgh visited the area.

During 1967, Barbara Castle introduced a ‘white paper’ which proposed, inter alia, to fix the size of the BR network at a level greater than that proposed in the ‘Beeching Report’. Penrith to Keswick was one of a number of lines which were to be retained as ‘basic railways’ whereby costs would be reduced as an alternative to closure. On 4 December 1967, the four remaining signal boxes were closed at Blencow, Penruddock, Threlkeld and Keswick No.1. Except at the two quarries, all points, loops and sidings were taken out of use and the entire branch from Penrith No.1 box (the erstwhile Keswick Junction) to the buffer stop at Keswick station was worked on a ‘one engine in steam’ principle. From 1 July 1968 all five branch stations became unstaffed, no distinction being drawn between the remote intermediate stations and Keswick itself. Most lines which had managed to survive until the end of the 1960s were then able to remain open in what gradually became a less hostile environment. There were, however, a few exceptions and Penrith to Keswick was one of the; also in north-west England, Bury-Rawtenstall, Bolton-Bury-Rochdale, Skipton-Colne and Haltwhistle-Alston were to close. Underpinning Barbara Castle’s plan was a system of line-by-line grants given to ‘uneconomic but socially necessary services’. Political wisdom of the day was that only local passenger services were’ uneconomic’. Freight and long-distance passenger trains had to be self-supporting. So, to cover the losses incurred by BR as a whole, the grant for each subsidised local passenger service had to be set at anything up to ten times the figure previously advanced in favour of closure. Until the system was replaced in 1974, every such line had an artificially high price on its head and each year the Minister found it expedient to reject the odd grant renewal just to show that he was keeping things under control. So in 1969, the Minister announced that the next two-year grant for the Keswick line would be the last unless it survived another passage through the TUCC procedure. Then Peter Walker, Minister of Transport (1970-72) discarded the pleas of hardship which his predecessor had upheld and ordered the line to be closed on 6 March 1972. The remaining freight business at Flusco and Blencow lasted only until 19 June 1972

After closure Talk of preservation soon evaporated when it became clear that the route would be encroached upon very slightly by road improvements with the cost of additional bridge work and other engineering falling on the preservationists and putting the whole enterprise out of reach.

Eden District Council appears not to support the reopening of the Keswick & Penrith Railway and is allowing development at Flusco Business Park to encroach upon the original trackbed. Despite receiving more than sixty objections, Eden District Council's Planning Committee granted planning permission for an industrial unit on the alignment of the Railway at Flusco. The application was made public in April 2009 and the decision was made on 16 July 2009. Officers recommended that planning permission for the industrial unit be granted and did not recommend any conditions regarding protection of the railway trackbed, even though the Council has such policies.

The CKPR PLC has struggled to raise funds and although it has had ‘approval’ of the idea from the Government Regional Growth Fund, local authorities, English Heritage and the National Lottery, no money has come from any organisation. With the money raised, feasibility studies and planning work have already started on route, but as yet nothing has been done in the way of tracklaying. The distance between Keswick and Threlkeld is only 3½ miles, but there are eight bowstring girder bridges which cross the river in this short stretch. The company suffered a massive blow in December 2015 when Storm Desmond caused unprecedented floods which washed away two of the bowstring bridges and a third suffered damage to the base of one abutment which meant that it would be closed to the public until it is deemed safe. Bridge No. 66 (Low Pearson), a dual span bridge east of Briery, was completely destroyed. The masonry pier in the middle of the river was torn apart and the girders carrying the bridge deck ended up as a twisted wreck on the river bed downstream.

In October 2019 the CK&P route appeared in the news regarding the footpath on the Threlkeld to Keswick section. Controversy had arisen regarding the National Park's proposal to approve a tarmacadam surface for the path which was opposed by those who considered this material to be inappropriate for the setting. The outcome of this proposal is awaited. A most encouraging recent development is to be found at Bassenthwaite Lake station. This is the first location along the CK&P where any real signs of revival of the railway are to be found. This extremely attractive site has been purchased with a view to re-laying tracks and restoring the station building. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS BIBLIOGRAPHY

Route map drawn by Alan Young. Totems from Richard Furness. All photos by Maurice Burns unless stated.. To see the

stations on the Cockermouth - Penrith line click on the station name: Cockermouth 1st, Cockermouth 2nd, Embleton, Bassenthwaite Lake, Braithwaite, Keswick, Briery Siding Halt, Threlkeld, Highgate Platform, Troutbeck, Penruddock & Blencow

|

1869 1: 10,560 OS map showing the junction between the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway and the Workington, Keswick and Penritgh Railway south of Penrith station. Click

1869 1: 10,560 OS map showing the junction between the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway and the Workington, Keswick and Penritgh Railway south of Penrith station. Click

Penrith station in Spring 1966. The DMU is about to rasp away to Workington shortly before the line beyond Keswick closed. Jubilee No. 45563 is seen. She was named Australia but on close inspection the nameplate is missing, just the backing plate is present. The loco is generally scruffy and it is not in steam - she is on her way to the scrapyard. She had been withdrawn from Warrington Dallam shed in November 1965 and was scrapped at Cashmore's, Great Bridge (Birmingham) in March 1966 and is clearly taking a circuitous route to the scrapyard via Penrith

Penrith station in Spring 1966. The DMU is about to rasp away to Workington shortly before the line beyond Keswick closed. Jubilee No. 45563 is seen. She was named Australia but on close inspection the nameplate is missing, just the backing plate is present. The loco is generally scruffy and it is not in steam - she is on her way to the scrapyard. She had been withdrawn from Warrington Dallam shed in November 1965 and was scrapped at Cashmore's, Great Bridge (Birmingham) in March 1966 and is clearly taking a circuitous route to the scrapyard via Penrith  At Penrith the CK&P trains started from a covered platform on the down side of the station. At Keswick Junction, 638yd south of Penrith station, the CK&P struck out from the main line and ran parallel to it for a short distance before making a climbing turn to the right and westwards. The gradient soon steepened to 1 in 70. At Redhills, one mile from Keswick Junction the spur of the North Eastern Railway (NER), from Eamont Bridge Junction on the LNW, came in from the up side of the CK&P. This spur was constructed for coke trains from Durham to west Cumberland and loads of haematite iron for smelting and pig iron for shipment from west Cumberland to the east coast works and ports. The NER worked their traffic from Darlington via Barnard Castle, Stainmore Summit and Kirkby Stephen to Eden Valley Junction on the main LNW. line, from whence they had running powers into Penrith. This spur, from Eamont Bridge Junction to the CK&P at Redhills, meant that reversal at Penrith was avoided.

At Penrith the CK&P trains started from a covered platform on the down side of the station. At Keswick Junction, 638yd south of Penrith station, the CK&P struck out from the main line and ran parallel to it for a short distance before making a climbing turn to the right and westwards. The gradient soon steepened to 1 in 70. At Redhills, one mile from Keswick Junction the spur of the North Eastern Railway (NER), from Eamont Bridge Junction on the LNW, came in from the up side of the CK&P. This spur was constructed for coke trains from Durham to west Cumberland and loads of haematite iron for smelting and pig iron for shipment from west Cumberland to the east coast works and ports. The NER worked their traffic from Darlington via Barnard Castle, Stainmore Summit and Kirkby Stephen to Eden Valley Junction on the main LNW. line, from whence they had running powers into Penrith. This spur, from Eamont Bridge Junction to the CK&P at Redhills, meant that reversal at Penrith was avoided. 2F/B 46458 climbs out of Penrith with the Royal Train on 22 July1966.

2F/B 46458 climbs out of Penrith with the Royal Train on 22 July1966. Stephenson Locomotive Society / Manchester Locomotive Society

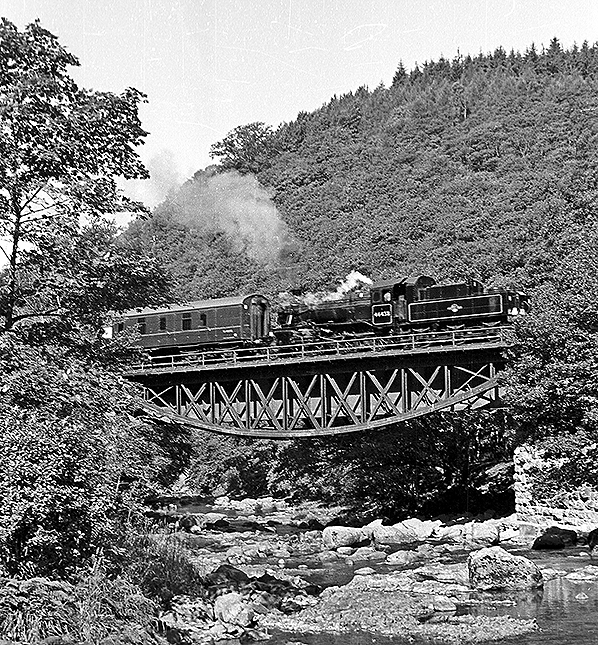

Stephenson Locomotive Society / Manchester Locomotive Society  An LNWR 2-4-2T is seen crossing Briery Bridge east of Keswick early in the twentieth century. The coaches are all 6-wheelers. The first is a Brake and probably a Brake First. The second is a 5-compartment, probably Third. The third is 4-compartment, the fourth is a Luggage Composite and the fifth is a Full Brake.

An LNWR 2-4-2T is seen crossing Briery Bridge east of Keswick early in the twentieth century. The coaches are all 6-wheelers. The first is a Brake and probably a Brake First. The second is a 5-compartment, probably Third. The third is 4-compartment, the fourth is a Luggage Composite and the fifth is a Full Brake. For the first mile westwards from Keswick the line fell on a gradient of 1 in 122 and then ran on the level, or nearly so, over the former marshland between Derwent Water and Bassenthwaite Lake; at one time they formed one continuous lake, but silt deposited by the rivers Greta and Derwent and Newlands Beck gradually accumulated to divide it in two. After crossing Newlands Beck, the single-platform Braithwaite station was entered where there was a small goods yard on the down side and a refuge siding. Either side of the flat valley floor the line was flanked by highland, Skiddaw continuing to dominate the view to the right from the train carriage. Shortly the railway met Bassenthwaite Lake whose shore it hugged for three miles. On this much-photographed stretch of the line, considered by some to be the prettiest in England, passengers could admire the reflection of Skiddaw on the lake to the east while coniferous forest clothed the slopes to the west. Bassenthwaite Lake station was situated among trees just west of the end of the lake. There was a passing loop here and a couple of sidings which handled a fair amount of timber traffic from time to time. Camping coaches were provided here by the LMS and British Railways.

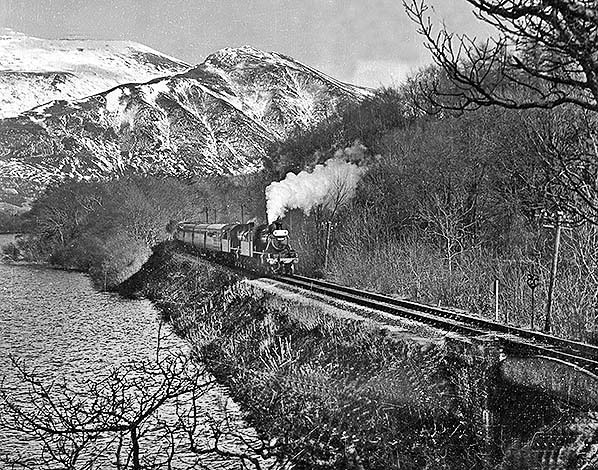

For the first mile westwards from Keswick the line fell on a gradient of 1 in 122 and then ran on the level, or nearly so, over the former marshland between Derwent Water and Bassenthwaite Lake; at one time they formed one continuous lake, but silt deposited by the rivers Greta and Derwent and Newlands Beck gradually accumulated to divide it in two. After crossing Newlands Beck, the single-platform Braithwaite station was entered where there was a small goods yard on the down side and a refuge siding. Either side of the flat valley floor the line was flanked by highland, Skiddaw continuing to dominate the view to the right from the train carriage. Shortly the railway met Bassenthwaite Lake whose shore it hugged for three miles. On this much-photographed stretch of the line, considered by some to be the prettiest in England, passengers could admire the reflection of Skiddaw on the lake to the east while coniferous forest clothed the slopes to the west. Bassenthwaite Lake station was situated among trees just west of the end of the lake. There was a passing loop here and a couple of sidings which handled a fair amount of timber traffic from time to time. Camping coaches were provided here by the LMS and British Railways. 46458 and 46425 skirt Bassenthwaite Lake on 2 April 1966 while Skiddaw rises in the background.

46458 and 46425 skirt Bassenthwaite Lake on 2 April 1966 while Skiddaw rises in the background.

View from train near Troutbeck in April 1966.

View from train near Troutbeck in April 1966. At nationalisation in January 1948 LMS lines in England and Wales were allocated to the new British Railways (BR) London Midland Region (LM). Diesel multiple units first appeared on the Keswick line on 3 January 1955, part of a scheme which also involved the routes from Carlisle to Silloth and to Workington via Maryport. The twin-powered ‘Derby Lightweight’ sets enjoyed some success in attracting additional traffic. They were faster, cleaner and cheaper to operate and offered passengers a much better view. A number of trains started running through to Carlisle. The coming of the diesels prompted the reopening of Blencow station (which had closed in 1952) and the reintroduction of Sunday trains including a through working from Newcastle which was steam-hauled until 1960 and DMU thereafter. Summer Sunday trains operated from 1956 until 1966 inclusive.

At nationalisation in January 1948 LMS lines in England and Wales were allocated to the new British Railways (BR) London Midland Region (LM). Diesel multiple units first appeared on the Keswick line on 3 January 1955, part of a scheme which also involved the routes from Carlisle to Silloth and to Workington via Maryport. The twin-powered ‘Derby Lightweight’ sets enjoyed some success in attracting additional traffic. They were faster, cleaner and cheaper to operate and offered passengers a much better view. A number of trains started running through to Carlisle. The coming of the diesels prompted the reopening of Blencow station (which had closed in 1952) and the reintroduction of Sunday trains including a through working from Newcastle which was steam-hauled until 1960 and DMU thereafter. Summer Sunday trains operated from 1956 until 1966 inclusive.

46458 with the Royal Train near Troutbeck on 22 July 1966.

46458 with the Royal Train near Troutbeck on 22 July 1966. 46458 crosses the River Greta with the Royal Train on 22 July 1966.

46458 crosses the River Greta with the Royal Train on 22 July 1966.

The route through from Keswick station through the Greta Gorge has been turned into ‘The Railway Footpath’; this most scenic stretch can thus be enjoyed on foot. The trackbed is followed almost all the way, including the eight bowstring girder bridges which remain as a memorial to the engineer Thomas Bouch. The footpath rises to pass over the tunnel which has been filled in beneath the point where a large road viaduct goes overhead. West of Keswick, long stretches of trackbed have been superseded by the A66 trunk road including the whole length of Bassenthwaite Lake where the eastbound carriageway occupies the railway alignment.

The route through from Keswick station through the Greta Gorge has been turned into ‘The Railway Footpath’; this most scenic stretch can thus be enjoyed on foot. The trackbed is followed almost all the way, including the eight bowstring girder bridges which remain as a memorial to the engineer Thomas Bouch. The footpath rises to pass over the tunnel which has been filled in beneath the point where a large road viaduct goes overhead. West of Keswick, long stretches of trackbed have been superseded by the A66 trunk road including the whole length of Bassenthwaite Lake where the eastbound carriageway occupies the railway alignment. Type 108 DMU at Threlkeld station on 4 March 1972, two days before closure of the line

Type 108 DMU at Threlkeld station on 4 March 1972, two days before closure of the line 46458 and 46425 crosses Bow bridge on the climb from Keswick on 2 April 1966.

46458 and 46425 crosses Bow bridge on the climb from Keswick on 2 April 1966.

Home Page

Home Page