Notes: The village of Shincliffe at one time possessed two stations. One was the terminus of a branch from Murton and, at its opening in 1839, was the closest station to the city of Durham. This station became Shincliffe Town in 1861 and closed entirely in 1893 when the branch was diverted to a new terminus at Durham Elvet.

The other Shincliffe station, which concerns us here, was on the Newcastle & Darlington Junction route between Ferryhill and Leamside, and it opened in 1844. It was midway between the villages of Shincliffe and Bowburn, each about a mile distant. In 1839 Shincliffe Colliery had opened about half-a-mile north of the station’s site, and a small village developed close to it, but the colliery was to close in 1875.

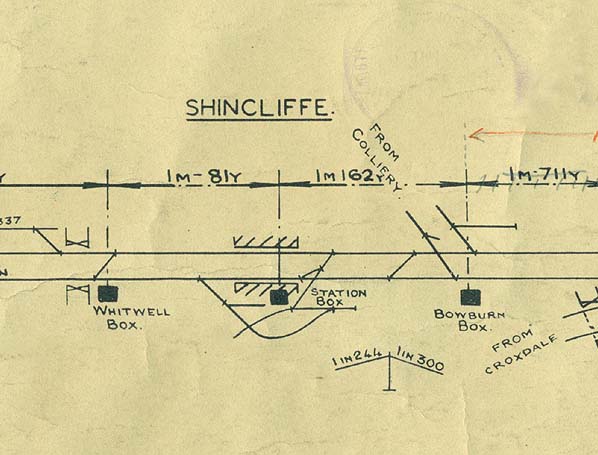

Shincliffe was provided with an attractive station building by G T Andrews, described by Fawcett (2011) as the ‘classic example’ of his work for the N&DJ company. Adjoining the down platform, the building had its axis at right angles to the tracks and was constructed of sandstone blocks, laid in courses, with a ridged slate roof. The distinctive hipped-roof ground floor bay window, favoured by Andrews, faced the platform; when the height of the platform was increased this resulted in the window cill being almost at platform level. An arched porch was centrally placed on the northern elevation. A single-storey extension containing offices stretched south from the two-storey section, and its ridged roof, like that of the two-storey building, had a generous overhang. A signal box stood on the platform immediately south of the passenger buildings, the upper portion cantilevered out so that the platform was not obstructed. A waiting shelter was on the up platform. No footbridge was provided, passengers having to avail themselves of the road overbridge immediately north of the station. Shincliffe was provided with an attractive station building by G T Andrews, described by Fawcett (2011) as the ‘classic example’ of his work for the N&DJ company. Adjoining the down platform, the building had its axis at right angles to the tracks and was constructed of sandstone blocks, laid in courses, with a ridged slate roof. The distinctive hipped-roof ground floor bay window, favoured by Andrews, faced the platform; when the height of the platform was increased this resulted in the window cill being almost at platform level. An arched porch was centrally placed on the northern elevation. A single-storey extension containing offices stretched south from the two-storey section, and its ridged roof, like that of the two-storey building, had a generous overhang. A signal box stood on the platform immediately south of the passenger buildings, the upper portion cantilevered out so that the platform was not obstructed. A waiting shelter was on the up platform. No footbridge was provided, passengers having to avail themselves of the road overbridge immediately north of the station.

The goods facilities were reached by a loop behind the down platform, and the OS 1897 plan indicates that the loop also served Shincliffe sawmill. The 1920 plan no longer names the sawmill. Goods handled in 1913 consisted of 187 tons of potatoes and 34 wagons of livestock. Pedestrian access to the main building was gained by crossing the loop siding.

NER statistics of 1911 indicate that Shincliffe station served a local population of 3,690 and that annual bookings amounted to 17,394 tickets.

During the 1920s bus routes linking the closely spaced villages of the Durham coalfield began to offer stiff competition to railway services. In the case of Shincliffe the demand for public transport was to and from Durham, whose city centre was 2½ miles north- west, whilst the railway provided a north-south service to the distant centres of Newcastle, Sunderland and Darlington. The station stood in a lightly populated area adjacent to the main road to Durham and was inconveniently placed to serve Shincliffe village which was a mile north, and on the way to Durham. As noted above, the colliery close to the station had ceased to operate as early as 1875. The table below shows that in June 1920 the weekday train service offered by the North Eastern Railway was far from frequent. On Sundays a morning and evening train called in each direction.

Up trains June 1920 |

Destination |

Down trains June 1920 |

Destination |

8.09 am |

Middlesbrough |

7.45 am |

Newcastle |

11.26 am |

Middlesbrough |

8.39 am |

Newcastle |

2.35 pm |

Ferryhill |

10.34 am |

Newcastle |

6.05 pm |

Darlington |

2.46 pm |

Newcastle |

9.06 pm |

Ferryhill |

7.23 pm |

Newcastle |

|

|

9.16 pm Sat Only |

Newcastle |

The winter 1937-8 service had decreased to four up and five down weekday trains, with only one morning southbound departure on Sundays. Although the LNER intended to close Shincliffe and neighbouring Sherburn Colliery stations in 1939 passenger services continued until 1941. Goods facilities were retained until November 1963.

For some years the station building was used as a restaurant, trading as the Station House Restaurant until 2007.

BRIEF HISTORY OF 'THE OLD MAIN LINE'

The ‘Old Main Line’ was the name frequently given to the railway between Ferryhill and Pelaw in County Durham which, from 1850 until 1872 formed part of the ‘East Coast’ route from London (Kings Cross) to Newcastle. Prior to 1850 trains ran via Brockley Whins, prior to the opening of the Washington – Pelaw line, and until 1848 terminated at Gateshead rather than Newcastle. From 1872 the present East Coast main line route was used, with diversions in 1906 when the opening of King Edward Bridge removed the need to travel via Gateshead (West) and at Newton Hall Junction, north of Durham, where the curvature of the tracks was reduced in the late 1960s. The evolution of the ‘Old Main Line’ was far from straightforward.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century waggonways were already in existence to move coal from the mines in south-east Northumberland and north-eastern County Durham to tidal water for export. It stands to reason that passengers will have been carried unofficially on such lines, but the first recorded passenger transport by rail in north-east Durham was in 1834 on the Pontop & South Shields route. Originally opened as the Stanhope & Tyne Railroad, it was not established by parliamentary Act but was built on the ‘wayleave’ system under a Deed of Settlement dated 3 February 1834, perhaps to conceal the ambitious nature of the scheme, which was 33¾ miles in length. Under this arrangement the company was to pay a toll, based on the amount of traffic carried, to each landowner through whose property the railway passed.

The south-western end of the line was in Weardale, on the moors just south of Stanhope. Here limestone was quarried, and there were deposits of coal available at intervals between Consett and South Shields. In July 1832 building of the line began, and progress was rapid. Although much of the terrain it crossed was moorland at high altitude, few earthworks were constructed or excavated, and some steep slopes on the south-western section of the route were negotiated with inclines; indeed more than half was worked by inclined planes, either self-acting or with a winding engine, and a few near-level stretches were worked by horses. Locomotives were used only at the eastern end. Much of the line remained unfenced until it closed in the 1960s. The route from Stanhope lime-kilns to Annfield was opened on 15 May 1834, and the eastern section onward to South Shields on 10 September 1834. The engineer T E Harrison surveyed the route; he was to become one of the most influential personnel of the NER.

The carriage of minerals was the priority of the Stanhope & Tyne, and no attempt was made to serve centres of population which would generate passenger traffic. Nevertheless there were requests for passengers to be conveyed so they were permitted to ride free-of-charge on top of the coal wagons. Soon a wagon was attached specifically for passenger use, and shortly afterwards a separate locomotive-hauled passenger coach was provided fortnightly on pay days. Finally, on 16 April 1835, a full passenger service was instated between Durham Turnpike (one mile north of Chester-le-Street) and South Shields, possibly calling from the start at Vigo and Washington. At South Shields a nearby inn sold tickets, and passengers boarded the train in sidings. Part of this route, from Washington to Brockley Whins, was to become a section of the original ‘Old Main Line’. The isolated stretch of passenger railway between Durham Turnpike and South Shields was joined by the Brandling Junction Railway from Gateshead to Brockley Whins, three miles south-west of South Shields, opening to minerals on 30 August 1838 and passengers on 5 September 1839; and the Durham Junction Railway, stretching north from an obscure terminus at Rainton Meadow (with horse-bus connection to Durham) to Washington opened for mineral traffic on 24 August 1838 and passengers on 9 March 1840.

Unfortunately the cost of running the Stanhope & Tyne proved unsustainable. In the moorlands wayleaves cost about £25 per mile per year, but at the eastern end the figures were £300 or more. The outgoings on wayleaves alone amounted to £5,600. Plans for a dock (where Tyne Dock was later opened) were abandoned. Traffic did not develop to the expected levels and the wayleaves proved to be financially crippling. By the close of 1840 the railway company was £440,000 in debt, and it was wound up on 5 February 1841. The following year the Pontop & South Shields Railway obtained an Act to take over the northern end of its track which had hosted the passenger service. The Derwent Iron Company took control of the section south-west of Carr House to bring limestone from Stanhope to its furnaces at Consett. This section later passed into the hands of the S&D.

The Brandling Junction Railway (BJ) originated as a private venture by brothers R W and J Brandling to connect Gateshead, South Shields and Monkwearmouth. The brothers obtained an Act to buy or purchase leases for the land over which their lines would pass, but they chose to proceed by the wayleave system. A company came into being on 7 September 1835 to acquire the assets of the Brandling Railway, and as the Brandling Junction Railway Company it was incorporated by Act of Parliament on 7 June 1836. The Stanhope & Tyne also sponsored a Gateshead, South Shields & Monkwearmouth Railway, but discussions with the BJR resulted in the abandonment of the plan. The BJR opened in three sections. The first was from the Newcastle & Carlisle Railway’s Redheugh in Gateshead, adjacent to the River Tyne, which ascended at 1:23 through Greenes Field to Oakwellgate; this was operated by a stationary engine. A self-acting incline from Gateshead Quayside was opened with it on the same day, 15 January 1839. The route from South Shields to Monkwearmouth opened on 19 June 1839, followed by the connecting lines between Gateshead and Cleadon Lane (later East Boldon) and between Brockley Whins and Green Lane (north-east of Brockley Whins) on 5 September 1839. A chord known as the Newton Garths branch opened on 9 September 1839 between East Boldon and West Boldon junctions, immediately south-east of Pontop Crossing, but this was not used by passenger trains. On 9 March 1840 the west-to-north link between the BJ and S&T opened at Pontop Crossing which enabled through services between the several termini at Gateshead, South Shields, Monkwearmouth and the Durham Junction Railway’s Rainton Meadows to operate. However services from the south had, at first, to reverse from just north of Pontop Crossing to reach Brockley Whins in a complex operation (described on the Brockley Whins page).

The Durham Junction Railway (DJ) was authorised by an Act of 16 June 1834. It became an important link in the chain of railways forming the ‘Old Main Line’, the original intention was merely to redirect to the Tyne coal from the pits in the Houghton-le-Spring area, and from pits served by the Hartlepool Railway. Even these modest ambitions were not realised as its southern terminus was to be at Rainton Meadows, two miles short of Moorsley, its intended destination, and the Houghton-le-Spring branch, authorised by an Act of 1837, was never constructed. Nevertheless a ‘Station Road’ was partly constructed in Houghton – the triumph of hope over reality – which was to be one of the largest population centres in the North-East never to have the benefit of a passenger station.

The DJ’s crowning glory was the stately stone viaduct over the River Wear between Penshaw and Washington, and based upon the Roman bridge at Alcántara, Spain. The last stone was laid on the day of Queen Victoria’s coronation, 28 June 1838, thus it was named Victoria Bridge (or Viaduct). The engineer T E Harrison constructed four main arches, those at each end of 100ft span and the two central arches of 160ft and 144ft; the total length was 811ft and the height above water level was 135ft. In 1843 the DJ became part of the portfolio of the ambitious George Hudson (the ‘Railway King’) as part of his plan for an integrated east-coast route. The Act of 23 May 1844 which confirmed his purchase of the line also made provision for the project of bridging the Tyne.

At Washington the DJ connected with the Stanhope & Tyne whose metals were used as far as Brockley Whins. Here the BJ line was joined, and the passenger service between Rainton Meadows and Gateshead took this route from its inception on 9 March 1840. The S&T owned over half of the DJ shares and also worked the services. As noted above a reversal was necessary at Brockley Whins, and this inconvenience was compounded by congestion caused by the DJ and S&T/P&SS trains sharing the line between Washington and Brockley Whins. To allow more efficient operation powers were sought to construct a direct curve and to widen the line between Washington and Brockley Whins: an Act of 23 May 1844 authorised these projects. The curve was on a difficult site intersected by the River Don and was constructed on a wooden viaduct which stood until 1940. The viaduct was used by main line trains until 1 October 1850 when the more direct route between Washington and Pelaw via Usworth was opened.

For the next stage in the evolution of the ‘Old Main Line’ through County Durham it is necessary to return to the 1830s. The Great North of England Railway obtained its Act for a route from Redheugh Quay at Gateshead to Croft (south of Darlington) on 4 July 1836. After opening from York to Darlington the GNE decided, for financial reasons, not to construct the route onward to Gateshead, and on 5 October 1841 agreed to relinquish the powers to Robert Davies, James Richardson and John Hotham, who acted on behalf of the embryo Newcastle & Darlington Junction Railway. The N&DJ agreed to apply for powers to finish the line and pay all costs. The N&DJ was incorporated on 18 June 1842, and on 11 April 1843 the northern part of the GNE was transferred by Act of Parliament to the N&DJ. Work proceeded swiftly, and the line opened throughout on 15 April 1844 to mineral traffic and to passengers on 19 June. The short section between Belmont Junction (where the Durham branch left the main line) to join the Durham Junction line at Rainton Crossing was the last to be completed. There was now a direct railway link from London to the Tyne: on 18 June 1844, the day before the route opened to regular passenger traffic, a special train made history when it ran from London (Euston Square) to Gateshead in 9h 21m, including stops totalling 70 minutes. At the time of opening the N&DJ did not actually own the line beyond Washington, but had a station at Gateshead, reached via the P&SS and BJ railways: although only authorised by the Act of 23 May 1844 the station was illustrated by an engraving in a Gateshead newspaper four weeks later.

The early days of the N&DJ were difficult owing to strained relations with the GNE. For details see K Hoole’s Regional History vol 4.

The original ‘East Coast’ main line of 1844 therefore ran from Ferryhill to Gateshead via Shincliffe, Leamside, Penshaw, Washington, Brockley Whins and Pelaw. The Gateshead terminus was at Oakwellgate, which had opened on 5 September 1839. On 2 September 1844 Oakwellgate closed, and the service was diverted to the Greenesfield terminus, which had opened on 19 June 1844. This terminus, in turn, gave way to a new through station which would eventually be known as Gateshead East, when the main line was extended to Newcastle Central, crossing the River Tyne on a temporary bridge (opened 1 November 1848) then on the High Level Bridge, which opened on 30 August 1850. From 1 October 1850 the new, shorter route via Usworth was used between Washington and Pelaw, avoiding Brockley Whins. This ‘Old Main Line’ or ‘Leamside’ route was used until 15 January 1872 when through express services were diverted to the route via Durham.

The ‘Old Main Line’ continued life as an important freight route and retained its stopping passenger service between Leamside and Ferryhill into LNER days. This service - latterly amounting to four up and five down trains on weekdays and one up on a Sunday, calling at the intermediate stations of Shincliffe and Sherburn Colliery – was to have been withdrawn in 1939 but closure was deferred until June 1941. Thereafter the Leamside – Ferryhill line was used for passenger trains diverted from the main line via Durham and for freight traffic. In 1991 British Rail mothballed the line, but owing to dumping of rubbish on the lines, removal of rails at level-crossings, theft of 2½ miles of track near Penshaw in 2003, and effects of overall neglect Network Rail decided to close the line entirely and the rails were removed by April 2013. Concrete sleepers recovered from the route are understood to be destined for re-use on the Waverley Route currently under construction between Edinburgh, Galashiels and Tweedbank.

The Durham diversion was, like the development of the Leamside route, a result of evolution rather than one direct action.

BRIEF HISTORY OF 'THE NEW MAIN LINE'

Access to Gateshead from the south was via Leamside until 1872, when the present-day East Coast main line superseded it. However much earlier, in July 1846, the York & Newcastle Railway announced its intention to promote a Bill for a line following a route via the Team valley from Gateshead (and ultimately Newcastle). On 30 June 1848 the Y&N – by now the York, Newcastle & Berwick Railway – obtained an Act authorising construction. The proposed route was from Gateshead via Team Valley to Newton Hall, where a branch to Durham and Bishop Auckland continued southwards, while the main line curved eastwards for about a mile then turned south to join the main line near Belmont Junction. However in 1849 the work was postponed owing to the downfall of George Hudson.

The NER in 1862 revived the project, but the line authorised was only between Gateshead and Newton Hall on the Bishop Auckland branch north of Durham, which had opened from Leamside in 1857. The section eastwards from Newton Hall had been constructed as part of the Bishop Auckland branch, but there was no west-to-south curve near Leamside to allow through running from the north onto the old main line via Shincliffe. Consequently the new line could be used only as an alternative route to Durham and the south via Bishop Auckland; and at first there were only four stopping trains in each direction between Newcastle and Durham. The Team Valley route opened on 1 December 1868, and it became part of the ‘new’ East Coast main line on 15 January 1872 when the line between Relly Mill Junction (one mile south of Durham) and Tursdale Junction (one mile north of Ferryhill) was completed.

Sources and bibliography:

- Biddle, Gordon Victorian stations (David & Charles 1973)

- Biddle, Gordon Britain’s historic railway buildings (Oxford University Press 2003)

- Bragg, S and Scarlett, E North Eastern lines and stations (NERA 1999)

- Clinker, C R Register of closed passenger stations and goods depots

(Avon Anglia 1978)

- Cook, R A and Hoole, K North Eastern Railway historical maps

(RCHS 2nd edition 1991)

- Fawcett, Bill A history of North Eastern Railway architecture (Three volumes)

(NERA 2001-05)

- Fawcett, Bill George Townsend Andrews of York (NERA 2011)

- Guy, Andy Steam and speed: railways of Tyne and Wear from the earliest days

(Tyne Bridge Publishing 2003)

- Hoole, Ken A regional history of the railways of Great Britain: vol 4 The North East

(David & Charles 2nd edition 1974)

- Hoole, Ken Railway stations of the North East (David & Charles 1985)

- Hurst, Geoffrey Register of closed railways 1948-1991(Milepost Publications 1992)

- Quick, Michael Railway passenger stations in Great Britain: a chronology

(RCHS 2009)

- Sinclair, Neil T Railways of Sunderland (Tyne & Wear County Council Museums 1985)

- Teasdale, John G (Ed) A history of British Railways’ North Eastern Region (NERA 2009)

- Young, Alan Lost stations of Northumberland & Durham (Silver Link 2011)

- Hansard Various (HMSO)

- North Eastern Express North Eastern Railway Society (various)

- Darsley, Roger R Darlington - Leamside - Newcastle (Middleton Press 2008)

Ticket from Michael Stewart. Bradshaws from Chris Totty & Nick Catford. Route maps drawn by Alan Young.

To see other stations on the Old Main Line click on the station name: Felling 2nd, Felling 3rd  , Felling 1st, Pelaw 1st, Pelaw 3rd, Pelaw 4th , Felling 1st, Pelaw 1st, Pelaw 3rd, Pelaw 4th  , Pelaw 2nd, Usworth, Washington 2nd, Washington 1st, Penshaw 1st, Penshaw 2nd, Fencehouses, Rainton, Rainton Meadows (on branch), Leamside 1st, Leamside 2nd, Belmont Junction, Durham Gilesgate (on branch), Sherburn Colliery , Pelaw 2nd, Usworth, Washington 2nd, Washington 1st, Penshaw 1st, Penshaw 2nd, Fencehouses, Rainton, Rainton Meadows (on branch), Leamside 1st, Leamside 2nd, Belmont Junction, Durham Gilesgate (on branch), Sherburn Colliery

& Ferryhill

See also Coxhoe (branch from Ferryhill)

See also: Springwell, Brockley Whins (1st site), Brockley Whins (2nd site)

& Boldon (route prior to 1850)

See also Sunderland and Durham (via Leamside):

Durham (still open), Frankland, Cox Green, South Hylton  , Hylton, Pallion 1st, Pallion 2nd , Hylton, Pallion 1st, Pallion 2nd  , Millfield 2nd, Millfield 1st, Millfield 3rd , Millfield 2nd, Millfield 1st, Millfield 3rd  , Sunderland Fawcett Street (on branch) & Sunderland Central (Still open) , Sunderland Fawcett Street (on branch) & Sunderland Central (Still open)

Station still open as part of the Tyne & Wear metro Station still open as part of the Tyne & Wear metro |

old15.jpg)

old12.jpg)

old13.jpg)

old3.jpg)

old14.jpg)

old1.jpg)

12.jpg)

11.jpg)

2.jpg)

10.jpg)

16.jpg)

Shincliffe was provided with an attractive station building by G T Andrews, described by Fawcett (2011) as the ‘classic example’ of his work for the N&DJ company. Adjoining the down platform, the building had its axis at right angles to the tracks and was constructed of sandstone blocks, laid in courses, with a ridged slate roof. The distinctive hipped-roof ground floor bay window, favoured by Andrews, faced the platform; when the height of the platform was increased this resulted in the window cill being almost at platform level. An arched porch was centrally placed on the northern elevation. A single-storey extension containing offices stretched south from the two-storey section, and its ridged roof, like that of the two-storey building, had a generous overhang. A signal box stood on the platform immediately south of the passenger buildings, the upper portion cantilevered out so that the platform was not obstructed. A waiting shelter was on the up platform. No footbridge was provided, passengers having to avail themselves of the road overbridge immediately north of the station.

Shincliffe was provided with an attractive station building by G T Andrews, described by Fawcett (2011) as the ‘classic example’ of his work for the N&DJ company. Adjoining the down platform, the building had its axis at right angles to the tracks and was constructed of sandstone blocks, laid in courses, with a ridged slate roof. The distinctive hipped-roof ground floor bay window, favoured by Andrews, faced the platform; when the height of the platform was increased this resulted in the window cill being almost at platform level. An arched porch was centrally placed on the northern elevation. A single-storey extension containing offices stretched south from the two-storey section, and its ridged roof, like that of the two-storey building, had a generous overhang. A signal box stood on the platform immediately south of the passenger buildings, the upper portion cantilevered out so that the platform was not obstructed. A waiting shelter was on the up platform. No footbridge was provided, passengers having to avail themselves of the road overbridge immediately north of the station.

old2.jpg)

Home Page

Home Page