Notes: There had been numerous proposals for a tunnel under the English Channel throughout the nineteenth Century but the first serious attempt to build a tunnel came with an Act of Parliament in 1875 authorising the Channel Tunnel Company Ltd to start preliminary trials. By 1877 several shafts had been sunk but initial work carried out at St Margaret's Bay, to the east of Dover had to be abandoned due to flooding. In 1880, under the direction of Sir Edward Watkin, Chairman of the South Eastern Railway, a new shaft was sunk at Abbot's Cliff, between Dover and Folkestone with a horizontal gallery being driven along the cliff. This 7ft-diameter pilot tunnel was eventually to be enlarged to standard gauge with a connection to the South Eastern Railway. After Welsh miners had bored 800ft of tunnel a second shaft was sunk at Shakespeare Cliff in February 1881. The site chosen was a platform at the base of the cliff created from the debris from Round Down Cliff which had been blown up by the South Eastern Railway in 1843 during construction of the Folkestone - Dover railway. There were already two railway cottages and a bungalow on the site built by the South Eastern Railway. This tunnel was started under the foreshore heading towards a mid channel meeting with the French pilot tunnel.

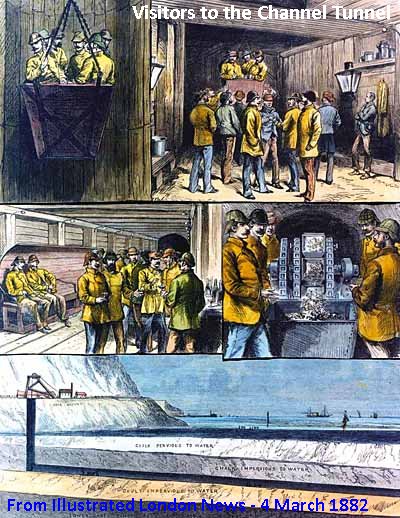

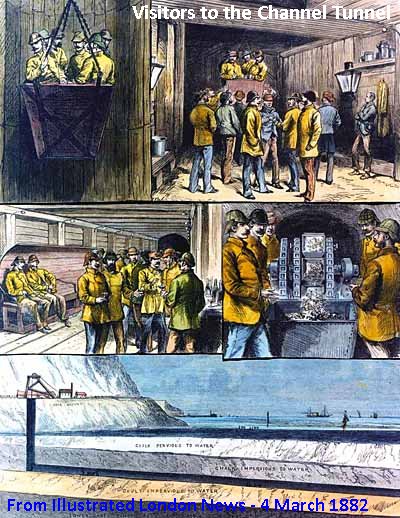

The Channel Tunnel Company expected the pilot tunnel to be completed by 1886, but by 1882 the government was growing anxious about the military implications of a link to Europe and a new military commission was set up to advise on this matter. Sir Edward established a new company, the Submarine Continental Railway Company, which took over the shafts and headings from the South Eastern Railway. To counteract government fear Sir Edward conducted a series of visits to the tunnel, inviting prominent businessmen including the Lord Mayor of London; the visit culminated in luncheon in a chamber cut into the side of the heading.

Visitors to the tunnel were transported by special train from Dover Town station to the Channel Tunnel sidings at Shakespeare Cliff. Considering that there was a large number of visitors, many of them prominent people, it is almost certain that a special platform would have been constructed at the Channel Tunnel sidings to accommodate these invited guests.

Despite Government reservations, tunnel boring continued and, on the British side, it reached a length of 1,250yd in 1882, progressing at a rate of three miles a year. Later visitors to the tunnel included the Prime Minister and Mrs Gladstone, the Prince of Wales and the Archbishop of Canterbury. The Military Commission was concerned that the tunnel would be used for an invasion, and two further Bills submitted to Parliament did not receive their recommendation. Despite Government reservations, tunnel boring continued and, on the British side, it reached a length of 1,250yd in 1882, progressing at a rate of three miles a year. Later visitors to the tunnel included the Prime Minister and Mrs Gladstone, the Prince of Wales and the Archbishop of Canterbury. The Military Commission was concerned that the tunnel would be used for an invasion, and two further Bills submitted to Parliament did not receive their recommendation.

In an attempt to put a stop to the tunnel the Board of Trade invoked Section 77 of the South Eastern Railway Act of 1881 which forbade tunnelling beyond the low water mark. The company agreed to suspend the operation. Watkin informed the Board of Trade that by turning off the machine, which was also responsible for the ventilation in the tunnel, it would be putting the lives of the workforce at risk. The Board of Trade relented and tunnelling continued pending an inspection by the Board’s officials.

Watkin put various obstacles in the way of this inspection and eventually the Board of Trade applied for a High Court order giving them access to the Shakespeare Cliff heading; following this the tunnelling stopped. Following the inspection the Board recommended that the work should cease but Watkin again ignored this request and continued boring the tunnel whenever there were no visitors.

By the end of 1882, the Abbot's Cliff heading had reached 897yd and that at Shakespeare Cliff was 2,040yd in length. The Board of Trade paid a further visit and reported that a further 70yd had been bored in breach of the injunction, as a result of which the Board took out further court proceedings against the company. Following abandonment of the works at the end of 1882 all the plant and buildings were retained on site. By the end of 1882, the Abbot's Cliff heading had reached 897yd and that at Shakespeare Cliff was 2,040yd in length. The Board of Trade paid a further visit and reported that a further 70yd had been bored in breach of the injunction, as a result of which the Board took out further court proceedings against the company. Following abandonment of the works at the end of 1882 all the plant and buildings were retained on site.

In the following years numerous Bills were put before Parliament by the South Eastern Railway, the Submarine Continental Railway and other tunnelling rivals, but all were rejected. This valiant first attempt at building a tunnel under the Channel was dealt its final fatal blow in 1898 when the South Eastern Railway and The Channel Tunnel Co Ltd (which had by this time merged with Submarine Continental Railway Co) were permanently restrained from any further boring beneath the sea bed by the Chancery Division of the High Court. Both shafts were infilled. Although further work on the Channel Tunnel was abandoned, Sir Edward Watkin continued to put pressure on the Government to allow tunnelling to restart. Public visits to the Channel Tunnel site had continued although all work had stopped in 1882; the ticket illustrated here is dated 19 September 1899.

The first suggestion that there might be coal in the area was made in the 1840s and prior to beginning work on the Channel Tunnel, Frederick Beaumont, one of the co-designers of the tunnelling machine, was the secretary of the Kentish Exploration Committee which was established to promote public interest in proving the existence of a concealed coalfield in south-east England. In 1886, the South Eastern Railway Company approached William Boyd Dawkins asking him if his Channel Tunnel work has shown that any coal existed under Kent as this would have brought great financial benefits to the company. Professor Boyd Dawkins enlisted the support of the SER's Chief Engineer, Francis Brady, to persuade Sir Edward Watkin to apply for a Bill to let him search for a viable coal seam below the Channel Tunnel workings. Brady conducted operations and the first borehole was sunk in 1886, striking coal measures in February 1890, at a depth of 1,100ft; and between that depth and 2,274ft, where the boring ceased, 14 seams of coal were encountered. This discovery was regarded as of great national importance for, although some of the upper seams were thin and shalely, lower down the beds seemed richer.

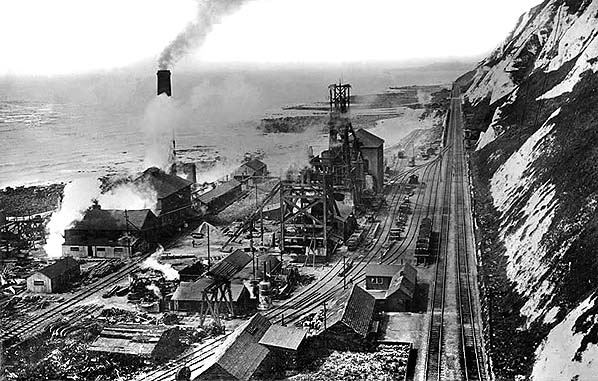

Shareholders of the Channel Tunnel Co refused to exploit the coal, and no efforts to sink shafts were made until 1896 when the Kent Coalfields Syndicate was established by speculator Arthur Burr to take over the freeholds and mineral rights at the old Channel Tunnel workings. The pit was known as Shakespeare or Dover Colliery and was the first of the Kent coal mines.

The sinking of No.1 Pit (Brady) commenced in June 1896, 280ft west of the borehole. Although the earlier borings had indicated the presence of water-bearing rocks, no plans were made to have pumps ready in the event of water ingress. Sinking progressed rapidly but at 366ft water broke in at the shaft bottom, much to the surprise to the shaft sinkers. The shaft filled quickly and it was clear that no further progress could be made without pumps.

To save a delay waiting for pumps to arrive, the sinking of No.2 Pit (Simpson) was started in autumn 1896. On 6 March 1897 water suddenly burst through the shaft floor 'with a force like that of an explosion' and rose rapidly up the shaft. 14 shaft sinkers were working at the shaft bottom: six were hauled to safety but eight drowned. Within 30 minutes the water had risen 80ft and three days later it had risen to 180ft. A management report on 25 March concluded that the men’s candles exploded gas on the surface of the water indicating the presence of firedamp (methane). The editor of the Dover Express opined that coal would never be mined from the pit.

Once the water was pumped out, sinking recommenced although the flooding of the shafts had added to the company's financial difficulties. Work at No.1 Pit again had to be stopped at a depth 520ft, this time owing to running sand; this shaft was later abandoned with no further sinking being undertaken.

An attempt was made to float a new company to take over the syndicate's holdings, with the Kent Collieries Corporation Ltd taking over operations on 6 March 1897.

A third pit (Borehole) to replace the lost Brady shaft was started on the site of Francis Brady's borehole in March 1898. In an attempt to reduce the danger for a further inrush of water a cross heading was driven between the new shaft and Simpson shaft at a depth of 310ft, and pumps were installed there. With this amount of water coming in, the sinking was tedious.

By the end of 1901 work was at a standstill, and the lack of progress resulted in the ousting of the Board of Directors, with the company being taken over by the Anglo-French Consolidated Kent Collieries Corporation Ltd, who undertook to eliminate the water difficulty by the adoption of the Kind-Chaudron method of sinking. This involved lining the shaft with cast-iron tubes (tubbing) as sinking progressed. Although tedious, slow and costly it was successful.

The Kind-Chaudron method carried the pit through the first seam of coal which was disappointingly thin and by 3 February 1905, just 12 tons of coal had been brought to the surface. In an attempt to convince a party of visiting shareholders that the seam was viable they were, misleadingly, shown wagons of coal from Newcastle.

At that stage the French element left the Board of Directors, and a new administration, Kent Collieries Ltd, continued the sinking until August 1905, when No.2 Pit had been carried down to a depth of 1,632ft. This sinking passed through five of the seven 'workable' seams accounted for in the diagrams of Francis Brady's earlier borings. Some of them proved not as thick as the boring indicated, and none was regarded as satisfactory except the last, a two-foot seam, found at 1,600ft, which was described as of 'fair marketable value.' At that stage the French element left the Board of Directors, and a new administration, Kent Collieries Ltd, continued the sinking until August 1905, when No.2 Pit had been carried down to a depth of 1,632ft. This sinking passed through five of the seven 'workable' seams accounted for in the diagrams of Francis Brady's earlier borings. Some of them proved not as thick as the boring indicated, and none was regarded as satisfactory except the last, a two-foot seam, found at 1,600ft, which was described as of 'fair marketable value.'

By the end of 1905 work was concentrated on No.3 Pit, then 650ft deep, bringing it down to the same depth as No.2, with the intention of producing a regular output of coal once the two shafts reached the same depth. By 1907 the colliery was producing about eight tons of coal a day. This still did not represent commercial success as it was less than the colliery itself consumed in its boilers and engines. The colliery was closed in 1909 and placed in the hands of the Receiver. In 1910 the colliery changed hands yet again and production was restarted by the Channel Collieries Trust. By 1912 only 1,000 tons of coal had been raised, still insufficient even to power the colliery's own winding and pumping engines.

All production stopped in 1914 and the colliery finally closed just before Christmas 1915. An announcement was made at the time stating that the mine had been closed owing to the wartime shortage of labour: it never reopened. The colliery shafts were eventually capped by civil engineers Mott, Hay & Anderson. Local ship breakers A O Hill Ltd purchased all the machinery at the colliery (except the main winding engine) in January 1928; the sale included electric engines, pumps, pipes, tanks, small winding engines and 150,000 bricks.

Although Shakespeare Colliery was not financially viable several opened in the area between Canterbury, Sandwich and Dover and were productive until the 1980s.

The first record of miners using the railway to get to the colliery is a working timetable for 1900 which shows early morning trains stopping at Dover Colliery. There was no platform at this time with miners clambering in or out of the trains directly from or onto the track. The South Eastern & Chatham Railway issued tickets to 'Colliery Works Platform' in the first decade of the twentieth century (ticket 8330 above is dated Feb 28 1912). The site of this platform is not known and it may have been a different site from Shakespeare Halt which officially opened on 2 June 1913 for use by miners. The halt consisted of two timber platforms on the main line a short distance to the west of Shakespeare Tunnel, level with Borehole Shaft. Initially passengers had to cross the line using a barrow crossing but in 1914 a footbridge was provided. At this time the SECR restated that the halt was not to be used by women and children.

The halt probably closed with the colliery but was subsequently used by the Admiralty at least from 1920 as well as by railway staff who maintained the line, and by their families who lived nearby in railway cottages. It was also used by visitors and was convenient for Shakespeare signal box and sidings. The footbridge built by the SECR for the miners were removed many years earlier, but there was a small timber shelter (complete with three fire buckets) on the down platform. The up platform never had buildings. The halt was never advertised in any public timetable, and members of the public alighting there would find themselves on an isolated ledge in front of the chalk cliff face. By the 1930s it did, however, appear on Ordnance Survey maps as 'Shakespeare Halt'.

In 1941 Hougham Battery was built close to the cliff-edge between Abbot's Cliff and Shakespeare Cliff, equipped with three 8-inch Mark VIII naval guns and manned by men of 520 Coastal Regiment Royal Artillery. (No 1 gun is seen here) As part of the battery, two coast artillery search light emplacements were built on the colliery site together with engine rooms and accommodation for the searchlight crew. The lights were needed to illuminate and identify ships coming into an area of sea directly below the battery. Other military buildings were erected on the site and the halt saw continuous military use throughout the war. In 1941 Hougham Battery was built close to the cliff-edge between Abbot's Cliff and Shakespeare Cliff, equipped with three 8-inch Mark VIII naval guns and manned by men of 520 Coastal Regiment Royal Artillery. (No 1 gun is seen here) As part of the battery, two coast artillery search light emplacements were built on the colliery site together with engine rooms and accommodation for the searchlight crew. The lights were needed to illuminate and identify ships coming into an area of sea directly below the battery. Other military buildings were erected on the site and the halt saw continuous military use throughout the war.

By the early 1950s most of the wartime buildings had been demolished, although some of the redundant colliery buildings were still standing at this time, including the boiler house, one of the largest buildings on the site. On the cliff top the gun emplacements and many of the adjacent buildings were buried during the construction of the A20 in the 1970s; the battery observation posts can be seen next to the cliff top path and still command a good view over the Channel. The underground Fortress Plotting Room and some other dispersed buildings are also extant.

By the mid 1950s all of the old buildings on the colliery site had been cleared and new sidings were laid across the site. The only buildings remaining were the railway cottages and the signal box, which ensured the continual use of the halt with three trains scheduled to stop there each day if requested; these trains never appeared in public timetables. The halt was also used by the residents living in a number of other isolated dwellings including 'The Cabin' which was sited in front of the sea wall and 'Pascall's Hut' which was further west at the base of the cliff. The Chandler family also lived at the base of the cliff in the 1950s, initially in two bell tents and later in huts. As the platforms were very short anyone wishing to alight at the halt had to find out from the driver which coach to use. The Barnes family, who lived in one of the railway cottages in the 1950s, regularly travelled by train with a pram. This had to be carried in the guard’s van and the guard had to ensure that the trains stopped with the van alongside the platform. Medical staff are recorded as having used the halt in the post-war period, including during the pregnancy of Emmy Barnes when a train had to make an unscheduled stop to bring a doctor. By the late 1960s the halt had been renamed Shakespeare Staff Halt and it received a new green BR Southern Region nameboard on each platform.

In 1955 defence arguments against a Channel Tunnel were accepted as no longer relevant because of the dominance of air power, and both the British and French governments supported technical and geological surveys prior to the construction of a tunnel. A detailed geological survey was carried out in 1964–65. The former colliery site at Shakespeare Cliff was once again selected as ideal for the main construction site, and personnel carrying out preliminary work used the halt between November 1973 and January 1974. Eventually an inclined road tunnel was driven through the cliff, emerging close to the west portal of Shakespeare Tunnel. Construction work commenced on both sides of the Channel in 1974; this was a government-funded project to create twin tunnels on either side of a service tunnel. The tunnels were designed to accommodate car shuttle wagons. In 1955 defence arguments against a Channel Tunnel were accepted as no longer relevant because of the dominance of air power, and both the British and French governments supported technical and geological surveys prior to the construction of a tunnel. A detailed geological survey was carried out in 1964–65. The former colliery site at Shakespeare Cliff was once again selected as ideal for the main construction site, and personnel carrying out preliminary work used the halt between November 1973 and January 1974. Eventually an inclined road tunnel was driven through the cliff, emerging close to the west portal of Shakespeare Tunnel. Construction work commenced on both sides of the Channel in 1974; this was a government-funded project to create twin tunnels on either side of a service tunnel. The tunnels were designed to accommodate car shuttle wagons.

In January 1975, to the dismay of the French partners, the British government cancelled the project. The Labour Party was now in government and there was uncertainty about EEC membership; moreover, cost estimates had doubled and the national economy was troubled. By this time the British tunnel boring machine was ready and the Ministry of Transport was able to perform a 980ft experimental drive before the project was cancelled. In 1976 the halt had lost its nameboards, perhaps indicating lack of use after the cancellation of the tunnel. By 1984 the halt was clearly still in use as it had been fitted with new BR Corporate Identity nameboards with black lettering on a white background. This brought yet another change of name, the nameboards showing that it was now 'Shakespeare Cliff Staff Halt'.

With a change of government in May 1979 the idea of a Channel Tunnel was once again resurrected with a proposal to build a single-track rail tunnel with a service tunnel, but without shuttle terminals. The British government took no interest in funding the project, but Margaret Thatcher, the new Prime Minister, said she had no objection to a privately funded project. In 1981 Thatcher and François Mitterrand, the French president, agreed to set up a working group to look into a privately funded project. In 1985 the engineering, construction, procurement and project management services contract was awarded to Bechtel and a bi-national project consortium called TransManche Link was awarded the construction contract. With a change of government in May 1979 the idea of a Channel Tunnel was once again resurrected with a proposal to build a single-track rail tunnel with a service tunnel, but without shuttle terminals. The British government took no interest in funding the project, but Margaret Thatcher, the new Prime Minister, said she had no objection to a privately funded project. In 1981 Thatcher and François Mitterrand, the French president, agreed to set up a working group to look into a privately funded project. In 1985 the engineering, construction, procurement and project management services contract was awarded to Bechtel and a bi-national project consortium called TransManche Link was awarded the construction contract.

In February 1986, The Treaty of Canterbury was signed allowing the project to proceed. First tunnelling commenced in France in June 1988 with tunnelling underway in the UK in December that year. This short tunnel excavated in 1985 at Shakespeare Cliff was reused as the starting and access point for tunnelling operations on the British side.

The resurrection of the channel tunnel project saw increased use of the halt by construction workers in the early 1990s. The up platform was rebuilt and lengthened and a substantial timber footbridge was built with offices on the bridge. Special season tickets were issued by British Rail for employees of Cross Channel contractors. The resurrection of the channel tunnel project saw increased use of the halt by construction workers in the early 1990s. The up platform was rebuilt and lengthened and a substantial timber footbridge was built with offices on the bridge. Special season tickets were issued by British Rail for employees of Cross Channel contractors.

After considerable discussion, in which around 60 sites were proposed for the disposal of the Channel Tunnel spoil, it was decided that the option with the least adverse environmental impact was to reclaim land at the base of Shakespeare Cliff. There was already access to the site from the Dover to Folkestone railway line and through the tunnel in the cliff left from the 1974 tunnel attempt. The main advantages of this location were that there was no need for any transportation of the spoil to another site, and that a large platform would be created which would serve as a work site as the tunnel was dug.

Extensive research revealed then that depositing spoil at the base of the cliff in artificial lagoons constructed with sheet piled walls was the most environmentally acceptable option. This also had the added advantage of providing an increased work area as tunnelling works progressed. As the tunnel boring machines cut the Chalk Marl it was loaded onto rail tipper wagons, brought back along the tunnel and then moved onto the surface by conveyor belt. 1.7km of sheet piling-enclosed lagoons were then infilled with the Chalk Marl. The area became a 24hr a day work site with 30ha of reclaimed land being created.

The service tunnel broke through under the sea in December 1990, and the Channel Tunnel was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II and President Mitterrand in May 1994. Freight and passenger trains started running in June that year.

Once construction works were completed the Channel Tunnel work site was quickly dismantled, including the footbridge linking the platforms. The site was then landscaped to create an undulating topography including some low lying wetlands. The site opened as the Samphire Hoe Country Park and Nature Reserve on 17 July 1997. The park now attracts around 110,000 visitors per year. Walking, cycling, angling on the sea wall and bird watching are some of the activities available. The park is open between 7am and dusk; admittance is free but there is a charge for car parking. It is ‘wheelchair friendly’ and an education room is available for school use. The site has a walking trail and serves as a wildlife area. Samphire Hoe has been managed by the White Cliffs Countryside Project, in partnership with the owner, Eurotunnel. Once construction works were completed the Channel Tunnel work site was quickly dismantled, including the footbridge linking the platforms. The site was then landscaped to create an undulating topography including some low lying wetlands. The site opened as the Samphire Hoe Country Park and Nature Reserve on 17 July 1997. The park now attracts around 110,000 visitors per year. Walking, cycling, angling on the sea wall and bird watching are some of the activities available. The park is open between 7am and dusk; admittance is free but there is a charge for car parking. It is ‘wheelchair friendly’ and an education room is available for school use. The site has a walking trail and serves as a wildlife area. Samphire Hoe has been managed by the White Cliffs Countryside Project, in partnership with the owner, Eurotunnel.

The halt has fallen into disuse since completion of the Channel Tunnel in 1994 although it has not officially been closed. The timber shelter provided for users on the down platform was still standing in March 2009, albeit in a very dilapidated state. Since then the waiting hut has been demolished and all trace of the up platform has been removed. Today all that can be seen are degraded remains of the down platform complete with the the BR Corporate Identity nameboard, now devoid of its name. The nameboard at the top of the page is from Shakespeare signal box.

Listen to two audio recordings of former residents of the railway cottages at Shakespeare Cliff include their memories of using the railway and the halt.

Hazel and the twins

Den and the tunnel

Click here for a detailed history of Shakespeare Colliery including many photos.

Click here for a detailed history of the first Channel Tunnel attempt in 1880

Click here for 19 pictures of the 1974 Channel Tunnel attempt

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FOLKESTONE - DOVER LINE

The first proposal for a railway between Dover and London was made in May 1834. On 21 June 1836, Parliament passed an Act incorporating the South Eastern & Dover Railway, which shortly afterwards became the South Eastern Railway. The new company was formed to construct the line from London to Dover.

The engineer of the Dover line was William Cubitt who was also engineer of the London & Croydon Railway. The chosen route, which passed over the lines of three other companies, would start at London Bridge, from where it would use London & Greenwich metals as far as Southwark and then turn south towards Croydon. From a junction with the London & Croydon at Norwood the Dover line would then share the London & Brighton main line to Redhill where it would turn east towards Tonbridge, Ashford and Folkestone. Construction began in 1838 at several places simultaneously. The L&BR line to Redhill opened on 12 July 1841. The line between Redhill and Ashford was almost straight with few engineering difficulties. The SER line from Redhill to Tonbridge opened on 26 May 1842, when SER train services began. The line reached Ashford on 1 December 1842 and the outskirts of Folkestone by 28 June 1843. The engineer of the Dover line was William Cubitt who was also engineer of the London & Croydon Railway. The chosen route, which passed over the lines of three other companies, would start at London Bridge, from where it would use London & Greenwich metals as far as Southwark and then turn south towards Croydon. From a junction with the London & Croydon at Norwood the Dover line would then share the London & Brighton main line to Redhill where it would turn east towards Tonbridge, Ashford and Folkestone. Construction began in 1838 at several places simultaneously. The L&BR line to Redhill opened on 12 July 1841. The line between Redhill and Ashford was almost straight with few engineering difficulties. The SER line from Redhill to Tonbridge opened on 26 May 1842, when SER train services began. The line reached Ashford on 1 December 1842 and the outskirts of Folkestone by 28 June 1843.

The route between Folkestone and Dover took the line between the cliff and the sea and a number of major engineering difficulties had to be overcome. It was for this reason that the company bought Folkestone Harbour and turned it into their port of choice for cross-channel ferries. One of the major natural obstacles was the Round Down cliff; the SER's solution was to blow it up! Four tunnels were also required: these were Martello Tunnel (530 yd) at the western end, then Abbotscliffe Tunnel (1 mile 182yd), Shakespeare’s Cliff Tunnel (1392 yd) and finally Archcliffe Tunnel (50 yards - opened out in 1927) at the eastern end near Dover. The Martello tunnel was driven through Gault Clay and Greensand and was more difficult to construct than the other three. Martello and Abbotscliffe are both double-track tunnels. Because of the instability of the Chalk, Shakespeare’s Cliff Tunnel comprised two single-track bores of unusual design. They are very tall, the crown being 28ft above track level, and have Gothic cross-section. Both Shakespeare’s Cliff and Abbotscliffe tunnels are close to the cliff face, so were constructed using horizontal access shafts, as well as the more normal vertical ones. Rubble was taken through the horizontal shafts to be transferred to boats for disposal. Archcliffe Tunnel comprised two short, single bores, passing below Archcliffe Fort on the outskirts of Dover.

The line eventually reached Dover on 27 January 1844. Following the official opening on 6 February the passenger service between London and Dover Town began the following day. Six trains per day were provided in each direction.

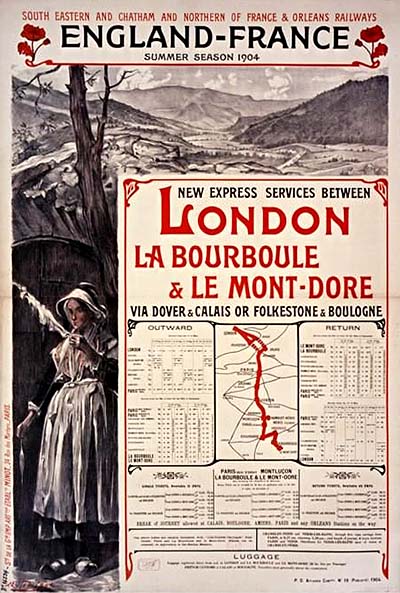

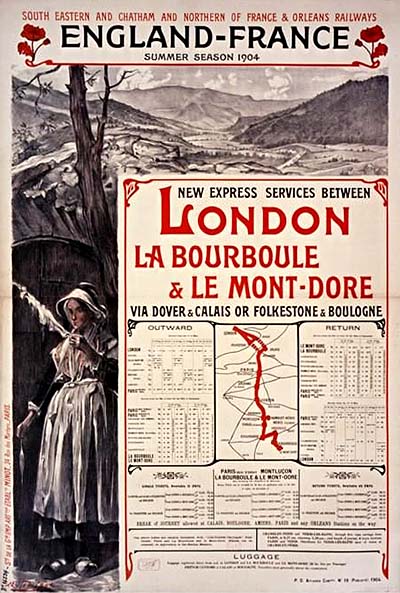

Initially the SER showed interest in attracting tourists to Dover by offering excursion fares. They also introduced ships from Dover to Ostend; but the company’s major interest was the promotion of Folkestone Harbour.

One of the problems that SER constantly faced was that from Folkestone to Dover the tracks were – and still are – so close to the cliffs and sea. The area is known to have been liable to extensive landslips, the first recorded slip having taken place in 1765. On 14 November 1875 there was a severe storm that wrecked groynes and severely damaged the Town station roof, and the track was flooded. Two years later the line was closed for two months due to a 60,000 ton landslide, and it was mooted that SER would not reopen it. Sir Edward Watkin, SER chairman, blamed the rumour on his adversaries at LCDR. He visited the scene of devastation and later arranged for an official reopening after three months’ closure. On Sunday 20 March 1881 the line was again buried under about 20ft of chalk, just west of Abbotscliffe. Eight landslips were recorded before the turn of the twentieth century. One of the problems that SER constantly faced was that from Folkestone to Dover the tracks were – and still are – so close to the cliffs and sea. The area is known to have been liable to extensive landslips, the first recorded slip having taken place in 1765. On 14 November 1875 there was a severe storm that wrecked groynes and severely damaged the Town station roof, and the track was flooded. Two years later the line was closed for two months due to a 60,000 ton landslide, and it was mooted that SER would not reopen it. Sir Edward Watkin, SER chairman, blamed the rumour on his adversaries at LCDR. He visited the scene of devastation and later arranged for an official reopening after three months’ closure. On Sunday 20 March 1881 the line was again buried under about 20ft of chalk, just west of Abbotscliffe. Eight landslips were recorded before the turn of the twentieth century.

On 19 December 1915, a landslide resulted in the entire undercliff supporting the main line moving towards the sea causing approximately 1.9 million cubic yards of chalk to slip or fall completely; the incident blocked a mile of track between the Martello and Abbotscliffe tunnels. The movement occurred over the whole length of the Warren and several cliffs collapsed resulting in the chalk fluidising and burying the rail lines with up to 65ft of debris and creating a flow 230ft out to sea. The maximum displacement was about 165ft near the centre of the disturbance.

Soldiers stationed in the signal box managed to slow the 6.10pm Ashford to Dover service at the mouth of the Martello Tunnel and, although the train came to a halt partly on the landslide derailing some of the coaches, the passengers and crew were able to walk back to Folkestone Junction along the beach and no one was injured. This was one of the largest landslides in Kent.

After consultation with the Board of Trade the SECR decided that the blockage could not be removed during the War. Thus, passengers who wished to travel from Folkestone to Dover were faced with a long, arduous journey as Dover was under military rule and they could not enter the town except by rail. Thus they had to leave Folkestone on the Elham Valley Line to Canterbury then head back to Dover on the old LCDR line. For the remainder of the War the Admiralty used the tunnels to store mines and shells for locally based warships. During the four-year closure, drainage adits were bored from beach level up through the complex in an attempt to halt further coastal erosion, but small landslips continued to occur periodically.

The reopening of the railway between Dover and Folkestone took place on 11 August 1919, the line having been reconstructed during the spring and early summer. SECR became part of Southern Railway that came into operation on 1 January 1923.

Tickets from Michael Stewart except 0011 which is © Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection: Railways 21* (9a). Route map drawn by Alan Young.

Click here to see a film of a train journey between Folkestone Junction and Dover Priory in the 1920s

Sources:

See also: Folkestone (temporary station), Folkestone East, Folkestone Harbour, Folkestone Warren Halt, Archcliffe Junction Staff Halt, Dover Town, Dover Admiralty Pier, Dover Prince of Wales Pier, Dover Marine/Western Docks

& Dover Harbour

See also:

Detailed history of Shakespeare Colliery with many photos.

Detailed history of the first Channel Tunnel attempt in 1880

|

.jpg)

1957 1:2,500 OS map. All the colliery and WW2 buildings have now gone and the mine shafts have been infilled and covered over. A number of new sidings have been laid. The two platforms are still shown but not named. The railway cottages were still occupied at this time but, for some reason, have been omitted from the map.

1957 1:2,500 OS map. All the colliery and WW2 buildings have now gone and the mine shafts have been infilled and covered over. A number of new sidings have been laid. The two platforms are still shown but not named. The railway cottages were still occupied at this time but, for some reason, have been omitted from the map.

Despite Government reservations, tunnel boring continued and, on the British side, it reached a length of 1,250yd in 1882, progressing at a rate of three miles a year. Later visitors to the tunnel included the Prime Minister and Mrs Gladstone, the Prince of Wales and the Archbishop of Canterbury. The Military Commission was concerned that the tunnel would be used for an invasion, and two further Bills submitted to Parliament did not receive their recommendation.

Despite Government reservations, tunnel boring continued and, on the British side, it reached a length of 1,250yd in 1882, progressing at a rate of three miles a year. Later visitors to the tunnel included the Prime Minister and Mrs Gladstone, the Prince of Wales and the Archbishop of Canterbury. The Military Commission was concerned that the tunnel would be used for an invasion, and two further Bills submitted to Parliament did not receive their recommendation. By the end of 1882, the Abbot's Cliff heading had reached 897yd and that at Shakespeare Cliff was 2,040yd in length. The Board of Trade paid a further visit and reported that a further 70yd had been bored in breach of the injunction, as a result of which the Board took out further court proceedings against the company. Following abandonment of the works at the end of 1882 all the plant and buildings were retained on site.

By the end of 1882, the Abbot's Cliff heading had reached 897yd and that at Shakespeare Cliff was 2,040yd in length. The Board of Trade paid a further visit and reported that a further 70yd had been bored in breach of the injunction, as a result of which the Board took out further court proceedings against the company. Following abandonment of the works at the end of 1882 all the plant and buildings were retained on site.

At that stage the French element left the Board of Directors, and a new administration, Kent Collieries Ltd, continued the sinking until August 1905, when No.2 Pit had been carried down to a depth of 1,632ft. This sinking passed through five of the seven 'workable' seams accounted for in the diagrams of Francis Brady's earlier borings. Some of them proved not as thick as the boring indicated, and none was regarded as satisfactory except the last, a two-foot seam, found at 1,600ft, which was described as of 'fair marketable value.'

At that stage the French element left the Board of Directors, and a new administration, Kent Collieries Ltd, continued the sinking until August 1905, when No.2 Pit had been carried down to a depth of 1,632ft. This sinking passed through five of the seven 'workable' seams accounted for in the diagrams of Francis Brady's earlier borings. Some of them proved not as thick as the boring indicated, and none was regarded as satisfactory except the last, a two-foot seam, found at 1,600ft, which was described as of 'fair marketable value.'  In 1941 Hougham Battery was built close to the cliff-edge between Abbot's Cliff and Shakespeare Cliff, equipped with three 8-inch Mark VIII naval guns and manned by men of 520 Coastal Regiment Royal Artillery. (No 1 gun is seen here) As part of the battery, two coast artillery search light emplacements were built on the colliery site together with engine rooms and accommodation for the searchlight crew. The lights were needed to illuminate and identify ships coming into an area of sea directly below the battery. Other military buildings were erected on the site and the halt saw continuous military use throughout the war.

In 1941 Hougham Battery was built close to the cliff-edge between Abbot's Cliff and Shakespeare Cliff, equipped with three 8-inch Mark VIII naval guns and manned by men of 520 Coastal Regiment Royal Artillery. (No 1 gun is seen here) As part of the battery, two coast artillery search light emplacements were built on the colliery site together with engine rooms and accommodation for the searchlight crew. The lights were needed to illuminate and identify ships coming into an area of sea directly below the battery. Other military buildings were erected on the site and the halt saw continuous military use throughout the war. In 1955 defence arguments against a Channel Tunnel were accepted as no longer relevant because of the dominance of air power, and both the British and French governments supported technical and geological surveys prior to the construction of a tunnel. A detailed geological survey was carried out in 1964–65. The former colliery site at Shakespeare Cliff was once again selected as ideal for the main construction site, and personnel carrying out preliminary work used the halt between November 1973 and January 1974. Eventually an inclined road tunnel was driven through the cliff, emerging close to the west portal of Shakespeare Tunnel. Construction work commenced on both sides of the Channel in 1974; this was a government-funded project to create twin tunnels on either side of a service tunnel. The tunnels were designed to accommodate car shuttle wagons.

In 1955 defence arguments against a Channel Tunnel were accepted as no longer relevant because of the dominance of air power, and both the British and French governments supported technical and geological surveys prior to the construction of a tunnel. A detailed geological survey was carried out in 1964–65. The former colliery site at Shakespeare Cliff was once again selected as ideal for the main construction site, and personnel carrying out preliminary work used the halt between November 1973 and January 1974. Eventually an inclined road tunnel was driven through the cliff, emerging close to the west portal of Shakespeare Tunnel. Construction work commenced on both sides of the Channel in 1974; this was a government-funded project to create twin tunnels on either side of a service tunnel. The tunnels were designed to accommodate car shuttle wagons.  With a change of government in May 1979 the idea of a Channel Tunnel was once again resurrected with a proposal to build a single-track rail tunnel with a service tunnel, but without shuttle terminals. The British government took no interest in funding the project, but Margaret Thatcher, the new Prime Minister, said she had no objection to a privately funded project. In 1981 Thatcher and François Mitterrand, the French president, agreed to set up a working group to look into a privately funded project. In 1985 the engineering, construction, procurement and project management services contract was awarded to Bechtel and a bi-national project consortium called TransManche Link was awarded the construction contract.

With a change of government in May 1979 the idea of a Channel Tunnel was once again resurrected with a proposal to build a single-track rail tunnel with a service tunnel, but without shuttle terminals. The British government took no interest in funding the project, but Margaret Thatcher, the new Prime Minister, said she had no objection to a privately funded project. In 1981 Thatcher and François Mitterrand, the French president, agreed to set up a working group to look into a privately funded project. In 1985 the engineering, construction, procurement and project management services contract was awarded to Bechtel and a bi-national project consortium called TransManche Link was awarded the construction contract.  The resurrection of the channel tunnel project saw increased use of the halt by construction workers in the early 1990s. The up platform was rebuilt and lengthened and a substantial timber footbridge was built with offices on the bridge. Special season tickets were issued by British Rail for employees of Cross Channel contractors.

The resurrection of the channel tunnel project saw increased use of the halt by construction workers in the early 1990s. The up platform was rebuilt and lengthened and a substantial timber footbridge was built with offices on the bridge. Special season tickets were issued by British Rail for employees of Cross Channel contractors. Once construction works were completed the Channel Tunnel work site was quickly dismantled, including the footbridge linking the platforms. The site was then landscaped to create an undulating topography including some low lying wetlands. The site opened as the Samphire Hoe Country Park and Nature Reserve on 17 July 1997. The park now attracts around 110,000 visitors per year. Walking, cycling, angling on the sea wall and bird watching are some of the activities available. The park is open between 7am and dusk; admittance is free but there is a charge for car parking. It is ‘wheelchair friendly’ and an education room is available for school use. The site has a walking trail and serves as a wildlife area. Samphire Hoe has been managed by the White Cliffs Countryside Project, in partnership with the owner, Eurotunnel.

Once construction works were completed the Channel Tunnel work site was quickly dismantled, including the footbridge linking the platforms. The site was then landscaped to create an undulating topography including some low lying wetlands. The site opened as the Samphire Hoe Country Park and Nature Reserve on 17 July 1997. The park now attracts around 110,000 visitors per year. Walking, cycling, angling on the sea wall and bird watching are some of the activities available. The park is open between 7am and dusk; admittance is free but there is a charge for car parking. It is ‘wheelchair friendly’ and an education room is available for school use. The site has a walking trail and serves as a wildlife area. Samphire Hoe has been managed by the White Cliffs Countryside Project, in partnership with the owner, Eurotunnel. The engineer of the Dover line was William Cubitt who was also engineer of the London & Croydon Railway. The chosen route, which passed over the lines of three other companies, would start at London Bridge, from where it would use London & Greenwich metals as far as Southwark and then turn south towards Croydon. From a junction with the London & Croydon at Norwood the Dover line would then share the London & Brighton main line to Redhill where it would turn east towards Tonbridge, Ashford and Folkestone. Construction began in 1838 at several places simultaneously. The L&BR line to Redhill opened on 12 July 1841. The line between Redhill and Ashford was almost straight with few engineering difficulties. The SER line from Redhill to Tonbridge opened on 26 May 1842, when SER train services began. The line reached Ashford on 1 December 1842 and the outskirts of Folkestone by 28 June 1843.

The engineer of the Dover line was William Cubitt who was also engineer of the London & Croydon Railway. The chosen route, which passed over the lines of three other companies, would start at London Bridge, from where it would use London & Greenwich metals as far as Southwark and then turn south towards Croydon. From a junction with the London & Croydon at Norwood the Dover line would then share the London & Brighton main line to Redhill where it would turn east towards Tonbridge, Ashford and Folkestone. Construction began in 1838 at several places simultaneously. The L&BR line to Redhill opened on 12 July 1841. The line between Redhill and Ashford was almost straight with few engineering difficulties. The SER line from Redhill to Tonbridge opened on 26 May 1842, when SER train services began. The line reached Ashford on 1 December 1842 and the outskirts of Folkestone by 28 June 1843. One of the problems that SER constantly faced was that from Folkestone to Dover the tracks were – and still are – so close to the cliffs and sea. The area is known to have been liable to extensive landslips, the first recorded slip having taken place in 1765. On 14 November 1875 there was a severe storm that wrecked groynes and severely damaged the Town station roof, and the track was flooded. Two years later the line was closed for two months due to a 60,000 ton landslide, and it was mooted that SER would not reopen it. Sir Edward Watkin, SER chairman, blamed the rumour on his adversaries at LCDR. He visited the scene of devastation and later arranged for an official reopening after three months’ closure. On Sunday 20 March 1881 the line was again buried under about 20ft of chalk, just west of Abbotscliffe. Eight landslips were recorded before the turn of the twentieth century.

One of the problems that SER constantly faced was that from Folkestone to Dover the tracks were – and still are – so close to the cliffs and sea. The area is known to have been liable to extensive landslips, the first recorded slip having taken place in 1765. On 14 November 1875 there was a severe storm that wrecked groynes and severely damaged the Town station roof, and the track was flooded. Two years later the line was closed for two months due to a 60,000 ton landslide, and it was mooted that SER would not reopen it. Sir Edward Watkin, SER chairman, blamed the rumour on his adversaries at LCDR. He visited the scene of devastation and later arranged for an official reopening after three months’ closure. On Sunday 20 March 1881 the line was again buried under about 20ft of chalk, just west of Abbotscliffe. Eight landslips were recorded before the turn of the twentieth century.

Home

Page

Home

Page